Identify how to secure innovation in defense, filter the export of dual-use components, and draw inspiration from the banking sector.

Players in the defense sector are looking to maximize innovation from non-traditional suppliers, particularly start-ups and smaller companies, while maintaining strict export controls. The challenge is to prevent critical components, often of Western origin, from falling into the hands of adversaries. The challenge is made all the more complex by the fact that some components are dual-use, i.e. they can be used in both civilian and military applications. The strategies to achieve this are inspired by a sector already experienced in managing complex threats: banking. Large banks, subject to rigorous regulations, share their best practices, compliance methods and training with their smaller partners, thereby limiting risks. Similarly, large defense groups, known as primes, can provide technical and regulatory support to their smaller suppliers. The aim: to support innovation, strengthen security, increase industrial resilience and preserve the defense industry’s technological edge.

The general context

For several years now, the defense sector has been faced with a major challenge: how to maintain a technological edge while protecting its innovations from fraudulent acquisition by adversaries? This question has become more acute since the start of the conflict in Ukraine, which has been closely observed by many international analysts. According to a study conducted by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), some 450 foreign components have been identified in Russian weapons systems used in the field. Of these, 318 came from the USA, clearly illustrating the problem. The fact that 18% of these components are subject to export controls shows that, despite existing regulatory measures, adversaries are still able to obtain sensitive equipment.

The adoption of strict export controls is intended to prevent the transfer of technologies and components that could reinforce adversary military capabilities. However, it turns out that some components, produced before the introduction of these controls, were able to circulate freely. Others have probably been acquired by indirect means, via illicit supply networks. These networks are based on complex strategies: the use of shell companies, transit through poorly supervised third countries, misleading end-use declarations, etc.

The challenge is all the more acute at a time when efforts are being made to intensify cooperation between public and private players in the defense sector. Technological innovation increasingly comes from small structures, such as start-ups or mid-sized companies, which make up almost 73% of the US defense industrial base. These entities, which are agile and able to provide fresh ideas, strengthen the diversity of industrial capabilities. They are particularly effective in developing innovative technologies in fields such as sensor imaging, reconnaissance micro-UAVs (weighing just a few hundred grams) and advanced materials.

However, the growing role of small entities makes control more complex. Unlike large groups with consistent resources in terms of compliance and regulations, these small structures do not always have specialized in-house teams. The challenge is to find a model that maximizes innovation while preserving the integrity of supply chains and protecting sensitive components from inappropriate use.

The importance of private innovation in the defense sector

Technological innovation plays a central role in the defense sector. Today, the ability to develop advanced solutions quickly, cost-effectively and flexibly is a strategic advantage. The major defense groups, though solid, can no longer cover the entire value chain on their own. They are turning to start-ups or small specialized structures, capable of producing highly specialized components or introducing disruptive processes.

In the United States, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) is tasked with channelling private-sector innovation to integrate commercial products into the military arsenal. Smaller companies, often using lighter, more responsive approaches, are exploring new avenues, such as composite materials just a few millimeters thick, ultra-light integrated sensors (less than 100 g), or miniaturized inertial navigation systems on the order of 2 to 3 cm. These innovations can, for example, reduce the mass of weapon systems, increase their energy autonomy (high-density batteries of over 200 Wh/kg) or improve resilience in the face of jamming.

This dynamic is reinforced by markets worth tens of billions of euros. The US defense R&D budget reaches several tens of billions of euros a year (around 60 billion euros by 2022), while the European Union is also investing in collaborative research programs, with envelopes exceeding 2.5 billion euros for defense R&D over several years. These budgets foster the development of a dynamic ecosystem in which young companies can flourish.

However, this openness to smaller, less structured companies also presents risks. One of the main challenges concerns security of supply. As new players enter the market, the risk of technology leaks or deceptive acquisitions increases. Adversaries know how to target these entities which, lacking sufficient internal resources, are not always prepared for the rigors of compliance. It is therefore crucial to put in place a coherent approach, combining technical support, knowledge sharing and compliance assistance, so that this innovative momentum can be maintained without compromising overall security.

