The SiVSMD concept revolutionizes military stealth doctrine with autonomous platforms capable of transitioning from air to submarine and using stasis as a weapon of concealment.

In Summary

Military stealth doctrine is undergoing a radical transformation with the SiVSMD (Stand-In Variable Speed Multiple-Domain) concept. This revolutionary approach relies on autonomous platforms capable of transitioning between different environments—air, sea surface, underwater—while exploiting variable speed, including complete stoppage, as a signature reduction technique. In the face of modern integrated defense systems, stealth through radar signature reduction is no longer sufficient. SiVSMD offers discontinuous trajectories where a drone can fly, land on water, dive deep, and then resurface to strike. This multiplicity of domains and speeds creates unprecedented confusion for enemy defenses, which must now simultaneously monitor the sky, the surface, and the seabed with radar, acoustic, infrared, and magnetic sensors. This doctrine marks the transition from passive stealth to active stealth through unpredictability.

The end of traditional stealth in the face of modern defenses

The doctrine of military stealth has long been based on a simple principle: reduce a platform’s radar signature to avoid detection. Fifth-generation aircraft such as the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Lightning II embody this approach, with their angular shapes and radar-absorbing coatings. The F-35, for example, has an estimated radar cross section (RCS) of between 0.001 and 0.005 square meters, equivalent to that of a golf ball.

This strategy is now reaching its limits. Modern integrated air defense systems, such as the Russian S-400 or the Chinese HQ-9, combine several types of radars operating on different frequencies. Low-frequency VHF band radars can detect stealth aircraft at distances of more than 350 kilometers, although the accuracy is still insufficient for missile guidance. This situation creates a paradox: traditional stealth no longer guarantees complete invisibility.

The astronomical costs of these platforms are also problematic. The F-35 program has exceeded $1.7 trillion over its entire life cycle. For a single aircraft shot down, the adversary inflicts a loss of several hundred million dollars. This economic asymmetry favors defense systems, whose unit cost remains much lower.

The SiVSMD concept: stealth through obfuscation and multiplicity

The SiVSMD (Stand-In Variable Speed Multiple-Domain) concept offers a doctrinal break. Developed by Theodoros G. Kostis and published in Joint Force Quarterly in 2025, this model abandons passive stealth in favor of active stealth based on obfuscation. The central idea is simple: instead of merely reducing the signature, we multiply the sources of uncertainty to overwhelm the adversary’s cognitive and technical capabilities.

This doctrine is based on three fundamental pillars. The first pillar is the use of miniaturized, low-cost autonomous platforms, typically drones capable of operating in multiple domains. These systems, with a unit cost of between $50,000 and $500,000, can be deployed in large numbers without risking catastrophic financial losses.

The second pillar is the use of variable speed as a tactical tool. Unlike traditional stealth aircraft, which favor high speed to quickly cross dangerous areas, SiVSMD incorporates phases of slow speed and even complete stoppage. A drone can thus fly quickly to its area of operation, then slow down drastically or land on water to reduce its thermal and acoustic signature.

Third pillar: multi-domain transitions. An amphibious platform can take off, fly at low altitude in “sea-skimming” mode, land on water, then dive underwater before resurfacing for the final attack. This ability to change environments makes its trajectory fundamentally unpredictable.

