A German MP is proposing to halt the FCAS program. Behind this move lies a real risk of implosion for the future European combat aircraft.

Summary

The intervention by German MP Volker Mayer-Lay, who is openly calling for an end to the FCAS program, is not simply a political move. It reveals a deep crisis between Paris, Berlin, and Madrid over the Future Combat Air System, a project estimated to cost more than $100 billion to develop a 6th generation fighter jet and an entire ecosystem of drones and combat cloud technology. The breakdown in trust between Dassault Aviation and Airbus Defence over industrial sharing and control of sensitive technologies is jeopardizing the schedule, which has already been pushed back to 2040. At the same time, the competing Global Combat Air Program (GCAP), led by the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan, is moving forward with a governance structure that is considered more transparent. The call to “finish FCAS” reflects the very real fear among some in German industry of being relegated to the background. Behind the technical debate lies a brutal question: is Europe capable of designing a fighter jet of the future without destroying itself in its internal rivalries?

The FCAS program, a European industrial gamble in open crisis

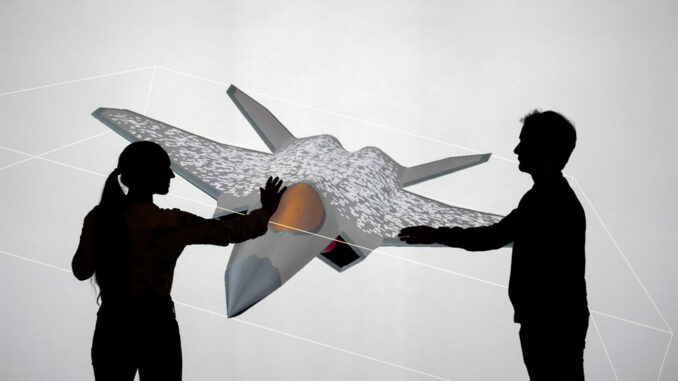

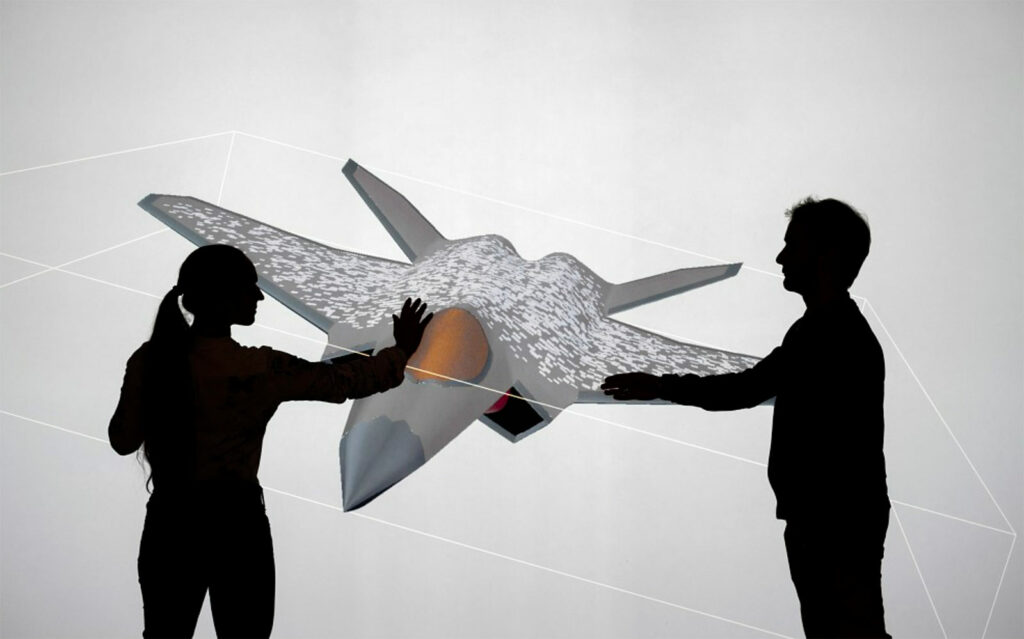

The Future Combat Air System is designed, on paper, to be the pillar of future European air power. The idea is simple: replace the French Rafale and German and Spanish Eurofighters with a 6th generation fighter jet, surrounded by accompanying drones and connected to a “combat cloud” capable of sharing tactical data between platforms in real time. The total cost is estimated at least €100 billion, spread over more than twenty years, with entry into service targeted for around 2040.

In concrete terms, the FCAS is based on a “system of systems.” At its heart is the New Generation Fighter (NGF), theoretically developed under the leadership of Dassault. Surrounding it are Remote Carriers, drones of various sizes, and a combat cloud enabling data fusion, all integrated into existing aircraft. This architecture should offer a major operational advantage: deep penetration capability, multiple sensors, mass effect through drones, and increased resilience in contested environments.

