An in-depth analysis of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), exploring its causes, key players, leadership, decisive moments, major battles, turning points, and lasting consequences.

The Angolan Civil War, spanning from 1975 to 2002, was a prolonged and devastating conflict that erupted immediately after Angola gained independence from Portugal. The war primarily involved two rival factions: the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). The MPLA, with support from the Soviet Union and Cuba, and UNITA, backed by the United States and South Africa, engaged in a fierce struggle for political control. The conflict was marked by intense battles, foreign interventions, and significant civilian casualties. It finally concluded in 2002 following the death of UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi, leading to a ceasefire and the integration of UNITA into the political process.

What Were the Reasons for the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

The roots of the Angolan Civil War trace back to the complex interplay of colonial history, ideological divisions, and geopolitical interests. Angola, a Portuguese colony since the 16th century, experienced a burgeoning nationalist movement in the mid-20th century, leading to the formation of several liberation groups.

Colonial Legacy and Struggle for Independence: The prolonged Portuguese colonial rule fostered deep-seated resentment among Angolans, culminating in the War of Independence (1961–1974). During this period, three primary liberation movements emerged:

- MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola): Founded in 1956, the MPLA had Marxist-Leninist inclinations and drew support from urban intellectuals and the Mbundu ethnic group.

- UNITA (União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola): Established in 1966 by Jonas Savimbi, UNITA had an anti-communist stance and garnered backing from the Ovimbundu ethnic group.

- FNLA (Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola): Formed in 1962, the FNLA was primarily supported by the Bakongo ethnic group and received backing from neighboring Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo).

The overthrow of Portugal’s Estado Novo regime during the Carnation Revolution in April 1974 accelerated decolonization efforts. The Alvor Agreement, signed in January 1975, aimed to establish a transitional government comprising the three liberation movements. However, ideological disparities and mutual distrust led to the agreement’s collapse, plunging Angola into civil war.

Ideological and Ethnic Divisions: The MPLA and UNITA, despite a shared goal of independence, were divided along ideological and ethnic lines. The MPLA’s Marxist-Leninist ideology attracted support from the Soviet Union and Cuba, while UNITA’s anti-communist position aligned it with the United States and South Africa. These ideological differences were further exacerbated by ethnic tensions, as each movement drew support from distinct ethnic groups, leading to a fragmented national identity.

Cold War Geopolitics: The global Cold War rivalry between the U.S. and the Soviet Union transformed Angola into a battleground for proxy wars. The MPLA received military and financial assistance from the Soviet bloc and Cuba, while UNITA was supported by the U.S., South Africa, and other Western allies. This external involvement intensified the conflict, as both superpowers sought to expand their spheres of influence in Africa.

Economic Interests: Angola’s rich natural resources, particularly oil and diamonds, added an economic dimension to the conflict. Control over these resources became a strategic objective for both factions, as they provided essential funding for military operations. The competition for resource-rich territories prolonged the war and attracted foreign interests seeking to exploit Angola’s wealth.

Who Was Involved in the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

The Angolan Civil War was characterized by the involvement of multiple internal factions and significant foreign interventions, each playing a pivotal role in the trajectory of the conflict.

Internal Factions:

- MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola): Led by Agostinho Neto and later by José Eduardo dos Santos, the MPLA was rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology. It drew support primarily from the Mbundu ethnic group and urban intellectuals. The MPLA established its base in the capital, Luanda, and controlled significant portions of the country’s infrastructure and resources.

- UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola): Founded by Jonas Savimbi, UNITA espoused an anti-communist stance. Its support base was predominantly among the Ovimbundu ethnic group, the largest in Angola. UNITA’s operations were mainly concentrated in the central and southern regions, where it controlled vast rural areas and resource-rich zones.

- FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola): Under the leadership of Holden Roberto, the FNLA was initially a significant player, especially in the early stages of the conflict. Supported mainly by the Bakongo ethnic group, the FNLA’s influence waned over time, particularly after military setbacks and loss of external support.

Foreign Interventions:

- Cuba: Responding to requests from the MPLA, Cuba deployed a substantial military force to Angola. At the height of its involvement, approximately 18,000 Cuban troops were stationed in the country, providing crucial support that bolstered the MPLA’s military capabilities.