Discontinuous trajectories: from air to water and back again

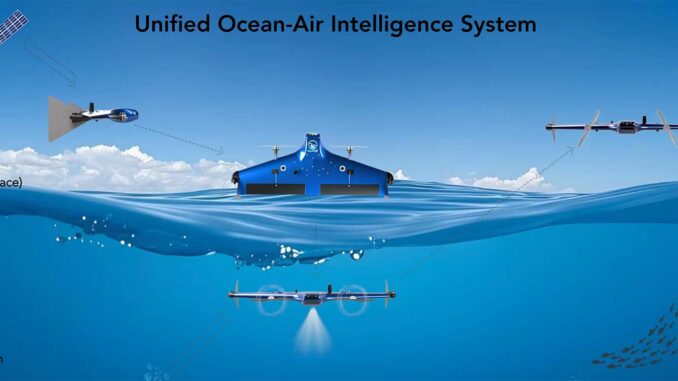

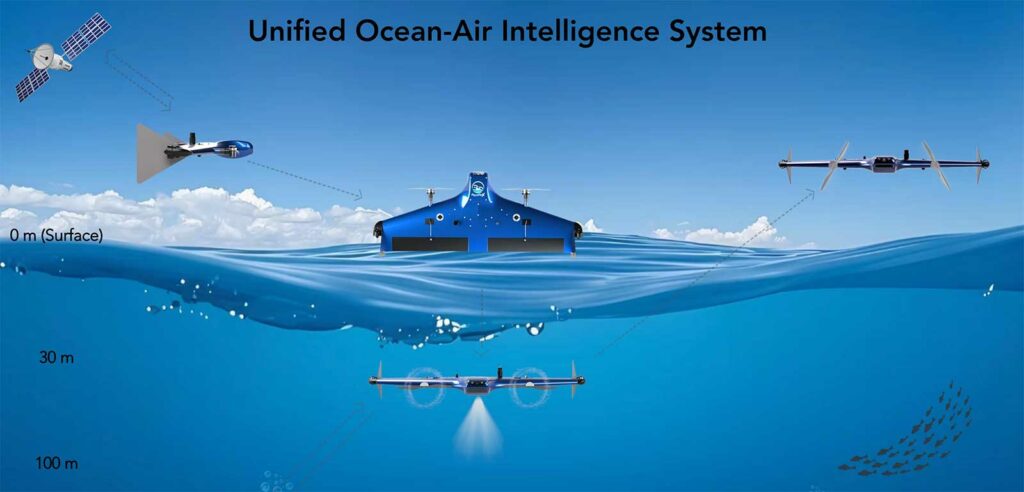

The principle of multi-domain trajectories represents the most disruptive innovation of the SiVSMD. Air-water hybrid platforms, also known as HAUVs (Hybrid Aerial Underwater Vehicles), are already operational in the form of advanced prototypes.

The recently unveiled Chinese Feiyi drone illustrates these capabilities. Equipped with a dual propulsion system—four rotors for aerial flight and four thrusters for underwater navigation—it can transition between environments with an altitude accuracy of ±0.1 meters. Its foldable arms reduce underwater drag and improve stealth. The Active Disturbance Rejection Control (ADRC) system compensates for environmental disturbances during air-water transitions.

The Naviator drone, developed by Rutgers University and marketed by SubUAS, demonstrated similar capabilities as early as 2020. This system can fly at 100 kilometers per hour in the air and reach 4 knots (approximately 7.4 kilometers per hour) underwater. Its transition from flight to diving takes only a few seconds.

These platforms exploit a fundamental tactical principle: each change of domain forces the adversary to switch to a different set of sensors. An airborne radar cannot detect a submerged object. An underwater sonar cannot track a flying drone. This discontinuity creates systemic blind spots.

Stopping as an advanced stealth technique

The use of zero or very low speed is a counterintuitive innovation. In traditional doctrine, speed protects: a fast aircraft quickly crosses defense zones, reducing its exposure time. SiVSMD reverses this logic.

A drone that lands on water or flies at very low speed—less than 10 kilometers per hour—generates a minimal thermal signature. Modern electric motors, used in amphibious drones, produce little heat in energy-saving mode. The infrared signature becomes comparable to that of floating debris or seabirds.

Coming to a complete stop also offers a decisive acoustic advantage. A drone resting on the water with its engines off becomes virtually undetectable by active sonar. Its acoustic signature blends in with the ocean’s background noise, which typically varies between 40 and 90 decibels depending on weather conditions.