Export controls, a key but complex tool

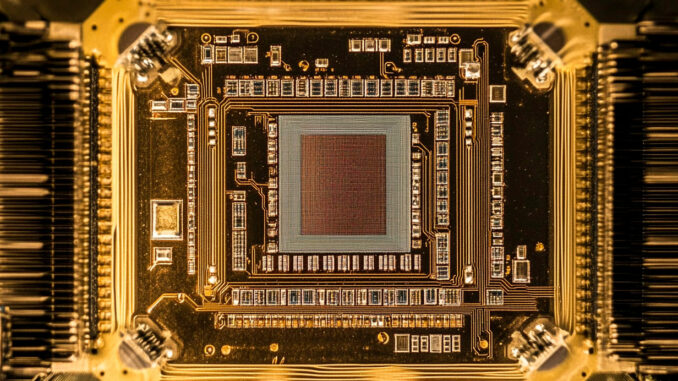

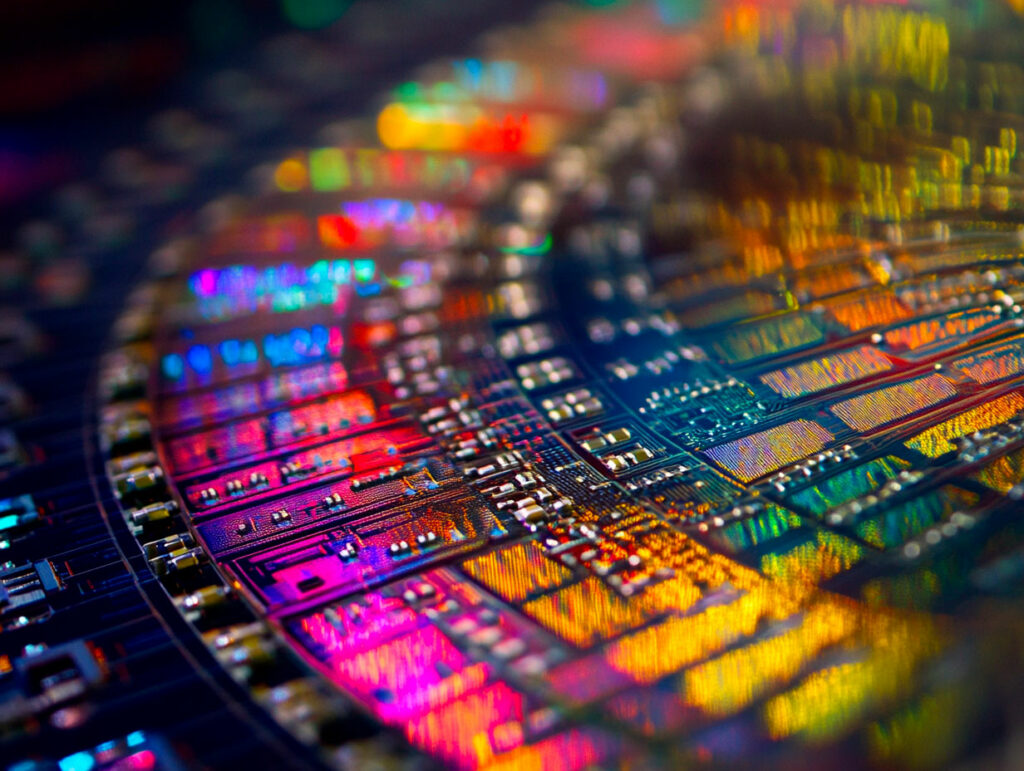

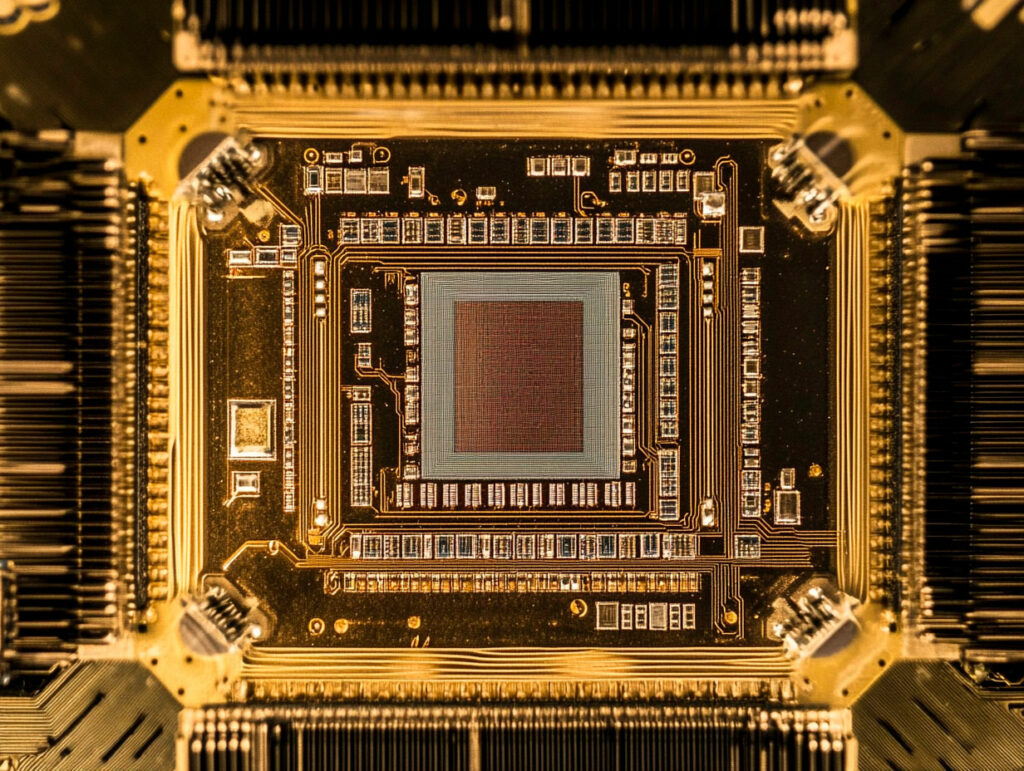

Export controls are intended to prevent the spread of sensitive technologies and components to undesirable entities or states. They apply not only to finished products, but also to more subtle elements: software, technical know-how, high-performance electronic components, specific sensors, restricted-use microprocessors and so on.

In the case of dual-use components, the situation is particularly delicate. For example, an electronic component capable of withstanding strong vibrations and extreme temperatures could be used in both an advanced imaging medical system and a military surveillance drone. It is difficult for a supplier to distinguish the actual end-use, all the more so when the buyer presents careful documentation, declares a plausible civilian use (for example, an agricultural or environmental application), or goes through intermediaries in third countries.

This phenomenon is exacerbated by illicit supply networks. These networks resort to elaborate stratagems: acquiring components via show companies located in countries with fewer controls, splitting up orders to avoid suspiciously large volumes, using multiple carriers to cover their tracks, or disguising commercial documents to conceal the identity of the end-user.

One of the major objectives of export controls is to protect the know-how of Western countries, which produce components renowned for their reliability and technical performance. In Europe, for example, specific microcontrollers produced in Germany, or infrared detection sensors manufactured in France, can find themselves diverted if the chain of conformity is not solid.

National control bodies, such as the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) in the USA, implement strict procedures and impose heavy financial penalties (ranging from a few thousand euros to several million euros) on defaulting companies. They also require these companies to strengthen their internal procedures, train their teams, and set up tools to detect red flags (false documents, payment irregularities, suspicious addresses, etc.).

