A technical overview of the Mexican Revolution, examining its causes, major players, decisive battles, and transformative impact on Mexican society and politics.

Quick Read

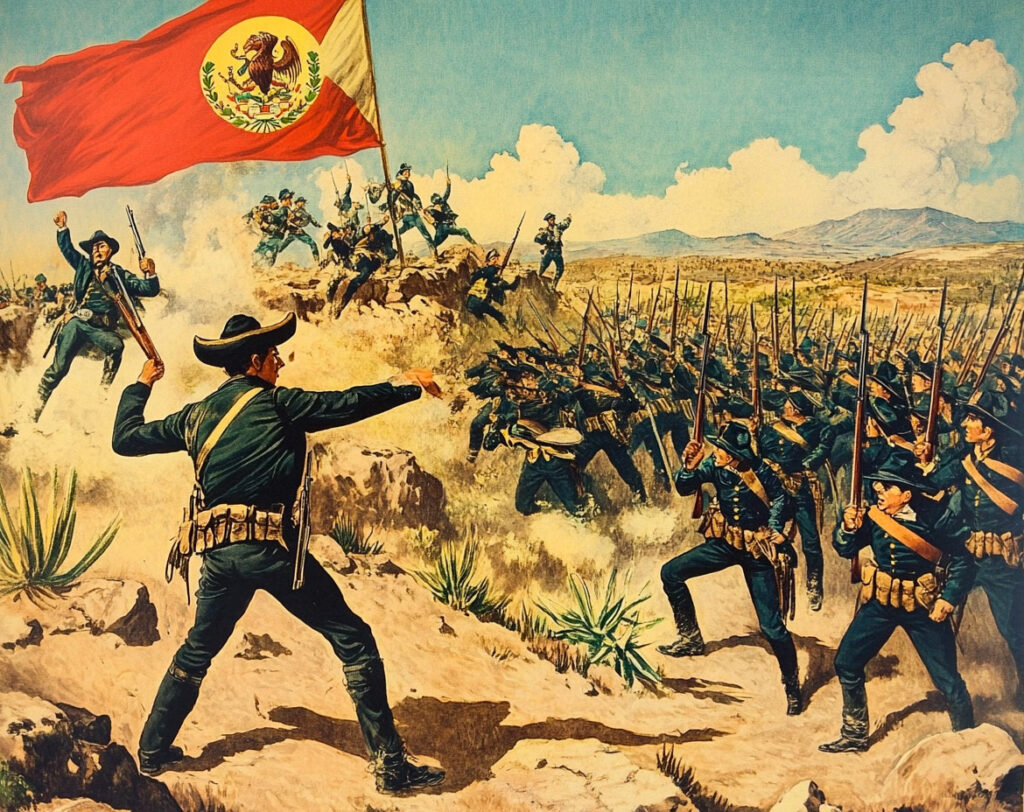

The Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) was a complex and multi-faceted conflict that fundamentally reshaped Mexican society and politics. Sparked by widespread dissatisfaction with the prolonged dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, the revolution began as a movement to overthrow him but evolved into a struggle for land reform, labor rights, and social justice. The revolution pitted diverse factions against each other, including peasant leaders like Emiliano Zapata, regional warlords like Pancho Villa, and political reformers like Francisco Madero. Despite significant infighting and ideological differences, the revolution ultimately resulted in the establishment of a new constitution in 1917, which promised land reform and labor protections. By 1920, a factionalized government remained, but the social and economic foundations of Mexico had irrevocably changed. The revolution marked Mexico’s transition from an oligarchic regime to a state with promises of social rights and reforms for its citizens.

What Were the Reasons for the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

The Mexican Revolution was primarily a response to the authoritarian rule of Porfirio Díaz, who governed Mexico for over 30 years. During his presidency, known as the Porfiriato, Díaz implemented policies that promoted economic growth, but these benefits were not equitably distributed. While Díaz modernized infrastructure and attracted foreign investment, his policies favored wealthy landowners, foreign businesses, and elite interests, leading to widespread poverty among peasants and workers.

