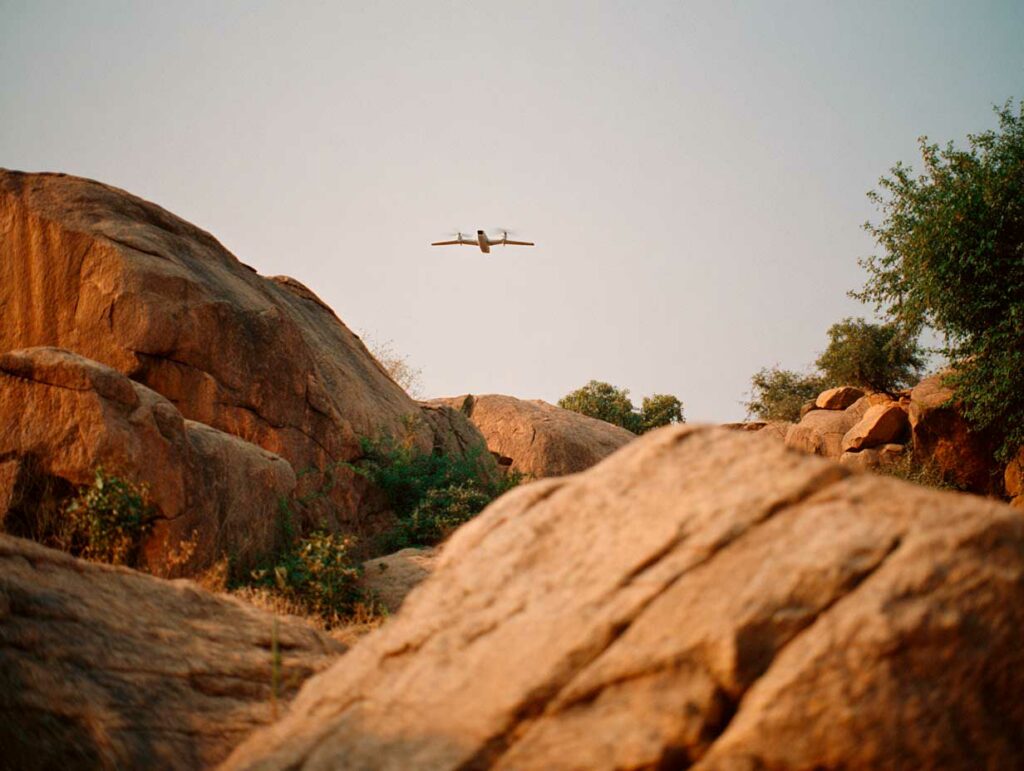

A Malian Akıncı drone was shot down near the Algerian border, reigniting regional tensions and raising questions about the use of drones.

Regional friction

Between March 31 and April 1, 2025, an Akıncı drone used by the Malian armed forces was shot down near Tin Zaouatine, an Algerian town in the Tamanrasset region, not far from the border with Mali. The incident was confirmed by Algiers, which claims to have neutralized an aircraft that violated its airspace. For its part, Bamako acknowledges the loss of a drone, while asserting that it was flying in a secure border air corridor and pointing the finger at a Russian defense system deployed by Algeria.

This episode comes amid a tense security situation marked by the gradual militarization of northern Mali, the movements of non-state armed groups, and diplomatic tensions between Mali and its neighbors. Above all, it reveals the growing role of tactical drones in African military operations, at a time when several countries are acquiring capabilities previously reserved for technologically advanced powers.

The exact circumstances of the shooting remain unclear. But the consequences are already apparent: a breakdown of trust between neighbors, questions about rules of engagement, and the risk of a technological arms race in an already fragile region. The Akıncı drone, a strategic aircraft of Turkish origin, has thus become the vehicle for an indirect confrontation between opposing visions of regional sovereignty.