Modern loitering munitions already exploit this principle. SpearUAV’s Viper system, for example, can maintain prolonged hovering to observe an urban area floor by floor before striking. Its ability to remain motionless allows it to accurately identify its target while remaining virtually silent.

This approach also creates temporal confusion for the adversary. Modern detection systems use Doppler filters to isolate moving targets from background noise. A stationary or very slow-moving object escapes these filters, becoming invisible to many radars optimized to detect fast-moving targets.

The doctrinal diagram: three generations of stealth

Kostis’ source document presents a diagram illustrating three distinct approaches to military stealth. This typology helps to understand the conceptual evolution.

Approach A represents classic environmental stealth. It relies on exploiting the terrain and natural features: terrain-following flight, sea-skimming navigation. Tomahawk cruise missiles use this technique, flying at an altitude of 15-50 meters to remain below the radar horizon. This method works, but remains geographically limited.

Approach B embodies fifth-generation stealth with the “shoot-and-scoot” tactic. A stealth aircraft fires its missiles at maximum range—up to 180 kilometers for an AGM-158 JASSM—and then quickly withdraws. This strategy minimizes exposure, but requires extremely expensive platforms and remains vulnerable to low-frequency radars.

The C approach—SiVSMD—introduces discontinuous multi-domain trajectories. A platform can combine several techniques: flying low over water, diving underwater, tactical stops, then rapid emergence for attack. This unpredictability is a form of stealth superior to simple signature reduction.

Challenges for adversarial defense systems

SiVSMD imposes radically new requirements on defenses. A traditional integrated air defense system, however sophisticated, does not simultaneously monitor the ocean depths. This segmentation creates structural vulnerabilities.

Defense must now integrate multiple types of sensors. X-band airborne radars detect high-altitude threats. L-band maritime surveillance radars monitor the surface. Passive and active sonars scan the depths. Each domain requires different technologies, specialized training, and separate command centers.

The fusion of this heterogeneous data poses a major computational challenge. A modern defense system must correlate information from dozens or even hundreds of sensors in real time. The algorithm must distinguish an amphibious drone from a dolphin, a micro-drone from a migratory bird, and an abnormal thermal signature from a natural oceanographic phenomenon.

Anti-swarm systems are emerging as a partial response. The RapidDestroyer project, developed by several European countries, aims to neutralize groups of drones using directed energy weapons—10-100 kilowatt lasers capable of destroying multiple targets per minute. But these systems remain ineffective against submerged threats.

Unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) pose a particularly complex threat. Northrop Grumman’s Manta Ray, developed for DARPA, can remain submerged for several weeks in autonomous mode. Detecting it requires fixed sonar networks installed on the seabed, which cost hundreds of millions of dollars to deploy and maintain.

Hybrid platforms: current technologies and performance

Several programs demonstrate the technical viability of the SiVSMD concept. The AVATAAR drone, developed by AquaAirX in India, can patrol 7,500 kilometers of coastline by transitioning between flight and underwater diving. Its system incorporates sonar sensors for detecting miniature submarines and combat swimmers in coastal waters.

The US multi-domain autonomous vehicle program is progressing rapidly. During exercises conducted in 2024 in the Luzon Strait, amphibious drones demonstrated their ability to maintain continuous surveillance for several days by alternating between flight, flotation, and diving. These systems transmitted intelligence data in near real time to deployed special forces.

Endurance capabilities are improving. Rotary-wing drones such as the Chinese Feiyi have 45 minutes of airborne endurance and up to 2 hours underwater at reduced speed. Fixed-wing models, such as the Dipper developed in Switzerland, can fly for several hours before diving for a 30-60 minute underwater mission.

The integration of artificial intelligence amplifies these capabilities. Visual recognition algorithms enable these drones to autonomously identify their targets. Inertial navigation systems combined with GPS maintain positioning accuracy even after repeated multi-domain transitions.

