Extensive technical analysis of the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988): causes, actors, key battles, outcomes, and long-term consequences.

The Iran-Iraq War, fought from September 1980 to August 1988, was one of the longest conventional conflicts of the 20th century. It began with Iraq’s invasion of Iran, driven by border disputes and political tensions. The war saw extensive use of trench warfare, chemical weapons, ballistic missiles, and attacks on civilian infrastructure. Both nations mobilized large populations and spent billions on military campaigns. Despite the vast destruction, no territorial gains were secured by either side. The conflict ended with United Nations Security Council Resolution 598, without a clear victor. The war resulted in an estimated 500,000 to 1 million casualties, billions in economic damage, and a prolonged geopolitical impact across the Middle East. It reshaped regional alliances, intensified internal repression in both countries, and disrupted oil markets for nearly a decade.

What were the reasons for the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

The primary cause of the Iran-Iraq War was a combination of territorial disputes, political ambitions, and ideological conflict. The most direct reason was the dispute over the Shatt al-Arab waterway, a strategic river that forms the boundary between Iran and Iraq. Iraq had long claimed full sovereignty over the waterway, while the 1975 Algiers Agreement had forced Baghdad to share control with Iran, a concession Saddam Hussein sought to reverse.

Another factor was Iraq’s fear of Shia political influence following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which overthrew the Shah and established a theocratic regime under Ayatollah Khomeini. Saddam Hussein saw the revolution as a threat to his secular Ba’athist government, especially given Iran’s calls to export its Islamic ideology, which could destabilize Iraq’s majority-Shia population.

Economically, Iraq was recovering from years of military spending and saw Iran’s oil-rich province of Khuzestan as a strategic acquisition. Baghdad believed Iran’s military was weakened by post-revolution purges, making it vulnerable.

Geopolitically, Saddam aimed to establish regional dominance and present Iraq as a counterweight to revolutionary Iran. He also wanted to position Iraq as the leader of the Arab world, gaining support from countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Jordan who feared Iranian expansionism.

The broader Cold War dynamics also played a role. Western nations and the Soviet Union saw Iraq as a barrier to Iranian influence and were willing to provide support to contain Tehran. Iraq miscalculated that a short, decisive strike would destabilize the new Iranian regime. Instead, it initiated a prolonged war with no clear exit strategy.

The convergence of border grievances, sectarian fear, economic motives, and regional competition made the conflict inevitable. The war was not just a response to local disputes but also to strategic aspirations and fears of ideological contagion across the Middle East.

Who was involved in the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

The primary belligerents were the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Republic of Iraq. Both nations mobilized vast military and civilian resources over eight years of war.

Iraq, under the Ba’athist regime of Saddam Hussein, initiated the conflict with a ground and air invasion in September 1980. Iraq’s military was better organized at the outset, with support from multiple external actors. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan, Egypt, and other Arab nations provided Iraq with financial aid, intelligence, and logistical support. Iraq also received advanced weaponry from the Soviet Union, France, China, and Brazil. The United States and Western European countries covertly supported Iraq through dual-use technologies, satellite data, and financial mechanisms.

