Fighter pilots face intense stress and fatigue on long missions. How do they manage these physiological and mental limits in flight?

A fighter jet flight lasting several hours, with one or more in-flight refuelings, places extreme physiological and mental demands on the pilot. Contrary to the simplified image of brief, intense aerial combat, modern missions, particularly long-range or deterrence missions, can last between 6 and 12 hours. During this time, the fighter pilot remains alone in a cramped cockpit, unable to move, exposed to significant acceleration, temperature variations, and constant sensory stimulation.

Modern aircraft such as the Rafale, F-15EX and Su-35S are designed for extended missions, but human resilience remains a critical limitation. Operational stress, long periods of sustained concentration, tense waiting periods, lack of breaks, sleep deprivation, and the need to maintain full tactical awareness for several hours generate cumulative fatigue.

Managing this fatigue is not left to chance. It is subject to specific protocols, in-depth individual preparation, and technical coordination with ground crews. The pilot’s cognitive performance determines the effectiveness of the mission. Armed forces are now incorporating technological tools, physiological routines, and mental training to push back this limit.

Continuous physiological constraints imposed by the airframe and equipment

The airframe of a fighter jet imposes a restrictive environment in terms of temperature, ergonomics, and physiology. A fighter pilot flies in a reclined position with little room to move, wearing full flight gear (anti-G suit, life jacket, helmet, oxygen mask, etc.) weighing between 15 and 25 kg.

The mechanical stresses experienced in flight, particularly during high-g maneuvers, can reach +9G, or nine times the body weight. This disrupts blood flow to the brain and tires the muscles of the neck, back, and chest. Repeated exposure to these forces reduces alertness, causes muscle pain, and leads to microtrauma.

The thermal factor is also significant. Even in pressurized cabins, temperature variations can be extreme. At high altitudes, external temperatures drop to −50°C, and internal regulation systems do not always compensate for all variations. This adds a source of long-term thermal stress.

Finally, the oxygen mask, worn continuously, requires forced breathing under partial pressure, which causes respiratory fatigue. This constraint, combined with stress-related hyperventilation, alters oxygen saturation and affects cognitive functions.

Even though these factors are included in initial training, they require specific physical preparation. Regular muscle strengthening sessions, targeted nutritional protocols before flight, and close medical monitoring are implemented in Western air forces as well as in China and Russia.