- Soviet Union: The USSR supplied the MPLA with military equipment, training, and financial aid, aligning with its broader strategy of supporting socialist movements during the Cold War.

- United States: The U.S. backed UNITA as part of its Cold War policy of countering Soviet influence in Africa. Through the CIA’s covert operations, the U.S. provided financial aid, weapons, and logistical support to UNITA. The Reagan administration intensified this support under the Clark Amendment’s repeal in 1985, increasing arms shipments to Savimbi’s forces.

- South Africa: The apartheid regime in South Africa actively supported UNITA, seeing the MPLA as a regional threat. The South African Defence Force (SADF) conducted military operations in southern Angola, targeting MPLA and Cuban forces. Operation Savannah (1975-1976) marked South Africa’s initial intervention, followed by continued military engagements throughout the 1980s.

- Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo): Initially, Zaire supported the FNLA, providing arms and training to Holden Roberto’s forces. However, the FNLA’s decline led to reduced involvement.

- France and the United Kingdom: These nations had a limited role, with occasional arms deals and diplomatic maneuvering but no direct military intervention.

The war evolved into a global proxy conflict, with external players shaping the battlefield and prolonging hostilities through sustained military and financial assistance.

The Leaders of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

Agostinho Neto (1922–1979): The first president of Angola and leader of the MPLA, Neto was a staunch Marxist-Leninist who guided Angola through its early post-independence years. His administration faced immediate challenges, including civil war and economic difficulties. Neto’s policies strengthened MPLA rule but also led to political repression, notably during the 1977 attempted coup. He died in 1979, succeeded by José Eduardo dos Santos.

José Eduardo dos Santos (1942–2022): Dos Santos led the MPLA from 1979 until 2017, overseeing the war’s most intense phases. He maintained strong Soviet and Cuban ties and later pivoted to economic liberalization after the Cold War. His leadership outlasted Savimbi’s insurgency, culminating in UNITA’s defeat in 2002.

Jonas Savimbi (1934–2002): A charismatic and strategic guerrilla leader, Savimbi founded UNITA in 1966. Trained in Maoist guerrilla warfare, he led a highly effective insurgency, securing U.S. and South African support. Savimbi’s forces controlled diamond-rich territories, using revenue to finance military campaigns. His assassination in 2002 marked the end of UNITA’s armed struggle.

Holden Roberto (1923–2007): The leader of the FNLA, Roberto was instrumental in Angola’s independence struggle but lost influence as the war progressed. His faction suffered military defeats in the late 1970s, leading to its marginalization.

Fidel Castro (1926–2016): As Cuba’s leader, Castro played a crucial role in supporting the MPLA. Under his directive, Cuban military forces intervened, tipping the balance in key battles. Cuban involvement was pivotal in countering South African and UNITA offensives.

Ronald Reagan (1911–2004): The U.S. president (1981–1989) significantly increased support for UNITA, repealing the Clark Amendment and supplying advanced weapons, including Stinger missiles, to Savimbi’s forces. His administration viewed Angola as a critical Cold War battleground.

Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–2022): As Soviet leader (1985–1991), Gorbachev reduced Soviet military aid to Angola, contributing to the MPLA’s shift toward diplomacy and economic reform.

These leaders shaped the dynamics of the conflict, influencing its military, political, and diplomatic landscape.

Was There a Decisive Moment?

The war lacked a single defining battle but experienced several critical moments that shaped its trajectory.

Operation Savannah (1975–1976): South Africa’s initial invasion aimed to prevent an MPLA victory but failed due to Cuban reinforcements. This solidified Cuban involvement and prolonged the war.