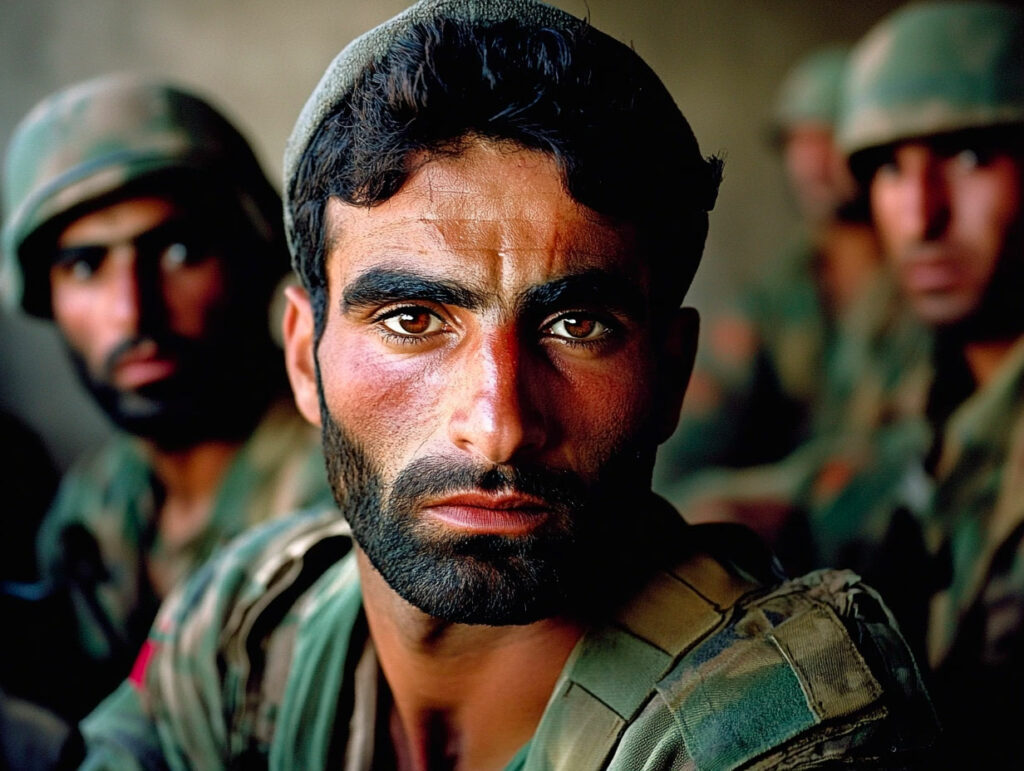

Iran, despite international isolation after the 1979 revolution, mobilized large numbers of volunteer fighters through the Basij militia, alongside the regular army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Iran relied on stockpiled U.S.-made equipment from the Shah’s era and supplemented it through black-market purchases, limited North Korean and Chinese exports, and domestic manufacturing.

Iran received minimal official external support. Syria and Libya were rare allies. The Iran-Contra affair later revealed that the United States indirectly provided arms to Iran through Israel, intending to secure the release of hostages in Lebanon while simultaneously supporting Iraq.

Beyond state actors, non-state groups such as Kurdish factions in Iraq and Baluchi groups in Iran occasionally contributed to internal destabilization efforts, often encouraged by the opposing side.

The conflict drew indirect global involvement. The Soviet Union and the United States, although adversaries, both saw an interest in containing Iranian influence. The UN, Red Cross, and non-governmental humanitarian agencies were involved in documenting war crimes and delivering aid to civilians and prisoners of war.

The war became a proxy battleground, shaped by global strategic interests but fought with high human cost at the regional level. Despite extensive external support, neither side achieved dominance.

