A detailed look at the Cuban Revolution (1953–1959): reasons, leaders, battles, turning points, and consequences. An essential guide for understanding this conflict.

The Cuban Revolution, fought between 1953 and 1959, was a conflict led by Fidel Castro’s revolutionary movement against the government of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. The revolution arose from widespread dissatisfaction with economic inequality, corruption, and political repression. Guerrilla warfare tactics, a small group of determined fighters, and support from various sectors of Cuban society played crucial roles in the struggle. Key leaders included Fidel Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos. Significant battles, such as the attack on Moncada Barracks and the Battle of Santa Clara, marked the conflict. By January 1, 1959, Batista fled, and the revolutionaries took power. The aftermath saw sweeping changes in Cuban politics, economy, and international relations, ultimately reshaping Cuba’s trajectory.

What Were the Reasons for the Cuban Revolution?

The Cuban Revolution stemmed from deep dissatisfaction with the Batista regime. Fulgencio Batista, who seized power in a coup in 1952, was widely regarded as a corrupt and repressive leader. Under his government, economic policies favored foreign investors, particularly from the United States, while leaving much of the Cuban population in poverty. Land ownership was concentrated among a small elite, with U.S. corporations controlling significant portions of the economy, including sugar production.

Unemployment and underemployment were rampant, particularly in rural areas, where many Cubans lived in substandard conditions. Workers in these regions earned low wages and lacked basic rights. Political dissent was stifled through censorship, imprisonment, and violence. Batista relied on the military and police to maintain his authority, leading to widespread fear and resentment.

Nationalism also fueled the revolution. Many Cubans resented foreign economic domination and sought a government that prioritized Cuban sovereignty and welfare. This growing nationalist sentiment created fertile ground for revolutionaries like Fidel Castro to rally support.

The attack on Moncada Barracks in 1953, while unsuccessful, highlighted the grievances of the revolutionary movement. Castro’s “History Will Absolve Me” speech during his trial outlined a vision for land reform, improved education, and ending corruption. These ideas resonated with many Cubans, particularly students, intellectuals, and rural workers, who joined or sympathized with the movement.

By the mid-1950s, the combination of economic inequality, political repression, and growing nationalist aspirations created conditions ripe for rebellion. Castro and his supporters capitalized on these factors to build a revolutionary movement aimed at toppling Batista’s regime.

Who Was Involved in the Cuban Revolution?

The Cuban Revolution involved a diverse range of participants, from revolutionary leaders to ordinary citizens. The central opposition force was the 26th of July Movement, led by Fidel Castro. This guerrilla group was composed of fighters from varied backgrounds, including students, intellectuals, workers, and rural peasants.

Fidel Castro emerged as the leader of the revolution after organizing the failed Moncada Barracks attack in 1953. Exiled in Mexico after his imprisonment, Castro regrouped with key allies to launch a guerrilla campaign in the Sierra Maestra mountains.

