Su-75 Checkmate stealth fighter, derivative drone, and export: Moscow promises a first flight in 2026 despite the war, sanctions, and a highly competitive market.

Summary

The Su-75 Checkmate is presented by Moscow as an “affordable” Russian stealth fighter, intended primarily for export. Officially, Russia is now promising a first flight in early 2026, even though no actual prototype has yet been shown publicly. The single-engine aircraft is designed to carry up to 7.4 tons of weapons for a maximum takeoff weight of 26 tons, with an announced speed close to Mach 2 and a range of approximately 2,800 to 3,000 km.

Russian manufacturers are already talking about a complete family of aircraft based on this project: a two-seater version, an unmanned derivative, and industrial cooperation with Belarus to reduce costs and reassure potential export customers. But these ambitions are hampered by a simple reality: heavy Western sanctions, difficulties in mass production even for the Su-57 program, the collapse of Russian fighter exports, and aggressive competition from China and Western 5th/6th generation programs.

The Su-75 is therefore less a finished product than a tool for communication and commercial prospecting. Until a prototype actually flies, the project will remain a risky industrial gamble in a fighter aircraft market valued at more than $50 billion per year and expected to grow moderately between now and 2035.

The Su-75 Checkmate project and its positioning

A single-engine fighter designed for export

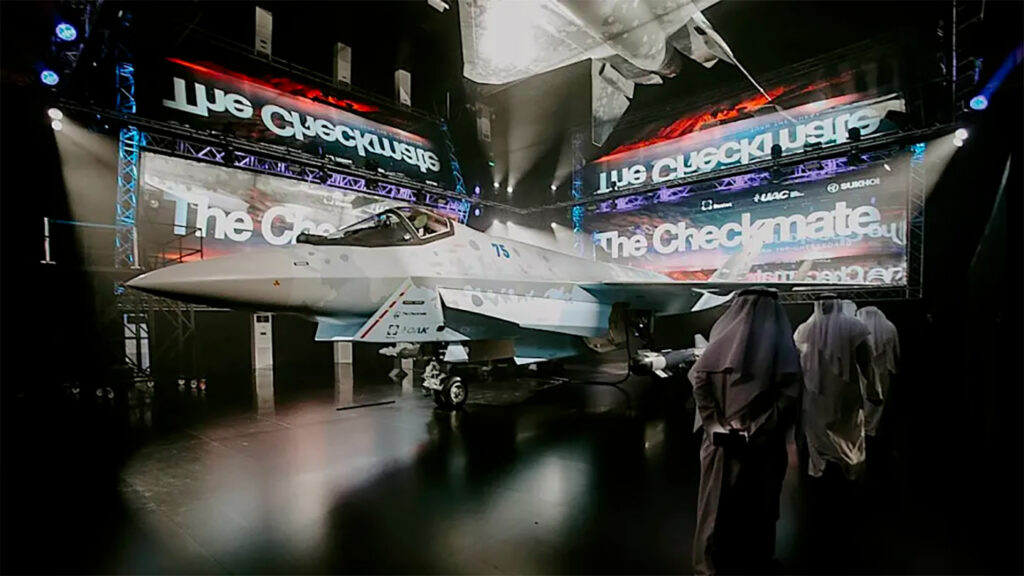

Officially unveiled at the 2021 Dubai Airshow, the Su-75 Checkmate is defined by United Aircraft Corporation as a “Light Tactical Aircraft.” In reality, the figures place it more in the medium fighter category. It is around 17.5 m long, with a wingspan of nearly 11.8 m and a maximum takeoff weight of 26,000 kg. These dimensions place it between an F-35A (approximately 15.7 m and 31.8 t maximum weight) and a Su-57 (20 m and nearly 34 t), confirming its intermediate positioning: more compact and less expensive than a heavy twin-engine aircraft, but much more ambitious than a simple light fighter.

On paper, the Checkmate can carry up to 7,400 kg of payload, equivalent to a mix of air-to-air missiles, guided bombs, and additional fuel tanks. In practice, this load will be distributed between an internal bay and external hardpoints. The announced performance figures suggest a maximum speed of between Mach 1.8 and Mach 2, or around 2,200 km/h at high altitude, with a range of approximately 1,500 km without refueling, taking into account a realistic mission profile.