Implications for detection and counter-detection

The operational deployment of SiVSMD systems fundamentally transforms the detection-counter-detection balance. Traditional sensors are becoming partially obsolete.

Doppler radars, optimized to detect fast-moving targets, struggle to spot drones hovering or flying at low speeds. Filters automatically eliminate signals corresponding to speeds below 20-30 kilometers per hour, which are considered noise. This technical characteristic creates an exploitable window of invisibility.

Infrared sensors encounter similar difficulties. A drone with electric motors operating in economy mode generates a thermal signature of only a few watts. This emission blends in with natural variations in ocean temperature, typically 0.5 to 2 degrees Celsius between different bodies of water.

Magnetometer systems, which detect anomalies in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by metal structures, offer a partial solution. China is said to have developed an airborne quantum magnetometer, nicknamed the “death star of submarines,” capable of detecting magnetic anomalies up to 6 kilometers away. However, these systems remain sensitive to natural disturbances and are costly to deploy.

The most promising defensive response lies in distributed sensor networks. The British Royal Navy’s Atlantic Bastion program aims to create a surveillance network covering the North Atlantic. This network will integrate Type 26 frigates, surface and underwater drones, maritime patrol aircraft, and fixed underwater sensors. The estimated cost exceeds £5 billion.

Autonomy and artificial intelligence as force multipliers

Autonomy is a key factor in the effectiveness of SiVSMD. A platform capable of making tactical decisions without constant liaison with a human operator gains in resilience and unpredictability.

Modern autonomous navigation algorithms allow a drone to plan its trajectory while avoiding likely detection zones. The system analyzes underwater topography, ocean currents, commercial shipping lanes, and known enemy radar positions to calculate an optimal route. This planning is done in seconds thanks to onboard processors with 20-50 teraflops of computing power.

Artificial intelligence target recognition eliminates the need for continuous video transmission, which is a major source of detection. A drone can autonomously identify a specific military vessel by comparing its silhouette, radar emissions, and acoustic characteristics with an onboard database. Data transmission is then limited to brief coded messages of a few hundred bytes.

Autonomous swarms represent the ultimate evolution of this concept. Multiple drones coordinate their actions without centralized command, with each unit communicating with its immediate neighbors. The destruction of one or more elements does not affect the operational capability of the whole. This distributed redundancy makes these systems extremely difficult to neutralize.

Loitering munitions: immediate tactical application

Loitering munitions are the most mature application of the variable speed principle. These systems can patrol for hours at low speed before accelerating sharply towards their target.

Bluebird’s SpyX system can loiter for up to 2 hours with a communication range of 50 kilometers. In patrol mode, it flies at 40-60 kilometers per hour to conserve energy. During an attack, it accelerates to 250 kilometers per hour, leaving the target only a few seconds to react. This duality of slow and high speed optimizes both endurance and lethality.

Ukrainian TLK-150 drones, used successfully in the Black Sea, incorporate underwater capabilities. Measuring 2.5 meters long, they can carry 150 kilograms of explosives over a distance of 2,000 kilometers. Their mode of travel alternates between surface and shallow diving, making them particularly difficult to detect. In December 2025, Ukraine claimed to have struck a Russian submarine in the port of Novorossiysk with this type of system.

The cost of these munitions—typically between $10,000 and $100,000 per unit—allows for massive deployment. Faced with a defense system valued at several billion dollars, the adversary can saturate the area with hundreds of loitering munitions, forcing an inefficient allocation of defensive resources.

Fifth-generation submarines and the multi-domain

Submarines are also evolving towards the multi-domain paradigm. Saab’s A26 submarine, billed as the first fifth-generation submarine, incorporates air and underwater drone deployment capabilities.

This submarine can launch autonomous underwater vehicles (UUVs) to extend its detection range. At the same time, it can deploy aerial drones via a pressurized airlock, enabling surveillance above the surface without revealing its position. This capability transforms the submarine into a multi-domain command platform.

