Moscow is using the Zircon hypersonic missile against Ukraine, transforming a naval weapon into a land strike tool and challenging Western defenses.

Summary

Russia used its Zircon hypersonic missile in a land strike against the Sumy region of Ukraine, after firing it from Cape Chauda in Crimea. Originally designed as an anti-ship missile to penetrate the defenses of carrier strike groups, the 3M22 Tsirkon is being adapted for ground-to-ground missions. Available data indicates a speed of up to Mach 8 to Mach 9, or more than 10,000 km/h, with a range of between 500 and 1,000 km. This real-world use allows Moscow to test a complex system in a theater where the enemy has only limited defense capabilities against this type of weapon.

The stakes go far beyond Ukraine. By demonstrating that its Russian hypersonic weapons can strike ground targets, Russia is seeking to influence the calculations of Western capitals, particularly with regard to the protection of critical infrastructure and naval forces. The message is simple: Russia can strike quickly, from far away, and with little room for the adversary to react. In reality, the actual performance of the Zircon remains shrouded in uncertainty, but its operational use, even if limited, is forcing NATO to accelerate its hypersonic defense and move beyond mere rhetoric.

The turning point: the use of the Zircon hypersonic missile against Ukraine

The use of the Zircon hypersonic missile against the Sumy region marks a qualitative change in the war in Ukraine. Until now, Moscow has mainly used more conventional ballistic or cruise missiles (Iskander, Kalibr, Kh-101) to strike energy and industrial infrastructure. The firing of Zircon from Cape Chauda in Crimea at targets described as “critical infrastructure” more than 400 km away illustrates a clear intention: to test in real-life conditions a system that has been presented for years as one of the cornerstones of Russian deterrence.

This is not the first time this missile has appeared in the conflict. Ukrainian and Western sources report that it was already fired in 2024, notably on Kiev, with at least two missiles intercepted or destroyed in flight. The frequency remains low, precisely because the Zircon is a rare and expensive weapon, with an unofficial unit cost of up to several million euros. It is far from being a disposable missile that can be fired in dozens. Each use is as much a test as it is a political message.

The strike on Sumy serves several purposes. First, militarily: the announced speed, up to Mach 9, reduces the interception window to a few tens of seconds, or even less, for Ukrainian air defense. Secondly, it serves a political purpose: the Kremlin is seeking to show that its hypersonic threats are not just empty words, especially at a time when Ukraine is obtaining more powerful Western systems. Finally, it serves a media purpose: each Zircon launch feeds into internal propaganda, which promotes the idea of Russian technological superiority over NATO.

This strike can also be seen as an admission. If Moscow had complete confidence in its conventional capabilities, it would not need to “waste” a state-of-the-art missile on a target in Ukraine. Doing so demonstrates both a desire to test the system and a need to maintain a form of psychological pressure in the absence of decisive strategic gains on the ground. In other words, Ukraine also serves as a testing ground for systems originally designed to keep the US Navy at bay.