Export controls, though complex, remain an essential lever for preserving technological superiority and preventing adversaries from exploiting advances in the defense sector.

Concrete examples of dual-use components

Dual-use components are a central issue in modern weapons programs. Take, for example, a spark gap trigger. This component, used in medical devices to fragment kidney stones, can also be used in a nuclear weapons firing sequence. The double-hatted nature of this component makes it particularly sensitive, as its detour for military use could have major strategic consequences.

In the field of UAVs, a simple altitude sensor measuring just a few centimetres and weighing just a few grams, originally designed for the agricultural industry to monitor crops, can also be used to stabilize a tactical surveillance micro-UAV. The same GPS guidance algorithm, designed to optimize the rapid delivery of medicines in isolated areas, can be hijacked to improve the precision of a machine carrying an offensive charge.

Semiconductors, microprocessors, graphics processing units (GPUs) and other high-performance electronic components are also targets. For example, a chip designed for a high-resolution camera (several megapixels and increased sensitivity to low light) in the field of industrial security can be inserted into an aerial reconnaissance system, enabling an enemy drone to identify targets with superior accuracy, even at night.

Public sources indicate that certain high-tech electronic components, each worth a few dozen euros, can bring considerable operational gain if properly integrated into a weapons system. The purely monetary value of a component may seem insignificant (a few euros), but its technical importance is high. A single microcontroller specialized in fast signal processing, if used in a compact radar, can improve detection range by tens of percent, thus altering the tactical balance of a theater of operations.

This complexity illustrates the need for increased vigilance. Companies need to understand that even a seemingly banal product, small in size and low in unit value, can be used for sensitive applications. It is this technical awareness and in-depth training that will make it easier to filter out suspicious requests and preserve the strategic nature of the components concerned.

Specific challenges for small businesses

Start-ups and small companies in the defense sector play a key role in the innovation ecosystem, but they often have limited resources to comply with the complexity of export regulations. Whereas a major industrial group can assign several specialists to regulatory monitoring, license verification and in-house training, a young innovative company, focused on developing a new sensor or embedded system weighing just a few hundred grams, does not always have the in-house capacity to ensure this meticulous follow-up.

What’s more, the financial constraints of these small structures can be significant. They have little budgetary leeway, which limits their ability to hire external compliance experts. Implementing a full compliance program can cost several tens of thousands of euros a year, a significant sum for a start-up entity. As a result, these companies are more vulnerable to the maneuvers of malicious actors trying to gain access to their innovations.

The challenges are also human and organizational. An engineer specializing in embedded electronics or microcontroller programming is not necessarily trained in export regulations, which can encompass thousands of part numbers, lists of controlled products, varied regional requirements (European Union, USA, Asia), or complex administrative formalities. Without prior awareness, these engineers run the risk of selling their technology, in good faith, to a dubious intermediary.

What’s more, small businesses are under intense competitive pressure. They need to bring their innovations to market quickly, and find outlets in different markets. Under this pressure, they may neglect substantive checks and rely on superficial documents. A foreign customer, presenting falsified invoices or certifications, could thus obtain a key component. This is why the defense community needs to consider solutions inspired by other sectors, to help these more fragile players adapt and integrate compliance measures from the outset.

The parallel with the banking sector

The international banking sector, faced with threats such as money laundering, terrorist financing and sanctions evasion, has developed robust internal control mechanisms. The major banks, which have dedicated compliance departments, regularly train their employees, implement analysis tools and share information between themselves. Fintechs, the banking equivalent of defense start-ups, face similar challenges: they are often driven by their products and technology, without having integrated regulatory requirements from the outset.

Just as a large financial institution trains and assists its smaller client banks to reduce risk, a large defense group (prime) could support its suppliers by offering training modules on export controls, technical guides, or customer profile assessment tools. Such an approach would bridge the knowledge gap among smaller players, thus limiting the likelihood of strategic components being acquired by unauthorized entities.