On paper, the equation meets European sovereignty ambitions. In reality, the program is plagued by delays and tensions. Launched in 2017, it has already encountered several political and industrial roadblocks. Technical milestones are being pushed back, negotiations on the next phase are taking months, and public announcements are struggling to mask fundamental disagreements. When a sixth-generation fighter project drifts like this even before the first demonstrator has been built, it is a serious warning sign.

The announced meeting of the French, German, and Spanish defense ministers is expected to decide the immediate future of the program. Officially, everyone remains “committed.” Unofficially, everyone is preparing their backup plans. It is in this context that Volker Mayer-Lay’s statement takes on its full significance.

Volker Mayer-Lay’s attack and German exasperation

CDU MP Volker Mayer-Lay is not a marginal politician. As the Bundestag’s rapporteur for the Luftwaffe, he expresses a strong trend: part of the German political class no longer believes in the FCAS as it is structured today. When he states that “a controlled halt to the program is the only workable solution” and that “Franco-German friendship will survive, but German industry will not survive another delay,” he is putting into words what many in Berlin are saying in hushed tones.

The central argument is straightforward: if the schedule continues to drift, the Luftwaffe will lack capabilities by 2040, and above all, German manufacturers will lose key skills. Germany has already chosen the American F-35 to replace some of its Tornadoes. It is well aware that if the FCAS program fails, the fallback solution will be to buy more American aircraft or, ultimately, to join another program as a junior partner. In this scenario, European technological autonomy is reduced to a slogan.

Mayer-Lay’s criticism is also aimed directly at the French approach. For him, Dassault’s demand to play a dominant role in the NGF amounts to putting Airbus in a subcontractor position. He sees this as an unbearable power imbalance for a country that, with Airbus, has built part of Europe’s industrial power. Implicit in this is a simple accusation: Paris is seeking to lock down technological control, and Berlin refuses to finance a project in which it would be relegated.

The political context also plays a role. With Chancellor Friedrich Merz taking a tougher stance toward Paris, the CDU/CSU is pushing a less conciliatory line than in the Merkel years. The idea that “France is exaggerating” the work entrusted to its manufacturers is echoed in some economic circles. The call to “put an end to FCAS in order to start again on a sound footing” is therefore as much a signal to Paris as it is an internal message to German public opinion: the days when Berlin signed checks without question are over.

The Dassault–Airbus rivalry and the battle for technological leadership

At the heart of the deadlock is the conflict between Dassault Aviation and Airbus Defence. The two groups are not fighting over a few percent of the contract, but over control of a key skill: the design of a highly complex European fighter jet. France believes that Dassault, the direct heir to the Mirage and Rafale, has the expertise to lead the design of a complex fighter jet incorporating stealth, data fusion, and collaborative capabilities. The French manufacturer is demanding real project management control and the ability to make decisions on the aircraft’s architecture.

On the German side, Airbus considers it unacceptable to be confined to peripheral roles when it already has solid experience with the Eurofighter and numerous other major programs. The company is calling for a balanced sharing of not only the volume of working hours, but also design responsibilities. This divergence is crystallized in intellectual property rights, critical interfaces, and the selection of subcontractors. When Mayer-Lay speaks of “subordination,” he is expressing the feeling of downgrading felt by part of the German ecosystem.

The paradox is that some components are progressing rather well. The development of the engine, between Safran and MTU Aero Engines, is often cited as an example of smooth cooperation. But the architecture of the NGF, the symbolic heart of the fighter jet of the future, remains the subject of ongoing wrangling. More seriously, negotiations around a 33% share per country have reportedly been called into question by France’s ambition to obtain around 80% of the work on the airframe and mission system. For German industry, this is a casus belli.

This conflict is not a matter of sensitivity, but of cold calculation. Whoever masters the aircraft architecture and critical software components will control an entire value chain for the next 30 years: modernization, upgrades, exports, derivatives. Accepting a secondary role today means giving up tens of billions of euros in future contracts. In this context, everyone is defending their turf, even if it means undermining the entire FCAS program.

The abandonment scenario and the shadow of the GCAP program

The question posed by Volker Mayer-Lay is brutal: should the FCAS be stopped rather than allowed to get bogged down? Behind this hypothesis lies a very concrete alternative: joining forces with the Global Combat Air Program. This program brings together the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan around a 6th generation fighter called GCAP, sometimes still referred to by its former name, Tempest. The goal is to enter service around 2035, a few years before the FCAS’s stated target.