The leaders of the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

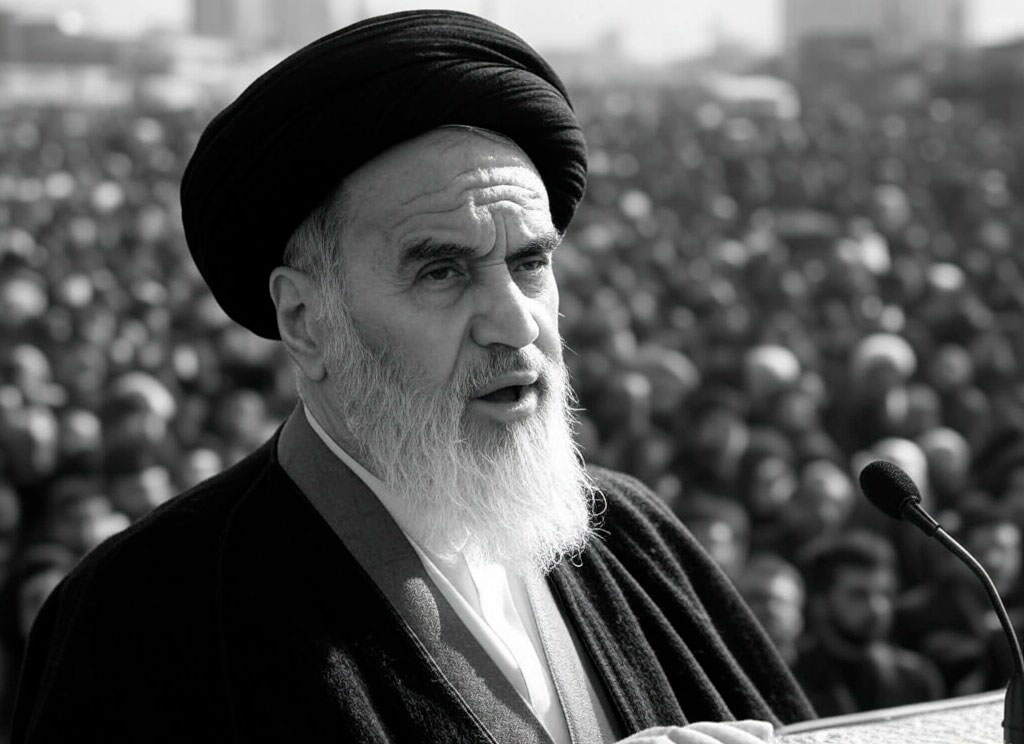

The conflict was largely driven by the decisions and actions of two dominant leaders: Saddam Hussein of Iraq and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran.

Saddam Hussein, President of Iraq since 1979, led a centralized state apparatus based on Ba’athist ideology. He consolidated power through purges of political opponents and positioned himself as a defender of Arab nationalism. Saddam initiated the war, believing that Iran was militarily weakened after the 1979 revolution. His decision to invade in September 1980 was based on both strategic calculations and a desire to strengthen domestic authority. Saddam exercised direct command over military planning and frequently intervened in battlefield decisions, often bypassing military command structures. His government was responsible for extensive use of chemical weapons, attacks on civilian populations, and the Anfal campaign against Kurdish regions.

Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s Supreme Leader, was the symbolic and political head of Iran’s post-revolution theocracy. Although President Abolhassan Banisadr and later Ali Khamenei held formal office during parts of the war, real authority rested with Khomeini. He mobilized Iranian society through ideological rhetoric, presenting the war as a sacred defense of the Islamic revolution. He sanctioned the use of mass human-wave attacks, particularly by the Basij militia, resulting in heavy Iranian casualties.

Military leadership on both sides shifted repeatedly. Iraq’s Generals—including Adnan Khairallah and General Maher Abd al-Rashid—played key roles in operational planning. Iran relied heavily on the IRGC commanders, such as Mohsen Rezaee and Ali Shamkhani, who lacked formal military training but held significant influence.

Both leaders ignored ceasefire proposals for years, prioritizing ideological and political survival over resolution. Khomeini only accepted the 1988 ceasefire reluctantly, comparing it to drinking poison, while Saddam declared victory despite failing to meet any strategic objective.

The leadership on both sides prolonged the war by refusing compromise and relying on large-scale mobilization rather than tactical efficiency. Their personal authority and rigid political ideologies directly shaped the scale, methods, and duration of the conflict.

Was there a decisive moment?

The Iran-Iraq War lacked a single defining moment that dramatically altered its outcome. However, several military and geopolitical developments between 1986 and 1987 contributed to a gradual shift in momentum.

One such event was Operation Karbala-5, launched by Iran in January 1987, aiming to capture Basra, Iraq’s second-largest city. This operation involved over 150,000 Iranian troops and marked one of the most violent phases of the conflict. Despite heavy losses, Iranian forces came within 15 kilometers of Basra. Yet, stiff Iraqi resistance and intensive use of artillery and chemical weapons halted the offensive. The failure to capture Basra was a psychological and strategic blow to Iran. It demonstrated the limits of Iran’s manpower-intensive warfare and eroded public morale.

Simultaneously, Iraq began a massive rearmament program, acquiring advanced missile systems, new aircraft, and better artillery. The country also escalated its use of chemical weapons, particularly during Operation Tawakalna Ala Allah, a counteroffensive campaign that pushed Iranian troops out of several territories by late 1987.