Under Díaz, large portions of Mexican land were concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy families and foreign corporations. The encomienda system allowed these elites to seize land traditionally used by indigenous communities, forcing many peasants to work as tenant farmers or laborers on large estates. This land dispossession fueled resentment among the rural population, as small farmers struggled to survive under exploitative conditions.

Political repression also characterized the Díaz regime. Díaz restricted freedom of the press, suppressed political dissent, and maintained power through a network of loyal caudillos and military force. As a result, political opposition faced persecution or exile, leaving little space for democratic participation.

Social inequality and political exclusion were compounded by the growing influence of foreign capital. American and European investors controlled key sectors, including mining, oil, and railways. While these investments contributed to economic growth, they intensified resentment, as profits largely benefited foreign companies and a small Mexican elite.

In 1910, Francisco Madero, a wealthy but reform-minded landowner, challenged Díaz’s rule by calling for free elections. Madero’s Plan of San Luis Potosí called for an uprising against Díaz, promising land reform and political freedom. This manifesto resonated with various disaffected groups, including peasants, workers, and middle-class reformers.

The revolution that followed was not only a fight to remove Díaz but also an expression of broader demands for social justice, land reform, and democratic governance. These unresolved issues led to a prolonged and violent struggle that would ultimately reshape Mexico’s political and social landscape.

Who Was Involved in the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

The Mexican Revolution saw diverse factions and social groups rallying against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz and vying for control over the country’s future. The primary groups involved were peasant militias, regional warlords, reformist elites, and eventually the Constitutionalist faction led by Venustiano Carranza.

The revolution was initially led by Francisco Madero, a wealthy landowner who opposed Díaz’s rule. Madero’s call for democracy and reform attracted widespread support among discontented peasants and workers. Madero’s movement inspired the first wave of armed resistance, with different factions rallying around their specific goals, from political reform to land redistribution.

Among the most notable peasant factions were those led by Emiliano Zapata in the south. Zapata’s forces, known as the Zapatistas, represented the interests of rural communities. His Plan of Ayala called for land redistribution to return land to indigenous and peasant communities. Zapata’s followers engaged in guerrilla warfare, seizing haciendas and redistributing land, embodying the agrarian ideals of the revolution.

In the north, Pancho Villa emerged as a charismatic leader. Villa led the División del Norte, a formidable fighting force composed largely of former cowboys, laborers, and disenfranchised individuals. Villa’s army engaged in major battles against government forces and controlled large parts of northern Mexico. Villa’s reputation as a social reformer and Robin Hood-like figure endeared him to the working class, although his goals were often at odds with other revolutionary leaders.

The Constitutionalists, led by Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón, represented a more moderate faction seeking to establish a constitutional government and modernize Mexico. Supported by urban middle-class reformers and some elements of the military, the Constitutionalists eventually gained power, especially after Victoriano Huerta’s brief dictatorship was ousted.

Foreign powers, particularly the United States, also influenced the revolution. The U.S. intervened at various points, supporting Carranza’s forces against Villa and Zapata. The involvement of these diverse factions with conflicting goals led to a protracted and violent conflict that continued until Carranza’s faction solidified power in the 1920s.

The Leaders of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

The Mexican Revolution was shaped by influential leaders, each representing distinct factions and ideologies. These figures played critical roles in directing the course of the conflict and defining its objectives.

Francisco Madero was the initial leader whose reformist ideals sparked the revolution. He issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí, calling for an uprising against Porfirio Díaz and advocating for democratic reforms. Madero’s presidency, however, faced challenges, as his moderate stance on land reform disappointed both radical and conservative factions. He was eventually overthrown by Victoriano Huerta in 1913, which led to further division.

