The SCAF program, intended to replace the Rafale and Eurofighter, is stalling. Contested leadership, industrial differences, and delayed decisions are undermining the European fighter jet.

In summary

The Future Combat Air System (FCAS / SCAF) was supposed to embody European air sovereignty by 2040. Designed to replace the French Rafale and the German and Spanish Eurofighter Typhoon, it promised a sixth-generation fighter integrated into a collaborative combat system. However, on December 16, a government source described the program as now highly unlikely, following further unsuccessful discussions between defense ministers. The core of the problem is neither technological nor budgetary in the short term. It is political and industrial. Behind the rhetoric about European defense, the partners cannot agree on leadership, the distribution of tasks, or even the definition of operational requirements. Structural decisions have been postponed until 2026, a timeline that is incompatible with the goal of entering service in 2040. This delay fuels deep doubt: is SCAF still a credible industrial program or already a political compromise without a clear leader?

The SCAF program and its initial objectives

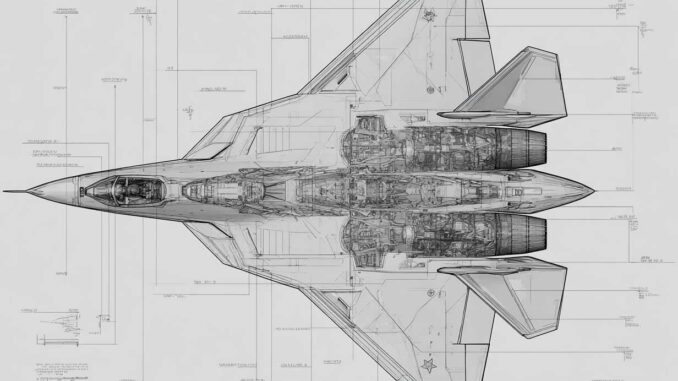

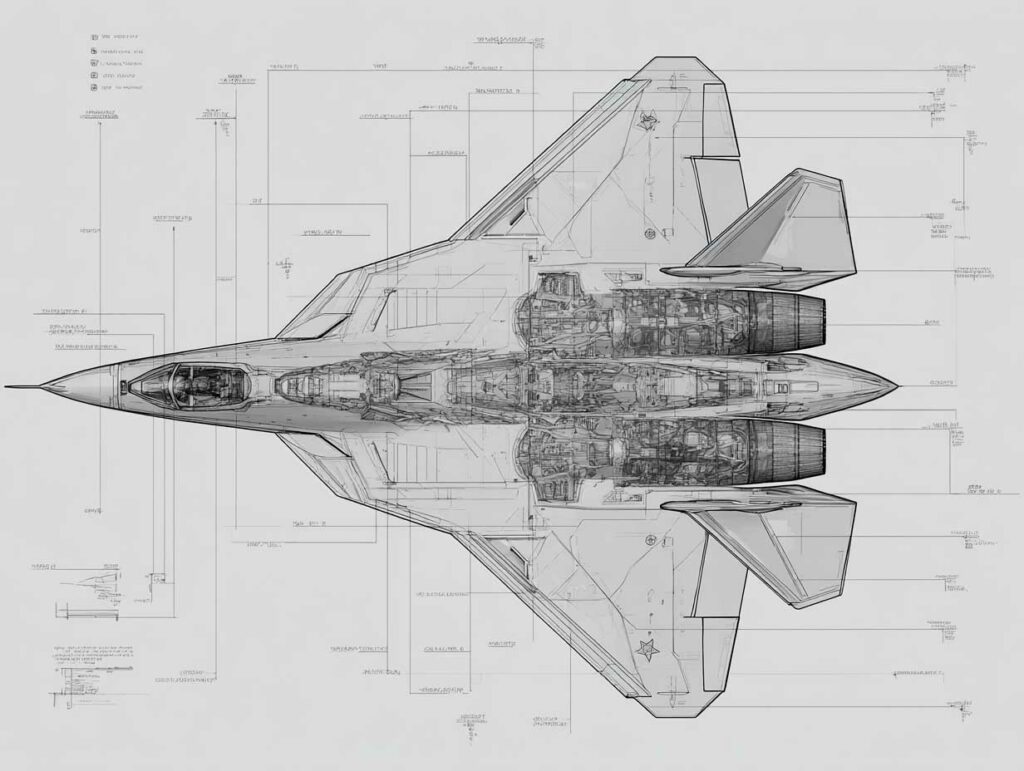

SCAF was officially launched in 2017 by France and Germany, later joined by Spain. The stated ambition is lofty. It is not just a matter of developing a combat aircraft, but a system of systems. The central pillar is the Next Generation Fighter, a new-generation piloted aircraft. It will be supported by accompanying drones, remote sensors, connected effectors, and a combat cloud.

It is scheduled to enter service in 2040, with an initial demonstrator planned for around 2027. The total cost of the program is estimated at between €80 and €100 billion over several decades, including development, production, and support. Each country sees the SCAF as a strategic lever: maintaining industrial skills, strategic autonomy, military credibility, and political weight in Europe.

On paper, the project is coherent. In practice, it quickly comes up against a harsher reality: three countries, three strategic cultures, three major industries, and a single platform supposed to reconcile everything.