Cognitive fatigue amplified by the tactical environment

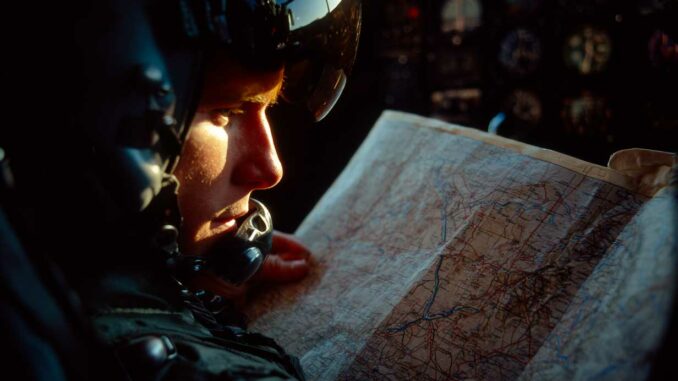

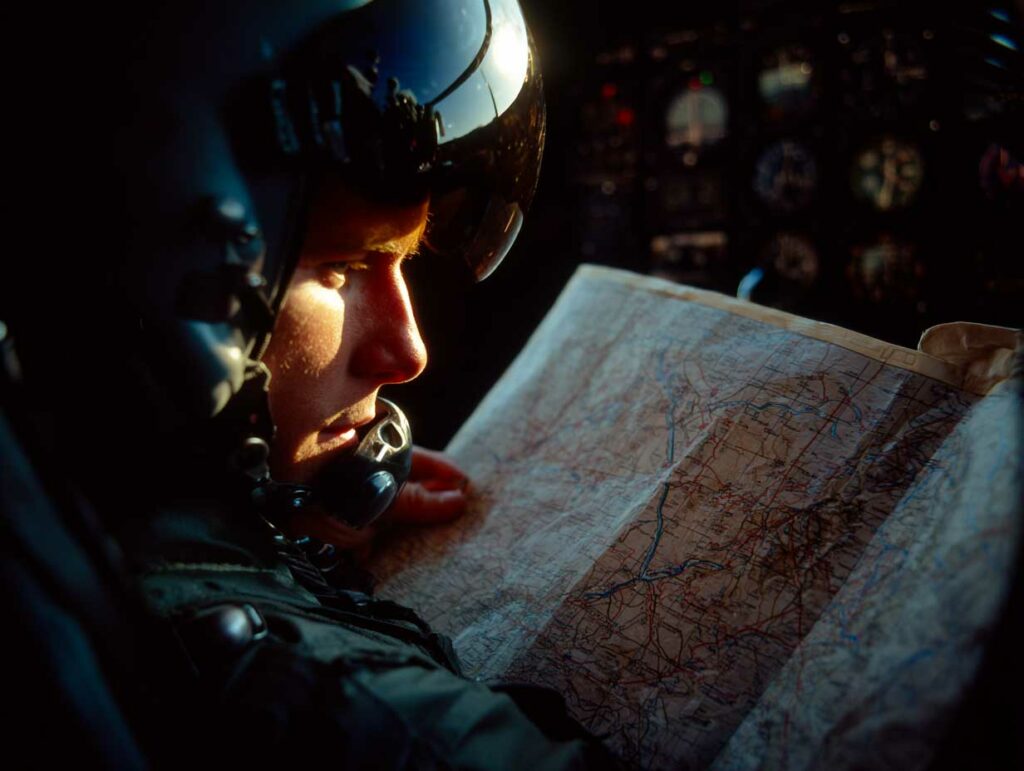

The mental load of a fighter jet flight is continuous. Unlike a civilian or automated flight, a pilot must constantly navigate, anticipate tactics, monitor sensors, communicate by radio, and interpret radar, electro-optical, and infrared data in real time. The operational environment can change rapidly, with varying intensity depending on the phase of the mission.

During long missions, often preceded by several hours of waiting on alert or on the tarmac, the circadian rhythm is often disrupted. A night flight, with mid-flight refueling, complicates the brain’s synchronization. Studies by the US Department of Defense show that cognitive alertness declines by 30% after six hours of flight time, even among experienced pilots.

In-flight refueling is a peak mental load activity. It requires extreme flight path stability and precise control of trim and speed, with error margins of less than 1.5 meters between the two aircraft. The slightest deviation can break the connection or cause an incident. This phase, often repeated two or three times per mission, requires intense concentration and causes an adrenaline rush that depletes mental resources.

To compensate, the armed forces impose strict cognitive protocols: controlled diet (avoiding fast-acting sugars before flight), timed hydration, planned micro-naps on simulators, and sometimes the use of modafinil (an authorized stimulant) in specific cases, under medical supervision. Side effects are monitored through neurophysiological tests before each mission.

Psychological support and mental preparation as the foundations of performance

Fighter pilot stress management also relies on advanced mental preparation. Since the 2000s, air forces have incorporated conditioning protocols inspired by high-level sports. Military psychologists accompany squadrons on missions, providing mental imagery, breathing control, and cognitive anchoring sessions.

The goal is to build automatic mental reflexes to reduce cognitive effort in stressful situations. For example, entering a ground-to-air threat zone causes a spike in brain activity which, if not anticipated, disrupts the sequence of actions. Through repetition on simulators, these sequences become semi-automatic, reducing the actual mental load.

Post-flight psychological debriefing is another essential component. It helps to defuse accumulated stress and assess recovery capacity before a new mission. In the case of critical missions or flights over contested areas, this follow-up becomes systematic. The US, French, and Israeli forces have all implemented post-mission rest cycles commensurate with the duration and stress of the flight.

Pilots who fly more than 200 operational hours per year are monitored with standardized cognitive assessments (attention tests, working memory, visuo-motor coordination). These assessments determine their ability to remain in high-intensity squadron operations.

Finally, some programs include virtual reality as a psychological preparation tool. The USAF is experimenting with immersive environments to simulate the physiological and emotional stress of 10-hour missions involving engagement in complex environments (urban areas, ground support, radar jamming).

An operational doctrine adapted to limit overload

The organization of long-duration flights takes these human constraints into account. A fighter aircraft flight exceeding 8 hours requires a specific doctrine. The USAF, the French Air Force, and the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force incorporate preventive planning, with squadron relays, tactical breathing windows, and flight paths that allow for predictable refueling every 2 to 3 hours.

Fuel is no longer the only limiting factor. Human capacity is becoming a determining factor. Some armies therefore prefer to send two waves of pilots to avoid prolonged fatigue. During precision strikes against targets in Syria and Libya, Rafale missions included two refuelings for durations of up to 9 hours, with alternating standby sequences during transit phases.

Collaboration between pilots within the same unit is crucial. Alternate piloting, or the redistribution of tactical functions (radar, data link, identification) within a patrol, helps spread the mental load. This cooperation is reinforced by the use of Link 16 links, which centralize tactical data and reduce the individual processing load.

Finally, human limitations require a redefinition of future architectures. Escort drone projects (Remote Carriers, Loyal Wingman) aim to delegate some critical tasks (reconnaissance, electronic warfare, support) to machines in order to preserve the pilot’s decision-making capabilities.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.