In addition, the banking sector has developed a culture of internal reporting and accountability. Every employee, from customer advisor to IT technician, is trained to spot red flags. In the same way, in a small defense company, an engineer or sales representative could be introduced to red flags: an unusual order, a request for a very specific component without technical justification, payment via an unknown company in a high-risk country, and so on.

This shared approach has the advantage of benefiting the entire chain. By drawing on the experience of the larger players, the smaller ones gain credibility and security. For example, a supplier of medical micro-UAVs designed to deliver emergency equipment (weighing around 2 kg) would have the means to check that its end customer was not intending to use these drones to deliver light offensive loads.

Transposing the model from the banking sector would result in an overall improvement in compliance levels, a reduction in the risk of technological hijacking, and better protection of the defense industrial base.

Strategies inspired by financial practices

To reinforce the integrity of the supply chain in defense, it is possible to adopt several levers inspired by the financial domain. Firstly, the implementation of mandatory training for all employees, including engineers, technicians and sales staff. Regular sessions, lasting a few hours each quarter, could be devoted to identifying red flags. Staff could be made aware of forged certificates, of buyers claiming to use the product in the civilian sector, when in fact they have suspicious links with entities under sanctions.

Secondly, the creation of internal assessment tools: compliance checklists, internal databases listing high-risk countries, or online simulators enabling engineers to test their knowledge of export regulations. Software solutions already used in banking could be adapted: for example, algorithms to detect abnormal order behavior, similar to the analysis engines that detect money laundering. Thanks to artificial intelligence, it would be possible to identify a buyer who multiplies split requests for specific components, or who frequently changes the delivery address.

Another approach would be to set up mentoring relationships between large and small companies. A mentoring program could include workshops, bi-annual meetings, best practice guides and even occasional technical support. For example, a large company producing high-end infrared sensors (renowned for their spectrally broad sensitivity, down to 14 µm, and their thermal robustness down to -40°C) could support a fledgling optical lens supplier, helping it to analyze export licenses.

Finally, defense industry trade associations and chambers of commerce could act as intermediaries. They could offer online resources, put compliance advisors in touch with start-ups, or develop trade repositories. In this way, the ecosystem would become more responsive, more aware of threats, and better equipped to prevent the misuse of components.

Practical approaches: training, awareness-raising and support

Staff training is a fundamental lever. It enables every player in the company, whether an engineer, buyer, logistics or sales manager, to identify risk indicators. For example, when an R&D engineer realizes that the end customer requires minor modifications to increase the thermal tolerance of a component, he or she may wonder why these specifications are required, especially if they correspond to the profile of a military application.

Internal awareness-raising can include practical manuals, fact sheets, short videos demonstrating common scenarios of circumvention attempts, or seminars led by outside experts. The cost of such training, a few thousand euros per session, is negligible compared to the financial and reputational risk associated with a breach of export controls. What’s more, some supervisory authorities strongly recommend such training, and may take into account a company’s good faith and efforts in the event of an incident.

Beyond training, management awareness is crucial. Managers need to understand the importance of controls, not as an unnecessary constraint, but as a sine qua non for preserving access to international markets and the confidence of institutional partners. Some governments make contracts conditional on the demonstration of a good command of export controls.

External support is also a possibility. Access to independent experts is a low-cost (a few hundred euros an hour) way of obtaining personalized advice and up-to-date regulatory monitoring. Large groups could set up a platform of shared resources, where smaller companies could find model contracts, up-to-date lists of sensitive components, or self-assessment tools.

Drawing inspiration from the financial sector, these practical approaches encourage a culture of compliance from the earliest stages of a defense company’s development. In this way, instead of integrating controls a posteriori, under the pressure of a penalty, companies will adopt them naturally, reducing overall risk and preserving the strategic nature of innovation.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.