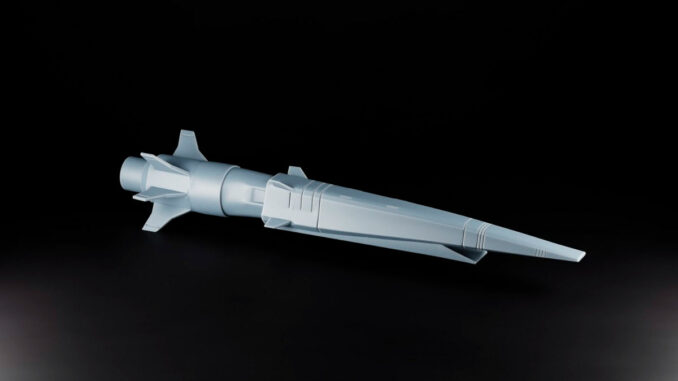

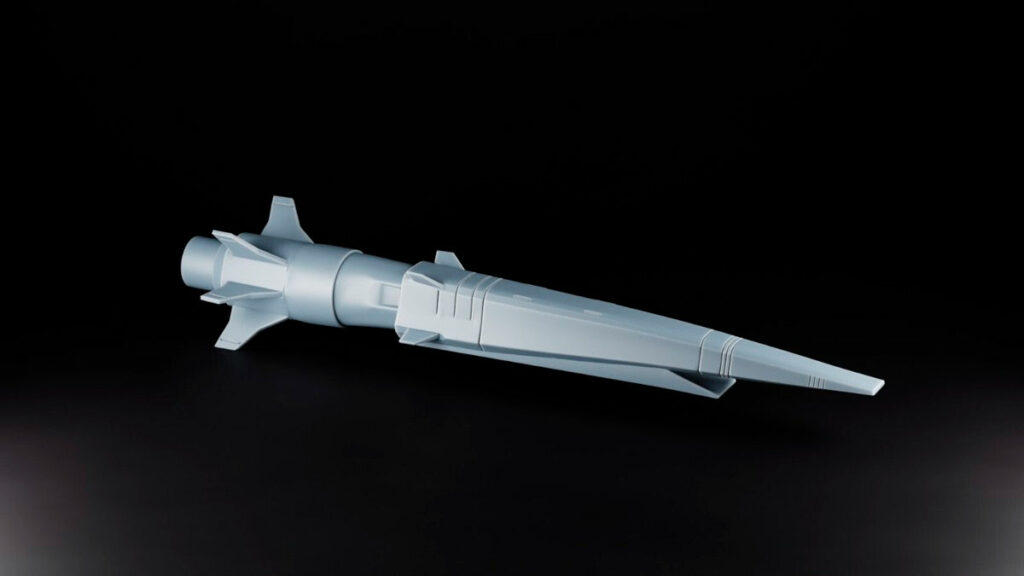

The Zircon hypersonic missile: technical characteristics and doctrine

The 3M22 Tsirkon is a hypersonic cruise missile developed by NPO Mashinostroyeniya for the Russian Navy. Technically, it is a two-stage vehicle: a solid-fuel first stage propels the missile to supersonic speed and an altitude of around 20 to 30 km, then a supersonic combustion ramjet (scramjet) takes over to accelerate it to hypersonic speeds. Public data suggests a length of around 9 m, a diameter of 0.6 m and a mass of several tons, with an estimated warhead weighing between 300 and 400 kg.

In terms of performance, most sources agree on a speed of between Mach 6 and Mach 8, with some official statements going as high as Mach 9, or between 7,400 and over 11,000 km/h at altitude. Its operational range is estimated at 500 km in low-altitude flight and up to 750 or even 1,000 km on a higher, more streamlined trajectory. In other words, a ship equipped with Zircon can theoretically strike an aircraft carrier group several hundred kilometers away, greatly reducing the reaction time of enemy defense systems.

The initial doctrine of the Zircon is clear: to serve as an anti-ship missile designed to saturate and bypass systems such as Aegis, SM-2, or SM-6. The combination of a high trajectory followed by a high-speed terminal dive, with the ability to maneuver at the end of its flight, is intended to complicate discrimination and interception. The high-altitude flight envelope, combined with significant aerodynamic heating, creates a plasma around the missile, which reduces its radar signature but also complicates its own transmissions and guidance, requiring robust electronics.

Guidance is based on inertial navigation coupled with satellite correction (GLONASS), then, in the terminal phase, on an active radar seeker. Some sources mention an infrared sensor to refine the identification of large ships, but these elements remain less well documented. This architecture is typical of modern cruise missiles, but the requirements are more stringent at these speeds: a minimal angular error at Mach 8 quickly translates into a deviation of several hundred meters if not corrected.

In technical terms, the Zircon is a navalized hypersonic cruise missile with a scramjet, optimized for large naval targets. It comes as no surprise that this base can be adapted for land strikes; the question is how accurate and reliable it will be.

The transformation of a naval weapon into a land strike tool

One of the most interesting, but also most worrying, points is how Russia is transforming a specialized naval system into a weapon for striking Sumy and other land targets. Physically speaking, a hypersonic missile does not “know” whether it is targeting a ship or a power plant; what matters is the combination of sensors, software, and flight plan. By adapting the guidance algorithms and trajectory profiles, it is possible to bring a Zircon down on a ground target with sufficient accuracy to destroy an industrial or energy site.

Tactically, the benefit for Moscow is obvious. Using a Zircon in a ground-to-ground role further complicates the planning of Ukrainian air defense. The systems delivered by the West—Patriot, SAMP/T, NASAMS—were originally designed to counter slower ballistic and cruise missiles. They can sometimes engage faster targets, but their effectiveness against a missile maneuvering at more than Mach 5 is far from guaranteed, especially if the salvo combines different vectors.

However, the capabilities of the Zircon in ground strikes should not be exaggerated. The missile was designed for large, mobile naval targets that can be detected by radar. A fixed but more compact ground target requires detailed digital mapping, terrain references, and an intelligence chain capable of providing accurate coordinates in real time. However, Russia’s record of accuracy in long-range strikes in Ukraine is mixed: many missiles have hit civilian areas with no military objective, which may reflect both intent and technical limitations.