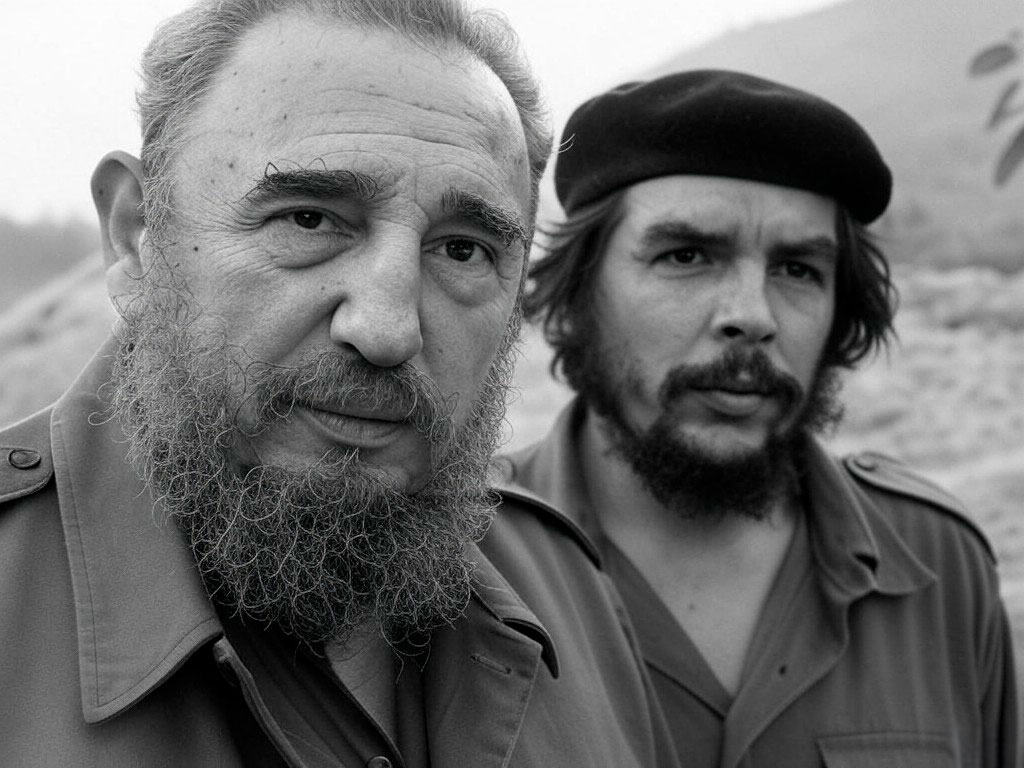

Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine physician and Marxist, became a prominent figure in the revolution. Guevara’s strategic insight and ideological commitment earned him a leadership role within the movement. Another key figure was Camilo Cienfuegos, a charismatic commander known for his ability to inspire loyalty among fighters and civilians alike.

The Batista government, on the other hand, relied on the Cuban military and police to maintain control. Batista’s forces were well-equipped but lacked morale and popular support. Many conscripts were unwilling to fight against their fellow citizens, which weakened the government’s position.

Cuban citizens played a significant role in supporting the revolution. Rural communities provided food, shelter, and intelligence to guerrilla fighters in the mountains. Urban activists engaged in sabotage, strikes, and propaganda efforts to undermine Batista’s regime. Women, including notable figures like Celia Sánchez and Haydée Santamaría, contributed as organizers, couriers, and combatants.

Internationally, the United States initially supported Batista but later imposed an arms embargo, weakening his regime further. The Soviet Union, while not directly involved during the revolution, would later play a critical role in supporting the revolutionary government.

The conflict ultimately pitted a small, ideologically driven group against a larger but demoralized and corrupt military apparatus, with civilians and international factors influencing the outcome.

The Leaders of the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution was defined by its leaders, whose strategies and ideologies guided the movement. Fidel Castro, the primary figure, emerged as a revolutionary leader following his opposition to Batista’s coup in 1952. A lawyer by training, Castro articulated the goals of the revolution through his speeches and writings. His leadership combined political vision with military tactics, allowing him to unite diverse factions under a single movement.

Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine revolutionary, became one of the most recognizable faces of the Cuban Revolution. His expertise in guerrilla warfare, combined with his Marxist ideology, shaped the strategic and ideological framework of the movement. Guevara played a key role in training fighters and leading successful campaigns, such as the Battle of Santa Clara.

Camilo Cienfuegos, a Cuban revolutionary, was known for his charisma and ability to inspire loyalty among the troops. His leadership in battles like Yaguajay demonstrated his military acumen. Unlike Guevara, Cienfuegos focused more on practical military operations than ideological matters.

Raúl Castro, Fidel’s younger brother, also held a significant leadership position. He was instrumental in organizing the movement’s logistics and securing alliances, particularly with leftist groups and international supporters.

Women played crucial roles in the revolution as well. Celia Sánchez and Haydée Santamaría were instrumental in coordinating logistics, gathering intelligence, and spreading propaganda. Their contributions ensured the continuity of the movement during critical periods.

Batista, the main antagonist, relied on a network of military officers and political allies to maintain his regime. However, his leadership was characterized by corruption and repression, which alienated much of the population.

The leadership of the Cuban Revolution was defined by its mix of military strategy, ideological commitment, and ability to inspire both fighters and civilians.

Was There a Decisive Moment?

The Cuban Revolution featured several critical moments, but no single event decisively ensured victory. However, Fidel Castro’s guerrilla warfare campaign in the Sierra Maestra mountains marked a turning point in the revolutionary struggle. After landing the Granma yacht in 1956, Castro and his fighters regrouped following a disastrous ambush that left most of their forces dead or captured. The survivors, numbering fewer than 20, established a base in the Sierra Maestra and began a sustained campaign of hit-and-run attacks.

One of the most significant moments was the Battle of La Plata in 1958, where Castro’s forces decisively defeated a government platoon. This victory boosted morale and showcased the effectiveness of guerrilla tactics. It also demonstrated that Batista’s army, while superior in numbers, struggled to operate in the rugged terrain of the mountains.

Another pivotal event was the revolutionary offensive in the second half of 1958. The Battle of Yaguajay, led by Camilo Cienfuegos, and the Battle of Santa Clara, commanded by Che Guevara, symbolized the growing strength of the revolutionary forces. These battles severely weakened Batista’s military infrastructure and morale, forcing his troops into retreat.

Urban resistance, such as sabotage and strikes, also played a decisive role. The general strike in April 1958 demonstrated the widespread support for the revolution and further isolated Batista politically and economically.

International developments contributed to Batista’s downfall. The U.S. arms embargo, imposed in March 1958, deprived Batista’s forces of critical supplies. While not a direct cause of the revolution’s success, it underscored Batista’s waning support from a key ally.

By the end of 1958, Batista’s government was crumbling under the weight of military defeats, economic instability, and international isolation. His departure on January 1, 1959, marked the culmination of these decisive moments, but the revolution’s success was the result of a prolonged and multifaceted campaign.