Doubts arise after the December discussions

The ministerial discussions in mid-December failed to resolve the fundamental differences. According to a source close to the matter, the program is now considered highly unlikely to continue in its current form. This observation is not new, but it crosses a political threshold.

The sticking points are well known and persistent. They concern governance, industrial distribution, and the definition of military requirements. No lasting compromise has been found despite several years of negotiations. Each round of discussions postpones key decisions without resolving them.

The postponement of fundamental decisions until 2026 is particularly problematic. By that date, the industrial schedule will already be under considerable pressure. Developing a new-generation fighter jet requires at least fifteen years between the definition of requirements and entry into service. Any delay in the design phase automatically results in a postponement of the schedule or a reduction in technical ambitions.

This postponement fuels a growing suspicion that the program is continuing more for political reasons than for rational industrial ones.

Leadership, at the heart of the Franco-German conflict

The issue of industrial leadership is at the heart of the SCAF. France believes that Dassault Aviation, with its experience on the Rafale, should be the prime contractor for the fighter jet. This position is based on facts: the Rafale is a program led from start to finish by Dassault, exported, continuously modernized, and fully operational.

Germany, for its part, refuses to accept French domination over the core of the system. Airbus Defense and Space is claiming an equivalent role, in the name of political and industrial balance. This disagreement goes beyond the simple distribution of tasks. It touches on decision-making capacity, control of critical architectures, and intellectual property.

In reality, a fighter jet cannot be designed by a committee. It requires a chief architect capable of making quick decisions. The lack of clear leadership creates structural inertia. Every choice becomes a subject of political negotiation, when the industry needs quick technical decisions.

This conflict is all the more sensitive because the fighter jet is the pillar around which all the other components of the SCAF are organized. Without agreement on this point, the rest of the program is automatically weakened.

Differences over actual operational requirements

Beyond leadership, the partners do not share the same vision of the future use of the system. France is thinking in terms of expeditionary power. It wants an aircraft capable of operating far away, autonomously, with a strong penetration capability, including in a nuclear environment.

Germany has adopted a more defensive stance, anchored in NATO, with priority given to interoperability and collective defense. Spain is in an intermediate position, with more limited resources and a strong dependence on the choices of its two major partners.

These differences translate into sometimes contradictory requirements in terms of stealth, payload, autonomy, navalization, and nuclear integration. An aircraft cannot do everything without compromise. However, no country wants to be the one to give in.

As a result, specifications are becoming more cumbersome, priorities are diverging, and the risk of a system that is too complex, too expensive, and too late is increasing.

Industrial realities versus political slogans

The political discourse surrounding the SCAF emphasizes European sovereignty and cooperation. These notions are legitimate, but they are not enough to make an aircraft fly. Industry operates according to different rules: risk management, clear responsibilities, and protection of know-how.

Forcing artificial cooperation can produce the opposite of the desired effect. Teams spend more time negotiating than designing. Duplication increases. Costs rise. The schedule slips.

European precedents are illuminating. The Eurofighter Typhoon, born of a compromise between several nations, suffered from delays, cost overruns, and slow progress. Conversely, more centralized programs have shown greater agility.

The SCAF now seems caught in this contradiction: wanting to demonstrate political unity without accepting the industrial constraints that come with it.

The time factor and pressure from alternatives

While the SCAF hesitates, the world is not waiting. The United States is moving forward with NGAD. The United Kingdom is developing Tempest with Italy and Japan. China is investing heavily in its own air combat systems.

Every year of delay widens the gap. For European air forces, the question becomes pragmatic: should they wait for a hypothetical system or invest in available and scalable solutions?

France is modernizing its Rafale to the F4 and then F5 standard, with increased connectivity and collaborative combat capabilities. Germany has ordered F-35s for certain critical missions. These national choices automatically weaken dependence on SCAF.

As credible alternatives emerge, the program loses its indispensable character.

What the current crisis reveals about European defense

The SCAF acts as a revelator. It highlights the structural limitations of European cooperation in the most sensitive areas. Air defense touches on sovereignty, deterrence, and decision-making autonomy. These are subjects on which compromise is difficult.

Europe knows how to cooperate on civilian or support programs. It still struggles to do so on major weapons systems when strategic interests diverge.

The SCAF crisis therefore raises a broader question: does Europe really want strategic autonomy, or just superficial political coordination?

Credible scenarios for the future

Several paths are now plausible. The first is a resizing of the program, with a reduced scope and clarified leadership, at the cost of a political break. The second is a slow continuation, at the risk of the system being obsolete by the time it enters service.

A third, more radical scenario would be to abandon the SCAF altogether in favor of national solutions or more limited cooperation. This option would be politically costly, but industrially coherent.

Whatever the outcome, the time for ambiguity is coming to an end. A fighter jet cannot be decided upon halfway.

The SCAF was supposed to be a symbol of collective power. It is becoming a textbook case of the gap between political will and industrial feasibility. The question is no longer whether it is desirable. It is whether it is still possible without giving up the essentials: a credible, operational system delivered on time.

Sources

FlightGlobal

Reuters

European Defense Industry analyses

Public statements from Dassault Aviation and Airbus Defense and Space

Official communications from French, German, and Spanish defense ministries

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.