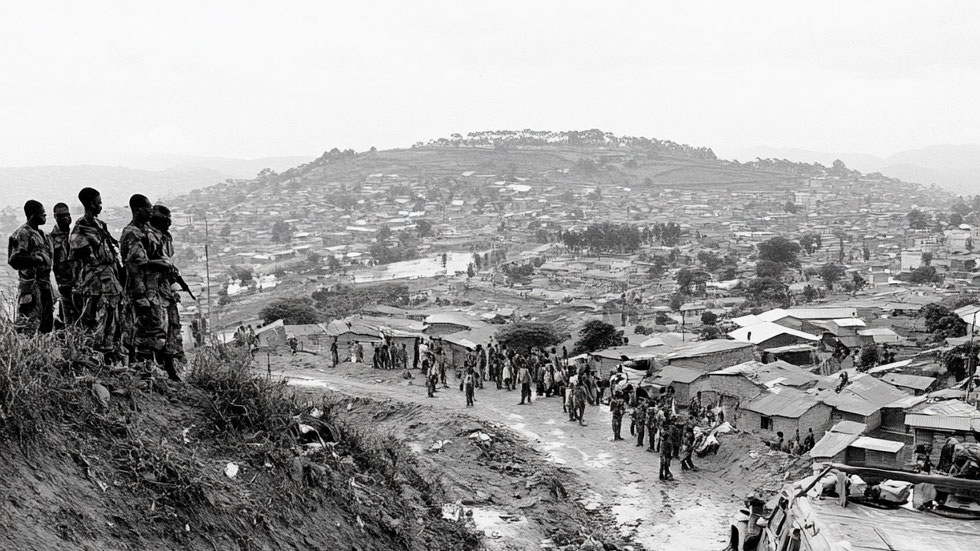

The 1987–1988 Battle of Cuito Cuanavale: One of the largest battles in African history, it pitted Cuban and MPLA forces against UNITA and South African troops. Cuban air power and Soviet-supplied artillery forced South Africa’s retreat, influencing regional diplomacy.

The 1991 Bicesse Accords: The Cold War’s end prompted U.S. and Soviet withdrawal, leading to a peace agreement. However, Savimbi rejected election results in 1992, reigniting the war.

The 1993 Siege of Huambo: UNITA’s capture of Huambo in 1993 was a major tactical win, but it failed to secure lasting control.

The 1999 Government Offensive: The MPLA launched a major offensive, capturing UNITA strongholds and cutting off diamond revenues.

Jonas Savimbi’s death (2002): Angolan government forces ambushed and killed Savimbi on February 22, 2002. This event led to UNITA’s surrender and the war’s official end.

Major Battles of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

Battle of Quifangondo (1975): The first major battle of the war, where Cuban-backed MPLA forces defeated FNLA and South African troops, ensuring MPLA’s control of Luanda.

Battle of Cuito Cuanavale (1987–1988): A prolonged six-month engagement between Cuban-MPLA forces and UNITA-South African troops. The battle ended in a strategic MPLA victory, forcing South Africa’s withdrawal.

Battle of Huambo (1993): UNITA’s biggest territorial gain, capturing Angola’s second-largest city. However, they lost it in 1994 after heavy MPLA bombardments.

Siege of Kuito (1998–1999): One of the last major battles, where MPLA forces encircled and bombarded UNITA strongholds, weakening their military capacity.

Was There a Turning Point?

While no single battle or event ended the war, the 1999–2002 MPLA offensive and Savimbi’s death marked the transition toward peace.

- 1999 Government Offensive: The MPLA, with increased oil revenues, launched large-scale operations, cutting UNITA’s supply lines and diamond trade routes.

- 2000–2001 UNITA’s Decline: UNITA lost key territories, and international support faded after the Cold War.

- 2002 Savimbi’s Death: On February 22, 2002, government troops ambushed and killed Savimbi in Moxico Province. His death left UNITA without leadership, leading to negotiations and a ceasefire in April 2002.

Consequences of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

The war’s human, political, and economic impact was profound.

- Death Toll and Displacement: Over 500,000 people died, and 4 million were displaced, creating a humanitarian crisis.

- Infrastructure Destruction: Roads, bridges, and schools were devastated, hindering economic recovery.

- Economic Impact: Angola’s oil and diamond wealth fueled the war but also exacerbated corruption. Despite post-war growth, inequality remains high.

- Political Outcome: The MPLA retained power, transitioning to a multi-party system, but José Eduardo dos Santos ruled until 2017.

- Demobilization of UNITA: UNITA became a political party in 2002, integrating into Angola’s political landscape.

- Lingering Landmines: Angola remains one of the world’s most heavily mined countries, affecting rural populations and agriculture.

The war shaped modern Angola, with economic and social challenges persisting two decades later.