The world’s democracies need to protect vital undersea infrastructure from sabotage, a major strategic threat.

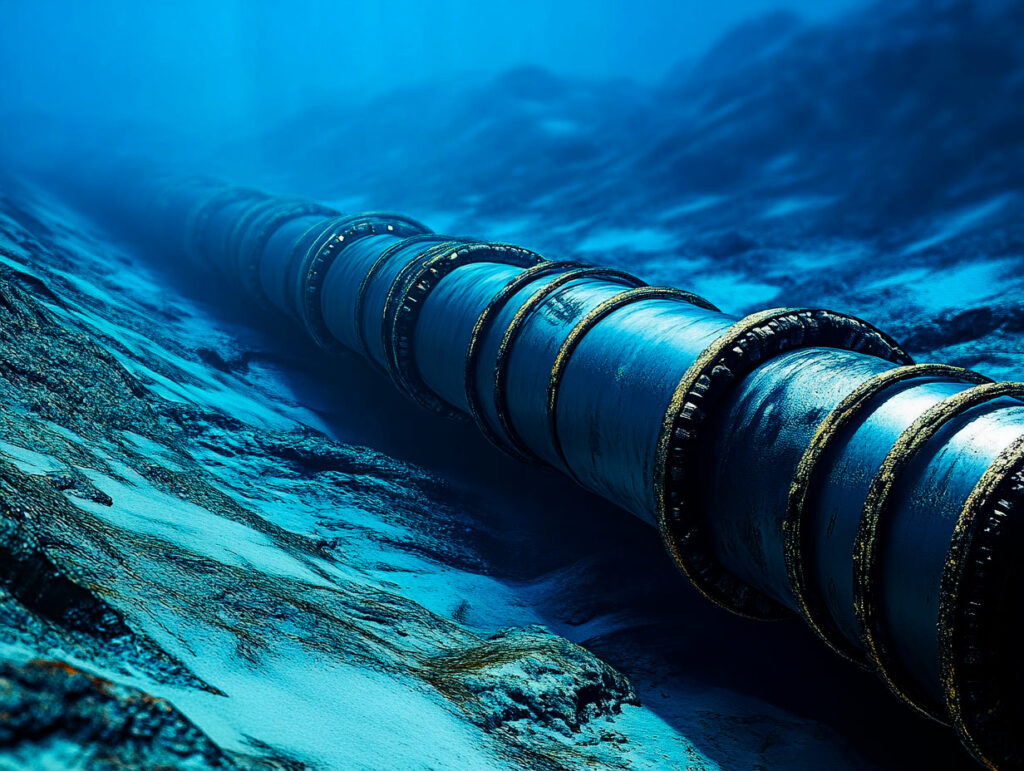

Submarine infrastructures, such as data cables and energy pipelines, carry around 98% of the world’s Internet traffic and more than $10,000 billion in daily financial transactions. However, these vital networks are increasingly vulnerable to acts of sabotage, jeopardizing global energy, economic and digital security. Several recent incidents in Europe and Asia reveal growing threats from vessels operating under opaque jurisdictions. This article analyzes the strategic stakes, the players involved and the solutions envisaged.

The growing threat of submarine sabotage

Recent incidents in the Baltic Sea and Asia show that underwater infrastructures have become strategic targets. In November 2023, a Chinese vessel was accused of severing two fiber optic cables linking Germany, Finland, Sweden and Lithuania. A month later, a Russian oil tanker was reported to have cut an undersea power cable between Finland and Estonia, also damaging four telecom lines.

These acts, described as probable sabotage, highlight a new form of hybrid warfare. Submarine pipelines and cables are vulnerable, as they are often located in little-surveyed areas, at depths that are difficult to access. As an example, the Nord Stream pipeline explosions in 2022 highlighted the destructive impact of such attacks: repairs were estimated at several billion euros.

Submarine infrastructures represent a strategic global network. Cables carry around 98% of the world’s Internet traffic, and handle $10,000 billion in financial transactions every day. Pipelines connect the main centers of energy production and consumption. Their sabotage can lead to major disruptions in global energy and financial markets.

The suspicious role of phantom fleets

Sabotage also appears to be linked to “ghost fleets”, made up of aging vessels, often poorly maintained and operating without adequate insurance. These ships are used to circumvent international sanctions, particularly against Russian oil. For example, the oil tanker Eagle S, involved in the December 2023 incident, reportedly dragged its anchor for almost 100 km in the Gulf of Finland, damaging critical infrastructure.

These fleets are difficult to monitor, as they often deactivate their transponders to avoid satellite tracking. This complicates the identification and prevention of malicious acts. Their use in sabotage operations suggests an escalation of geopolitical tactics.

However, investigations are limited by international law. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, ships enjoy the right of “innocent passage”. This legal protection hampers intervention, even in cases of suspicious behavior.

Military and strategic response

Faced with this growing threat, Western nations are beginning to take action. NATO has launched the Baltic Sentry mission, mobilizing frigates, naval drones and maritime patrol aircraft to monitor the Baltic Sea. The aim is to protect critical infrastructure from sabotage and identify suspicious behavior.

Satellites also play a crucial role in this strategy. They can track ship movements in real time and detect transponder disconnections. However, such surveillance requires considerable investment. For example, modernizing maritime tracking capabilities could cost several billion euros over ten years.

Naval forces must also adapt their practices to meet new tactics. Seizures of suspicious vessels, such as that of the Eagle S by the Finnish authorities, show an increased willingness to take firm action. However, such interventions remain risky, as they could trigger diplomatic or military reprisals.

The role of the private sector in infrastructure protection

Private operators, who own and operate the majority of submarine cables and pipelines, play a key role in protecting them. At present, infrastructures lack redundancy, making them vulnerable to disruption. A damaged cable can disrupt thousands of Internet connections and slow down international financial transactions.

Investment in back-up cables and repair vessels is essential. According to experts, building new redundancy capacity would cost around 2 to 3 billion euros over the next five years. For example, laying additional cables linking Europe and Asia could reduce repair times by 30%.

In addition, advanced surveillance technologies, such as underwater acoustic sensors, could detect suspicious activity in the vicinity of critical infrastructures. These measures, while expensive, are less costly than the disruption caused by concerted attacks.

Economic and geopolitical implications

Acts of underwater sabotage have major consequences for global economic and geopolitical stability. For example, an attack targeting pipelines in winter could trigger an energy crisis in Europe, leading to higher gas prices and shortages for consumers. In 2022, the explosion of the Nord Stream pipelines contributed to a 35% increase in gas prices in Europe.

On the geopolitical front, these incidents aggravate tensions between the major powers. China and Russia are often accused of these acts, although direct evidence is scarce. This situation is fuelling a climate of mistrust and prompting Western nations to strengthen their strategic alliances.

Finally, disruptions to data cables can have a global economic impact. A major interruption to financial networks could lead to losses of several billion euros a day for banks and businesses.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.