From an industrial perspective, GCAP has a clearer governance structure, with BAE Systems, Leonardo, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries as its pillars. The overall volume envisaged is around a few hundred aircraft, with a total cost that could exceed €40 to €50 billion depending on the assumptions. Several countries, including Germany, Australia, and Saudi Arabia, are regularly cited as potential candidates for partner or customer status.

If Berlin were to leave the SCAF program to join GCAP, the consequence would be immediate: complete fragmentation of the European effort. We would end up with a Franco-Spanish bloc seeking to salvage a reduced FCAS, a Euro-British bloc around GCAP, and a third pole consisting of countries purchasing F-35s or other American aircraft directly. In other words, Europe would further disperse its resources at a time when the United States and China are investing heavily in their own programs.

Another scenario is circulating: maintaining cooperation on the “combat cloud” and drones, but letting each camp move forward with its own fighter jet. This is the path of an “orderly dismantling” of the FCAS, where the Franco-Spanish NGF would coexist with a possible reoriented German project, or even entry into GCAP. This compromise would save some of the work already undertaken, but would confirm the failure of a truly common European fighter aircraft.

The consequences for the European defense industry and strategic credibility

If the FCAS collapses, the consequences will not be theoretical. On the industrial front, the European value chain will be permanently weakened. Design offices that have worked on concepts for the fighter aircraft of the future will have to reposition themselves. Subcontractors, who have already invested in dedicated capabilities, risk losing part of their order books. In the medium term, we can anticipate forced consolidation, with weaker players being absorbed or relegated to lower-value tasks.

For the armed forces, the impact will be just as concrete. If the FCAS program fails, France, Germany, and Spain will have to significantly extend their current fleets or purchase more American equipment. Extending a Rafale or Eurofighter into the 2050s would require costly successive upgrades, with no certainty that these aircraft would remain relevant in the face of adversaries equipped with advanced stealth capabilities and mass collaborative drones. Purchasing more F-35s would reinforce strategic dependence on Washington, even though official rhetoric about “European strategic autonomy” remains omnipresent.

Politically, the failure of a common European fighter jet would be a heavy blow. It would confirm that Europe is capable of talking about integration, but incapable of practicing it on the most structuring programs. It would also give ammunition to those in several capitals who consider European industrial cooperation to be a trap in which each country seeks to maximize its national income at the expense of the collective project.

Finally, we must look at things without filters: while Paris and Berlin argue over the size of their share of the pie, the United States, China, and Japan are moving forward. Future fighter jet programs cannot be built in small steps. They require quick decisions, clear governance, and a minimum of discipline among partners. If Europeans are not capable of this, they will remain customers, even when they give themselves the illusion of being “co-developers.”

The risk of a European defense system condemned to off-the-shelf purchases

In the longer term, the stakes go far beyond FCAS alone. What is at stake here is Europe’s ability to maintain a coherent defense industrial base. Armament programs structure skilled jobs, research, mastery of strategic components, and the ability to adapt a system to national needs. Giving up on this type of project in favor of off-the-shelf purchases amounts to accepting a gradual loss of skills.

The signs are already visible. Some European countries have placed massive orders for F-35s, sometimes without waiting for the conclusions of discussions on joint programs. Others are looking for quicker solutions to replace aging fleets. The risk is simple: every postponement of the FCAS program makes an additional American purchase more likely. And each American purchase reduces the market available to a future European 6th generation fighter. The program is mechanically weakened, which further reinforces the temptation to abandon it.

In light of this, Volker Mayer-Lay’s call to “cleanly shut down” FCAS may be seen as irresponsible. But he has the merit of asking a question that many are avoiding: is it better to artificially maintain a poorly designed project, or to admit that we need to start again on a radically different basis? For now, the political response remains to save face. Meanwhile, schedules are slipping, costs are rising, and the gap with the major aeronautical powers is widening.

If Europeans want to avoid a future where Future Combat Air System is just another chapter in the long list of failed ambitions, they will have to abandon their posturing and make a clear decision: either accept assumed industrial leadership or build truly shared governance, but stop pretending that the two are compatible.

Sources

Euractiv – German air force MP calls for end to FCAS fighter jet project

Reuters – German, French, Spanish ministers to meet on FCAS

Reuters – France, Germany step up pressure on arms firms over FCAS

Reuters – Merz urges France to stick to deal on joint fighter jet project

Euronews – Is Europe’s mega defense project FCAS in danger of failing?

The Economist – Europe’s biggest military project could collapse

Wikipedia – Future Combat Air System

Wikipedia – Global Combat Air Programme

Meta-Defense – Options for the future of SCAF are taking shape

National Security Journal – Recent analysis articles on FCAS

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.