The air-independent Stirling propulsion system allows the A26 to remain submerged for several weeks. The acoustic signature is less than 100 decibels at 1 meter, comparable to ambient ocean background noise. This stealth, combined with deployable drones, creates a surveillance bubble of several hundred square kilometers centered on an undetectable platform.

Russian Borei-class submarines and Chinese Type 039C models also incorporate reduced signature technologies. Angular hulls, inspired by stealth aircraft, reduce sonar reflections. Composite coatings with complex internal structures absorb active acoustic waves.

The future of multi-domain warfare

The SiVSMD concept heralds a profound transformation in the way military forces will conceive offensive operations. Superiority will no longer depend solely on the technological quality of individual platforms, but on the ability to orchestrate complex operations involving dozens or hundreds of autonomous systems operating in multiple domains simultaneously.

Recent military exercises illustrate this evolution. In 2024, the US Navy tested a scenario in which amphibious drones established continuous surveillance coverage around an aircraft carrier strike group. These drones alternated between flying, positioning themselves on the surface, and diving underwater depending on tactical conditions. The system generated a continuous operational picture without exposing costly platforms to adversarial risks.

Development costs remain significant but are much lower than traditional programs. The development of an advanced amphibious drone typically requires $50-200 million over 3-5 years, compared to $10-20 billion for a stealth aircraft program. This economic asymmetry favors the rapid proliferation of these technologies.

Artificial intelligence will continue to amplify these capabilities. Mission planning algorithms are becoming capable of automatically optimizing multi-domain trajectories based on detected threats. The coordination of swarms of several hundred units is becoming feasible without continuous human intervention.

The strategic implications extend beyond the purely military sphere. An adversary with mature SiVSMD capabilities can threaten critical infrastructure—submarine cables, oil platforms, commercial ports—without exposing major conventional forces. This capability redefines the calculations of deterrence and escalation.

The technological race is intensifying. China is investing heavily in amphibious drones and multi-domain autonomous systems. The United States is accelerating its programs through DARPA and the branches of the armed forces. Europe is developing its own solutions through multinational industrial consortia. This competition will shape the strategic balance for decades to come.

The SiVSMD concept is thus much more than a tactical innovation. It embodies a doctrinal revolution in which stealth is no longer measured solely in square meters of radar cross-section, but in the ability to generate uncertainty, confusion, and unpredictability in the minds and systems of the adversary.

Sources

The Future of Stealth Military Doctrine – Theodoros G. Kostis, Joint Force Quarterly, 2025

Silent waters, smart war: how AI is reshaping anti-submarine warfare – Navy Lookout, 2025

Future Submarine Concepts and technologies: Diving into Tomorrow’s Undersea Warfare – International Defense Security & Technology

Atlantic Bastion: The Future of Anti-Submarine Warfare – Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2025

World’s first 5th-gen submarine promises stealth ops, drone delivery – Interesting Engineering, 2025

Hybrid Theory: Multi-Domain Unmanned Systems are Blurring Maritime Boundaries – Marine Technology News, 2025

Review of hybrid aerial underwater vehicle: Cross-domain mobility and transitions control – ScienceDirect, 2022

Feiyi: China’s Revolutionary Air-Water Amphibious Drone with Dual-Mode Technology – Army Recognition, 2025

Unmanned Aerial Underwater Vehicles: Research Progress and Prospects – MDPI, 2025

Design and development of autonomous amphibious unmanned aerial vehicle – Canadian Science Publishing

Submarine Stealth Vs. AI, Drones, and Sensor Networks – IEEE Spectrum, 2024

Stealth Submarines: The Next Evolution of Submarine Design – Global Defense Insight, 2024

Unmanned underwater vehicle – Wikipedia

AquaAirX AI enabled Amphibious drones and underwater drones

Loitering munition – Wikipedia

How Commercial Drones Are Redefining Loitering Munitions – Elsight, 2025

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.