This profile corresponds exactly to the need for a single-engine fighter for countries with limited budgets: high versatility, theoretically low purchase cost, and simplified maintenance compared to a heavy twin-engine aircraft. The problem is that this niche is already occupied by the F-16V, the possible export version of the Indian Tejas Mk1A, the modernized Chinese J-10, and, in a higher category, the widely used F-35A. The Su-75 is therefore arriving late, with no visible prototype, facing aircraft that are already in service or at a very advanced stage of development.

Mainly frontal stealth and a classic architecture

In terms of stealth technology, the Su-75 adopts solutions already seen on other Russian aircraft: DSI (diverterless supersonic inlet) ventral air intake, angular shapes, and panel alignment to limit radar reflections. Recent renderings show an evolution in the design: enlarged trailing edge, longer flaperons, wing root extended forward, redesigned nose and canopy with serrated edges. All of this is aimed at reducing the radar signature in the forward axis, where enemy radars are most likely to detect the aircraft.

However, we must remain realistic: like the Su-57, the Su-75 does not seem to be seeking “all-around” stealth comparable to the F-35. Photos and models still show compromises: a conventional nozzle, numerous external hardpoints planned, and main landing gear and compartments that do not reach the level of integration seen in the most advanced Western programs. The aircraft aims to strike a balance between sufficient discretion, controlled costs, and high carrying capacity, rather than extreme stealth.

The announced development and the reality of Russian industry

An officially tight schedule, unofficially uncertain

In Dubai in 2025, Sergey Chemezov (Rostec) and Sukhoi’s chief test pilot, Sergey Bogdan, stated that the first prototype is being finalized on the assembly line and that flight tests could begin in “early 2026.” In other words, Russia is promising a first flight about five years after the model was unveiled, which in itself would be nothing unusual… if we had seen even a single photo or leak showing a complete aircraft.

However, to date, there is no credible visual evidence beyond mock-ups, 3D renderings, and models displayed at trade shows. This is in stark contrast to the Su-57 program, or the S-70 Okhotnik-B drone: from the early years, actual prototypes were visible, photographed at airfields or in flight. Here, there is nothing of the sort. This naturally fuels doubt: is the Su-75 project really progressing, or is it mainly serving as a commercial showcase to maintain the illusion of a future range of modern, low-cost Russian fighters?

Chemezov points out that it takes “10 to 15 years to design an aircraft,” which is factually correct. But implicitly, this also means that even if the first flight takes place in 2026, true maturity, with an operational standard, would not be achieved before the 2030s, at best. In the meantime, more than 1,500 F-35s will have been delivered, China will have rolled out its J-31/J-35, and Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy will be making progress on their GCAP or equivalent programs.

The concrete impact of sanctions and the war in Ukraine

Russian communications minimize the effect of Western sanctions. However, the figures are clear: Rostec acknowledges that its defense exports have halved since 2022, in favor of urgent domestic orders for the Russian army. The priority is simple: to produce ammunition, simple drones, tanks, and surface-to-air systems, rather than experimental fighters for export.

In addition, the Su-57 production lines have already suffered from dependence on foreign components, particularly in the field of radar and electronics. OSINT analyses indicate that production lines are weakened by restrictions on Western components, forcing manufacturers to find less efficient substitutes or resort to parallel channels. When a country is already struggling to deliver 18 Su-57s in two years out of an order for 76 aircraft, promising a completely new Russian stealth fighter for export is more a matter of political rhetoric than rigorous industrial planning.

Finally, the war in Ukraine is absorbing a considerable amount of human, financial, and industrial resources. Every ruble invested in a program like the Su-75 is a ruble that does not go to kamikaze drones, artillery, or surface-to-air systems that are immediately useful on the front lines. In this context, it is difficult to believe that the Su-75 will actually be a priority, even if it remains useful as a loss leader at trade shows.

The fighter jet market and international competition

A moderately growing but already saturated market

The fighter jet market is estimated to be worth around $52.9 billion in 2025, with a projection of $79 billion by 2035, representing annual growth of around 4%. Translated into euros, this represents between €49 billion and more than €73 billion, depending on exchange rates. This is not insignificant, but it is not an unlimited El Dorado either: budgets are tight, and major structural programs (F-35, Rafale, Typhoon, J-10C, J-35, KF-21, etc.) already occupy a large part of the space.

In the export customer segment targeted by the Su-75 – the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and Latin America – Russia faces several challenges:

- Competition from the F-35, which is becoming the de facto standard wherever Washington allows it.