Emiliano Zapata, a peasant leader from Morelos, emerged as the face of agrarian reform. His Plan of Ayala demanded the return of communal lands to indigenous villages and outlined a vision of social justice centered on land redistribution. Zapata’s forces, known as Zapatistas, used guerrilla tactics to fight for local autonomy. Zapata’s deep-rooted connection to rural communities made him a powerful symbol of the agrarian struggle.

Pancho Villa, leader of the División del Norte in northern Mexico, was another prominent revolutionary figure. Villa’s charismatic leadership attracted followers from diverse social backgrounds. His military skills and effective tactics allowed him to gain control of large territories. Villa’s reputation as a champion of the poor and working-class, combined with his personal charisma, made him a complex but significant revolutionary leader.

Venustiano Carranza represented the Constitutionalist faction that sought to establish a centralized government. Carranza eventually gained support from the United States, aiding his victory over Villa and Zapata’s forces. As president, Carranza oversaw the drafting of the Constitution of 1917, which included progressive reforms on labor rights and land redistribution.

Álvaro Obregón, a key ally of Carranza, was known for his strategic prowess in battle. He played a decisive role in defeating Villa’s forces and later challenged Carranza’s authority, becoming president himself in 1920. Obregón’s pragmatic approach allowed him to consolidate power and implement parts of the revolutionary agenda, establishing a degree of stability in post-revolutionary Mexico.

Was There a Decisive Moment?

The Mexican Revolution lacked a singular, decisive moment that defined its course, as it was a protracted struggle with multiple shifting alliances and ongoing regional conflicts. However, the assassination of Francisco Madero in 1913 was a pivotal event that deepened divisions among revolutionary factions and reshaped the movement.

Madero’s assassination marked a significant turning point. Madero had united various factions under his call for democratic reform, but his death at the hands of Victoriano Huerta shattered the coalition. Huerta, a military general with conservative backing, sought to restore a more authoritarian rule, sparking widespread resistance from former Madero supporters and igniting the second phase of the revolution.

The Constitutionalist faction led by Venustiano Carranza gained momentum following Madero’s death. Carranza issued the Plan of Guadalupe, rejecting Huerta’s government and calling for a return to constitutional rule. This plan garnered support from a broad coalition, including urban reformers, moderate revolutionaries, and parts of the military. Carranza’s campaign against Huerta’s forces drew support from Álvaro Obregón, whose military strategy helped turn the tide in favor of the Constitutionalists.

The capture of Mexico City by Carranza’s forces in 1914 and Huerta’s subsequent resignation marked the collapse of Huerta’s regime. However, the revolution did not end there. The power vacuum led to further conflicts among revolutionary leaders, with Carranza, Villa, and Zapata vying for control over the new government’s direction.

Although Madero’s assassination was a critical event, the revolution remained fragmented due to ongoing ideological differences. The conflict would continue, marked by major battles and shifting alliances, until Carranza’s victory established a semblance of centralized power.

Major Battles of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

The Mexican Revolution involved numerous battles and engagements, each shaping the outcome of the prolonged conflict. Some key battles are outlined below:

- Battle of Ciudad Juárez (1911): The Battle of Ciudad Juárez was one of the first significant victories for Madero’s forces. Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco led the assault on Ciudad Juárez, capturing the city from federal forces loyal to Díaz. This victory compelled Díaz to enter negotiations, leading to his resignation and the eventual end of his rule.

- Ten Tragic Days (La Decena Trágica) (1913): This period marked one of the bloodiest episodes of the revolution, as forces loyal to Victoriano Huerta revolted against Madero in Mexico City. Intense fighting lasted for ten days, culminating in the capture and execution of Madero. Huerta’s coup d’état deepened factional divides and intensified the conflict.

- Battle of Torreón (1913): The Battle of Torreón was a key engagement between Huerta’s forces and the Constitutionalist army led by Pancho Villa. Villa’s victory at Torreón significantly weakened Huerta’s control in northern Mexico. Torreón became a symbol of the growing strength of revolutionary forces against Huerta’s regime.