Finally, there is a cynical dimension that no one should ignore: testing a Zircon hypersonic missile on the territory of an invaded neighbor avoids the risk of testing in a contested environment against NATO. Russia is using an already devastating conflict to validate concepts of use, gauge the enemy’s reaction, and adjust its parameters. The Ukrainians are not just adversaries; they also serve as a full-scale test bed for an arsenal that Moscow is primarily targeting against the United States and its allies.

The limitations and gray areas of Russian hypersonic weapons

Russian communications sell Russian hypersonic weapons as an unstoppable strategic asset. In reality, the picture is less clear-cut. First, the number of Zircon missiles actually available remains limited. Production only began in the early 2020s, based on tests that started around 2016. The platforms capable of launching them—Admiral Gorshkov-class frigates, Yasen-M submarines, coastal systems under development—are not deployed en masse.

Second, the first operational uses in Ukraine have not all been convincing. Ukrainian officials claim to have intercepted or thwarted several Zircon launches, particularly on Kiev. While these statements should be taken with a grain of salt, they remind us of an obvious fact: no technology is magical. Even a hypersonic missile is still subject to the laws of physics, wear and tear, manufacturing defects, programming errors, and the enemy’s ability to adapt.

On the industrial front, Western sanctions are taking their toll. The Zircon requires materials capable of withstanding very high temperatures, fast electronic components, and complex sensors. Despite talk of “import substitution,” Russia continues to circumvent sanctions by purchasing components via third countries. But quality, traceability, and volumes are not guaranteed. A series of missiles built with second-rate or even counterfeit components can very quickly result in high failure rates.

Finally, we must face facts: a missile such as the Zircon remains, for the time being, a niche weapon. It is too expensive to be fired in large quantities, too rare to be commonplace, and too politically charged to be used without careful calculation. Its real function, for the moment, lies somewhere between deterrence and demonstration. It serves as a reminder that Russia can strike command centers or naval groups with little warning, but it does not, on its own, change the overall balance of power.

The strategic consequences for NATO and anti-hypersonic defense

For NATO, the use of Zircon in Ukraine is a concrete warning. Studies on hypersonic defense have been multiplying for years; they are now moving beyond the theoretical realm. If Russia is prepared to use missiles of this type against relatively secondary land targets, there is no reason to imagine that they could not be used against an Alliance ship in the North Atlantic or the Mediterranean. Aircraft carrier groups and large air bases are becoming logical targets.

The United States has begun testing the SM-6 and Aegis systems’ ability to intercept fast-moving missiles, with some success, but the adjective most often used by US officials is “embryonic.” The Europeans are even further behind: most land-based air defense architectures are not designed for hypersonic targets, either in terms of speed, altitude, or tracking capability.

However, the battle is not lost. Hypersonic weapons have their weaknesses: sometimes predictable trajectories, thermal constraints, strong infrared signatures, and dependence on precise guidance. Solutions combining multi-frequency radars, space sensors, mid-course interception, and directed energy weapons are beginning to emerge. But they require time, money, and political will. Until now, many Western decision-makers have preferred to downplay the threat, both for intellectual comfort and budgetary reasons.

Finally, there is a dimension of nuclear deterrence that should not be underestimated. The Zircon is reputed to be capable of carrying a conventional or nuclear payload. In theory, a hypersonic strike on a NATO base or ship could be interpreted as a major attack, with a risk of escalation that would be difficult to control. Russia is therefore playing on this ambiguity: by integrating its hypersonic weapons into its conventional arsenal, it is blurring the line between conventional and strategic strikes.

The conclusion is brutal but necessary: the West has allowed Moscow to gain a practical lead in hypersonic missiles by underinvesting for years in defense and attack in this area. Today, the war in Ukraine serves as a reminder: if Western capitals do not want to suffer the same type of strikes on their soil or their forces, they will have to move from reports to concrete programs and accept that defense will be neither perfect nor cheap. For now, it is Russia that is testing its concepts on a large scale, and Ukraine that is bearing the consequences.

Sources

– The National Interest, “Russia Has Turned Its Zircon Hypersonic Missiles Against Ukraine.”

– NV / The New Voice of Ukraine, “Russia fired a Zircon hypersonic missile at the Ukrainian city of Sumy.”

– Wikipedia, “3M22 Zircon.”

– Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance, “3M22 Zircon” fact sheet.

– Army Recognition, “3M22 Zircon SS-N-33.”

– Defence Blog, “Russia tests rare anti-ship missile on Ukrainian land target.”

– Kyiv Post, “Russia’s Tsirkon Hypersonic Missiles – Reality Versus Myth.”

– Naval News, Defence Industry Europe, analyses on anti-hypersonic defense and the SM-6.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.