- The rise of China, which offers aggressive financial solutions and a political package that is less exposed to US sanctions for certain countries.

- Local programs, such as the Tejas in India or the Sino-Pakistani JF-17, which respond to sovereignty considerations.

Added to this is the CAATSA framework: any country importing an advanced Russian system is exposed to secondary US sanctions, which is putting many capitals off.

In this context, Moscow has announced contacts with the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Algeria, Vietnam, and even India. But no firm orders have been placed to date. For a rational decision-maker, investing several billion euros in a fifth-generation fighter jet that has not yet flown, whose industrial chain is experiencing difficulties with other programs, and which carries the risk of economic sanctions, remains a very risky gamble.

A commercial offensive with Belarus as a relay

The recent communication around a joint Russian-Belarusian production of the Su-75 is clearly part of an attempt to reassure: cost sharing, expanded industrial base, possibility of future local assembly for certain partners. In reality, Belarus brings neither decisive technology nor a significant domestic market. The message is primarily political: to show that the project is alive, that partners exist, and that the program is not solely Russian.

For some countries under sanctions or at odds with the West, such as Iran, a Russian single-engine fighter jet that is supposedly stealthy may seem attractive, if only as a bargaining chip with other suppliers. But here again, the first serious question will be: is there a real aircraft, a credible schedule, and logistical support capacity over 30 years? Until Rostec provides concrete answers, the argument of a “competitive” price will remain theoretical.

The unmanned version and the aircraft family logic

An ambitious drone derivative on paper

At the 2025 Dubai Airshow, a reworked model of an unmanned derivative of the Su-75 is presented. It clearly shows a set of electro-optical sensors under the fuselage, with an EOTS under a transparent fairing, additional IR/EO sensors towards the front, and an opening on top of the nose, a typical configuration for a distributed aperture system (DAS) for panoramic vision.

The idea makes sense: if the piloted aircraft sees the light of day, it will serve as the basis for a combat drone of comparable size, designed to operate in cooperation with manned fighters or to act semi-autonomously. Heavy combat drones are becoming a key segment: the United States, China, Europe, Turkey, and India are all investing in them. Offering a derivative of the Checkmate would allow Moscow to claim entry into this club.

But here again, we are still in the realm of concept. Creating a reliable stealth combat drone requires software integration, sensors, data links, and autonomy algorithms that the Russian industry has not yet demonstrated on a large scale. The S-70 Okhotnik-B is promising, but still a long way from a robust operational fleet. Under these conditions, announcing an unmanned derivative of the Su-75 amounts to piling promises on a foundation that does not yet exist.

A communication strategy rather than a solid industrial plan

Talking about a complete “family” – single-seater, two-seater, unmanned – even before the first flight of the basic model is revealing: it is about selling a story rather than a product. It is a way of occupying the field in the face of China, which is already showcasing the J-35 and several stealth drones, and in the face of Western programs that are shifting towards collaborative human-machine architectures.

From a strictly technical point of view, it would be more credible to concentrate resources on a single prototype, developed to pre-production standard, and then to develop a drone version. But Russia needs visible signals for its political partners and domestic opinion: the Su-75 ticks all the boxes – stealth, single-engine, export, drone derivative – with a real cost that is still limited as long as nothing is flying.

The real prospects for the Su-75 Checkmate

If we forget the official rhetoric for a moment, the diagnosis is quite clear. Technically speaking, the concept of a single-engine Russian stealth fighter, halfway between the Su-57 and older fighters, makes sense. The multi-role single-engine segment remains the most promising in the world, as shown by the predicted dominance of single-engine aircraft in the combat aircraft market forecasts for 2035.

But from an industrial and geopolitical standpoint, everything is working against Russia’s ambitions:

- Production lines that are already weakened.

- Long-term Western sanctions.

- Budgetary priority given to the war in Ukraine.

- Competition from China, which is targeting the same customers.

- Risk of sanctions for any buyer who bets on the Checkmate.

It is necessary to be blunt here: until Moscow has at least one prototype in flight, the Su-75 will remain closer to a marketing model than a credible Russian fighter jet. Foreign military decision-makers are well aware of this. The next step, the only one that will really matter, will be the release of tangible evidence of flight tests: complete aircraft, systematic test flights, firing campaigns. Without this, the glossy trade show brochures will only convince those who already believe in them.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.