A Turkish strategic drone at the heart of Malian ambitions

The Bayraktar Akıncı, developed by the Turkish company Baykar, is a new-generation drone capable of carrying out observation, strike and electronic warfare missions. With a length of 12.2 meters, a wingspan of 20 meters, and a payload capacity of 1,350 kg, it represents a step up from the conventional tactical drones used in the Sahel. It has a flight endurance of over 24 hours and an operational ceiling of over 12,000 meters.

Mali acquired its first Akıncı drones in 2024 as part of a bilateral military agreement with Turkey, reinforced by a strategic rapprochement that began with the withdrawal of French forces in 2022. Unlike the Chinese CH-4 and Wing Loong drones used by several African countries, the Akıncı offers GPS-guided strike capabilities, a satellite communication system (SATCOM) and an onboard AESA radar.

In an environment such as northern Mali—vast, poorly controlled, but saturated with armed groups—this type of drone gives the Malian army the ability to intervene rapidly beyond the front line. The model delivered to Mali is reportedly equipped with MAM-L or MAM-T guided munitions, produced by Roketsan, with a range of 15 kilometers.

However, this capability gain raises regional coordination issues. The flight of an Akıncı in the immediate vicinity of a sensitive border, without prior notification to the Algerian authorities, creates a gray area. This is particularly true given that the drone flies at high altitude and can operate outside the conventional radar range of African armies, except for forces equipped with advanced surveillance systems, as is the case in Algeria.

Algerian defense equipped with modern Russian technology

Algeria has significantly strengthened its air defense capabilities in recent years. The country has several advanced Russian systems, including Pantsir-S1, Tor-M2, and, most notably, S-300PMU2 batteries, capable of intercepting air targets at ranges of over 150 kilometers. In the south, the Algerian army has reportedly deployed a mixed air surveillance and electromagnetic detection network, adapted to desert areas with little coverage by conventional civilian control.

According to Algiers, the Malian drone penetrated several kilometers into Algerian territory, in an area close to a protected military site, which would have justified immediate interception. No details have been provided on the system used, but the characteristics of the shot suggest the use of a medium-range surface-to-air missile guided by semi-active radar.

Mali, for its part, claims that the drone did not cross the border but may have been targeted from Algerian territory while flying over an undefined area near the Lerneb post in the Kidal region. Bamako believes that the interception was carried out with technical support from Russian instructors, which Algeria has not confirmed but which remains plausible given the military cooperation between Moscow and Algiers.

The incident reveals an unresolved area of friction at the diplomatic level. The central Sahara, due to its size and the vagueness of some administrative boundaries, remains prone to incidents of misinterpretation. But in this case, the use of sophisticated technology in a sensitive environment has turned a simple surveillance flight into a diplomatic incident.

Military regionalization marked by the proliferation of drones

This incident is part of a broader trend toward the militarization of African borders, where drones have become tools for surveillance, coercion, and sometimes tactical projection. Niger, Chad, Algeria, Morocco, but also Burkina Faso and Mali have acquired more than 200 military drones in five years, mainly supplied by China, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

The spread of these systems, often without clear regional oversight, is creating a climate of mistrust between neighbors. Border incidents involving drones have increased: unauthorized flights over Libyan territory, attempts to fly over a military center in Mauritania, and the neutralization of a drone on the Algerian-Moroccan border. The case of Mali and Algeria is therefore not isolated, but reveals an uncoordinated surveillance race with potentially serious consequences.

Added to this is the proliferation of asymmetrical partnerships: Turkey sells its drones with training, Russia supplies integrated radars with instructors, and China delivers its aircraft without any interoperability requirements. This fragmentation of operational doctrines complicates the establishment of de-escalation mechanisms. Each drone becomes an instrument of territorial assertion, used without coordination or information sharing.

In the specific case of Tin Zaouatine, no alert mechanism was activated. Neither the African Union Mission, the ECOWAS, nor the UN were informed of a sensitive flight in a high-risk area. The lack of a common framework exacerbates tensions and pushes each state to act in isolation, even if it means further destabilizing the regional balance.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.