Another significant factor was the “Tanker War” escalation in the Persian Gulf. Iraq started targeting Iranian oil shipments, aiming to cripple Iran’s economy. In response, Iran attacked neutral shipping and Gulf oil infrastructure. The United States, concerned about energy supply routes, intervened militarily through Operation Earnest Will, escorting Kuwaiti tankers and engaging directly with Iranian naval assets. This included the USS Stark incident in 1987, when an Iraqi missile killed 37 American sailors, and Operation Praying Mantis in 1988, during which U.S. forces destroyed much of Iran’s naval capability.

By mid-1988, Iraq had regained most lost territories and had secured superior air and artillery dominance. Iran’s internal stability was also under pressure due to economic exhaustion and declining morale. International isolation deepened.

There was no breakthrough event but rather a convergence of failed offensives, external military pressure, and economic degradation that pushed Iran to accept UN Resolution 598. The decision was taken not after a decisive battlefield outcome but under cumulative pressure from multiple fronts, including internal dissent and external intervention.

Major battles of the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

Battle of Khorramshahr (1980–1982)

One of the earliest and most intense battles, Khorramshahr was attacked by Iraqi forces on 22 September 1980. After 34 days of fighting, the city fell, earning the nickname “City of Blood” due to fierce urban combat. Iranian forces recaptured it during Operation Beit ol-Moqaddas in May 1982, which marked the first major Iranian strategic success and led to Iraq’s withdrawal from most occupied territories.

Operation Ramadan (July 1982)

Following the recapture of lost territory, Iran shifted to offensive operations into Iraq. Operation Ramadan targeted Basra but resulted in high casualties and minimal gains. Over 100,000 Iranian troops participated. Despite initial progress, Iraqi minefields, armored counterattacks, and air superiority led to Iranian retreat. It marked the beginning of Iran’s costly and largely ineffective invasion strategy.

Operation Kheibar (1984)

This offensive focused on the Majnoon Islands, located in the marshlands near Basra. Iranian forces crossed difficult terrain using small boats and launched human-wave attacks. Iran temporarily held the islands, but Iraq responded with intense artillery and chemical attacks. The operation showed Iran’s commitment to high-casualty tactics, resulting in tens of thousands of dead on both sides for limited territorial gains.

Battle of the Marshes (1985–1986)

Iran attempted to outflank Iraqi defenses by exploiting the southern marshes. These battles involved amphibious operations, small boat incursions, and trench warfare in swamp terrain. Iraqi chemical weapon use intensified during these engagements. Iran gained short-term tactical advantages but failed to translate them into strategic shifts.

Operation Karbala-5 (1987)

This was Iran’s largest military operation, targeting Basra’s defensive lines. Despite deploying over 150,000 soldiers, Iranian forces failed to breach Iraq’s defensive perimeter. Iraqi air support, tanks, and chemical agents inflicted severe casualties. The failure significantly weakened Iran’s offensive capacity.

Tanker War (1984–1988)

Though not a traditional battlefield, the maritime war in the Persian Gulf impacted the global oil economy and provoked U.S. military involvement. Both sides attacked oil tankers and port facilities. Iran used naval mines, speedboats, and missile attacks. Iraq deployed Mirage F1 fighters with Exocet missiles. This maritime conflict expanded the war beyond land borders and brought global naval forces into the region.

Operation Tawakalna Ala Allah (1988)

Iraq launched a multi-phase counteroffensive, regaining lost ground in Faw Peninsula, Majnoon Islands, and southern fronts. Backed by artillery, airstrikes, and chemical weapons, Iraq defeated weakened Iranian forces and restored its territorial integrity. These operations paved the way for the ceasefire.

Each battle demonstrated the war’s attritional character, with massive resource expenditure and human cost for limited strategic shifts. The war remained stalemated for years, with victories measured in kilometers gained at enormous cost.

Was there a turning point?