- Battle of Zacatecas (1914): Considered one of the most important battles, the Battle of Zacatecas was a decisive victory for Villa’s forces. The battle resulted in heavy casualties for Huerta’s army and effectively cut off Huerta’s supply lines. Villa’s success at Zacatecas forced Huerta to abandon his position, leading to his resignation and the fall of his regime.

- Battle of Celaya (1915): The Battle of Celaya saw Álvaro Obregón facing Villa in a significant confrontation between revolutionary factions. Obregón, representing Carranza’s Constitutionalists, implemented innovative trench warfare tactics and artillery strategies. His victory over Villa’s forces marked a turning point in favor of Carranza, consolidating his power in the revolutionary government.

- Occupation of Mexico City (1914): After Huerta’s fall, Carranza’s Constitutionalists entered Mexico City, signaling a shift in power. However, the city’s occupation by different factions continued as Villa and Zapata briefly seized control, underscoring the revolution’s complex nature and ongoing struggle for dominance.

Was There a Turning Point?

The Battle of Celaya in 1915 is often seen as the turning point of the Mexican Revolution. This confrontation between Pancho Villa’s División del Norte and Álvaro Obregón’s Constitutionalist forces marked a shift in military momentum toward Venustiano Carranza’s faction.

Villa’s forces had achieved significant victories and were considered a formidable threat. However, the Battle of Celaya exposed the limitations of Villa’s strategies. Obregón, known for his military acumen, used trench warfare and advanced artillery tactics to counter Villa’s charges. This approach was unconventional in Mexican warfare but proved highly effective. Obregón’s forces successfully repelled Villa’s attacks, inflicting heavy casualties.

The defeat at Celaya weakened Villa’s forces and curtailed his influence. Following this battle, Villa’s control over northern Mexico diminished, and Carranza’s Constitutionalists were able to assert greater authority. The battle also illustrated a shift toward more modernized warfare tactics, which would characterize later conflicts in Mexico.

With Villa’s power significantly reduced, Carranza’s faction consolidated its position, eventually leading to Carranza’s presidency. The Battle of Celaya thus marked a decisive point, not only in weakening Villa but also in establishing Carranza’s Constitutionalists as the dominant faction in the revolutionary landscape.

Consequences of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

The Mexican Revolution led to profound social, political, and economic changes. One of the most significant outcomes was the creation of the Constitution of 1917, which introduced a framework for land reform, labor rights, and education. Articles such as Article 27 addressed land ownership, granting the state authority over natural resources and paving the way for land redistribution to peasants. Article 123 established labor protections, including an eight-hour workday, wage regulations, and rights to unionize.

The revolution marked a shift in Mexico’s political structure, as the old elite system was replaced by a more centralized government committed to social reform. Venustiano Carranza’s rise to power as president symbolized this transformation, although the new government faced challenges in implementing reforms amid continued resistance from regional factions.

Socially, the revolution empowered indigenous and peasant communities by advocating for their rights and representation. Figures like Emiliano Zapata became symbols of agrarian justice, and the Zapatista movement left a lasting legacy in the fight for land rights.

The economic impact was substantial, as the conflict disrupted agriculture, mining, and industry. Foreign-owned businesses, especially in oil and railways, saw increased regulation under the new government. The revolution’s emphasis on Mexican sovereignty over resources laid the groundwork for later nationalization policies, including the expropriation of the oil industry in 1938.

The revolution also influenced Mexican culture and identity, leading to a renaissance in art, literature, and public expression. Revolutionary ideals became integral to Mexican nationalism, inspiring artists like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo to depict themes of social justice and indigenous heritage.

Internationally, the Mexican Revolution was one of the first major social revolutions of the 20th century. Its success in addressing issues of land and labor influenced later movements in Latin America. The revolution set a precedent for state-led social reform and inspired political thought in the region.

The Mexican Revolution ultimately transformed Mexico into a nation with stronger national identity and commitment to social rights, albeit with ongoing challenges in realizing the ideals set forth during the conflict.

Back to the Wars section