Major Battles of the Cuban Revolution

Several key battles defined the course of the Cuban Revolution, showcasing the strategic acumen of the revolutionary forces and the weaknesses of Batista’s army.

- The Attack on Moncada Barracks (July 26, 1953)

This initial offensive, led by Fidel Castro, was a failure militarily but pivotal in rallying support for the revolution. The attack resulted in heavy casualties for the revolutionaries, with many captured or killed. Fidel Castro was imprisoned, but his trial and “History Will Absolve Me” speech transformed the event into a rallying cry for future resistance. - The Granma Landing and Initial Skirmishes (December 1956)

The arrival of Castro, Guevara, and their group on the Granma yacht was met with immediate ambushes by Batista’s forces. Out of 82 fighters, only 12 survived. Despite this setback, the survivors regrouped in the Sierra Maestra mountains, marking the start of their guerrilla campaign. - The Battle of La Plata (July 1958)

This engagement was the first significant victory for Castro’s guerrillas. A small government platoon was encircled and forced to surrender. The win demonstrated the effectiveness of guerrilla tactics and boosted the morale of the revolutionaries. - The Battle of Yaguajay (December 1958)

Led by Camilo Cienfuegos, this battle involved a prolonged siege of a government garrison. After ten days of fighting, the defenders surrendered. This victory opened the path for revolutionary forces to advance toward central Cuba. - The Battle of Santa Clara (December 1958)

This was the final and most decisive battle of the revolution. Commanded by Che Guevara, the revolutionary forces derailed a military train carrying reinforcements and supplies, effectively crippling Batista’s defenses. Santa Clara’s capture symbolized the collapse of Batista’s regime.

Each of these battles highlighted the strategic use of terrain, popular support, and the determination of revolutionary forces. The culmination of these engagements led directly to Batista’s flight and the revolution’s success.

Was There a Turning Point?

The turning point of the Cuban Revolution can be traced to 1958, during the general offensive launched by the 26th of July Movement. By this time, the revolutionaries had shifted from defensive guerrilla warfare to a broader, coordinated campaign. The culmination of this strategy led to the Battle of Santa Clara, which effectively ended Batista’s regime.

Another critical factor was the erosion of Batista’s support. The U.S. arms embargo, implemented in March 1958, deprived his forces of vital resources. While the embargo was not explicitly designed to favor the revolutionaries, it symbolized international disapproval of Batista’s leadership. Coupled with declining morale within the Cuban military, this embargo left Batista increasingly vulnerable.

The revolutionary forces’ ability to inspire popular support also marked a turning point. By late 1958, many rural and urban Cubans actively supported the revolutionaries. This included providing supplies, intelligence, and manpower, which enabled the 26th of July Movement to expand its influence beyond the Sierra Maestra.

The general strike of April 1958 demonstrated the growing momentum of the revolutionary movement. It paralyzed key sectors of the Cuban economy, further weakening Batista’s grip on power. This strike, coupled with the military successes in Yaguajay and Santa Clara, showed that the revolution had shifted from a localized uprising to a nationwide movement.

The turning point was not a single event but rather a series of interrelated developments that, by late 1958, made Batista’s downfall inevitable. These included military defeats, international isolation, and widespread public discontent.

Consequences of the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution had profound political, economic, and social consequences, both domestically and internationally.

Domestically, the revolution led to the establishment of a new government under Fidel Castro. One of its first acts was the nationalization of industries, including sugar production and foreign-owned businesses, primarily U.S.-controlled corporations. This move redistributed wealth but also strained relations with the United States, culminating in the U.S. trade embargo that persists to this day.

Agrarian reform was another cornerstone of the new regime. The government redistributed land to peasants, aiming to address rural poverty and inequality. While these reforms improved conditions for some, they also disrupted traditional economic structures.

The revolution transformed Cuba’s healthcare and education systems. Universal healthcare and free education became government priorities, significantly improving literacy rates and life expectancy. However, economic policies, such as central planning, created inefficiencies and shortages that persist in modern Cuba.

Internationally, the Cuban Revolution shifted Cold War dynamics. Cuba aligned with the Soviet Union, becoming a socialist state just 90 miles from the United States. This alliance led to key events like the Bay of Pigs Invasion (1961) and the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962). These crises highlighted Cuba’s strategic importance and the global repercussions of its revolution.

Cuba’s revolutionary model also inspired leftist movements across Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Figures like Che Guevara became symbols of resistance against imperialism and capitalism. However, the exportation of revolutionary ideology often provoked violent conflicts in these regions.

The revolution also entrenched authoritarian rule in Cuba. Political dissent was suppressed, and opposition parties were banned. While the government achieved significant social reforms, it did so at the cost of individual freedoms.

The Cuban Revolution remains a pivotal moment in history, with its effects still felt today in both Cuba’s domestic policies and its role on the global stage.

Back to the Wars section