There was no singular, immediate turning point in the Iran-Iraq War, but a sequence of events from 1986 to 1988 gradually shifted the balance in Iraq’s favor. The combination of battlefield reversals, growing international pressure, and internal Iranian instability formed a cumulative turning point that led to the war’s conclusion.

One critical factor was Iraq’s successful reorganization of its armed forces. From 1986, Iraq adopted combined-arms operations, improved command structures, and integrated chemical weapons more systematically into its strategy. These reforms increased operational efficiency, particularly in repelling Iranian offensives.

Meanwhile, Iran’s strategy based on mass infantry assaults began to show diminishing returns. Operation Karbala-5 in 1987, despite massive troop deployment, failed to capture Basra and inflicted catastrophic losses on Iranian forces. This failure revealed Iran’s strategic limits and exhausted its capability to wage large-scale offensives.

International dynamics accelerated the shift. Iraq improved relations with Western and Eastern bloc nations, securing access to advanced weaponry, radar systems, and aerial platforms. French Mirage F1s, Soviet MiG-25s, and Chinese Silkworm missiles enhanced Iraq’s long-range strike capabilities.

The U.S. intervention in the Persian Gulf, notably during the Tanker War, weakened Iran’s external leverage. Operation Praying Mantis in April 1988 severely damaged Iran’s naval infrastructure, signaling U.S. commitment to containing Iranian influence.

Another turning point was Operation Tawakalna Ala Allah, a sequence of Iraqi offensives between April and July 1988, which saw quick victories in Faw, Majnoon Islands, and southern Iran-Iraq front lines. These campaigns, backed by extensive artillery and chemical warfare, forced Iran into retreat and demonstrated Iraq’s regained military superiority.

By mid-1988, Iran’s economy was collapsing. Oil revenues declined due to tanker attacks, infrastructure damage, and global isolation. The civilian population was demoralized, and internal unrest increased. Iran lacked foreign allies and faced a modernized Iraqi military gaining external diplomatic support.

These combined military and political pressures compelled Iran to accept UN Resolution 598 in July 1988, marking the end of hostilities. The turning point was not a single event but a multifactorial degradation of Iran’s strategic posture combined with Iraq’s renewed military initiative.

Consequences of the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

The Iran-Iraq War left deep scars across economic, social, political, and regional dimensions. Both countries paid a massive price for a conflict that ended with no territorial gains.

Human and material losses

Estimates suggest 500,000 to 1 million people were killed, with millions more injured or displaced. Civilian infrastructure was severely damaged, particularly in cities like Khorramshahr, Basra, and Dezful. Landmine contamination remains a hazard in border areas to this day. Both nations incurred billions in economic losses, estimated at $500 billion in total damage.

Economic impact

Iran’s economy deteriorated rapidly during the war. Oil exports dropped significantly, and inflation surged beyond 30% annually. Iraq, despite receiving over $40 billion in loans from Gulf states, also suffered. Post-war, Baghdad faced major debt repayments, which later became a factor in the 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

Political and military consequences

In Iraq, Saddam Hussein used the war to centralize power further, purge rivals, and militarize society. His regime emerged politically intact but heavily indebted. The war experience also pushed Iraq toward future regional aggression.

In Iran, the conflict helped entrench the Islamic Republic, consolidating the power of the Revolutionary Guard. The war period saw the institutionalization of paramilitary organizations and the suppression of political dissent. Post-war, Iran redirected resources to rebuild industries and expand domestic military production, laying foundations for its future defense capabilities.

Chemical and unconventional warfare legacy

Iraq’s use of chemical weapons, including against civilians and Kurdish populations, set a dangerous precedent. Thousands of Iranians and Kurds suffer long-term effects from mustard gas and nerve agents. These actions contributed to global arms control reforms, including the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention.

Regional and global implications

The war reshaped Middle East alliances. Gulf monarchies strengthened their military programs and deepened ties with the West. Iran’s regional isolation influenced its long-term asymmetric warfare doctrine and support for proxy groups in Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen.

The Iran-Iraq War was not just a military conflict. It altered regional security frameworks, intensified internal repression, and left unresolved tensions that continue to shape geopolitical dynamics across the Middle East.

Back to the Wars section