A comprehensive and factual breakdown of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989), from causes to consequences, major battles, and turning points.

The Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989) was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Afghan insurgents known as the Mujahideen. It began in December 1979 when the Soviet Army invaded Afghanistan to support the pro-communist government of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) against growing opposition. The Mujahideen, backed by the United States, Pakistan, China, Iran, and others, used guerrilla tactics and took advantage of Afghanistan’s rugged terrain. The war turned into a prolonged and costly campaign. Over 1 million Afghans died, and around 15,000 Soviet soldiers were killed. The Soviet withdrawal began in May 1988 and concluded in February 1989. The conflict significantly weakened the Soviet Union’s economy and morale and played a role in its eventual collapse in 1991. Afghanistan was left in chaos and civil war.

What were the reasons for the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)

The main reason for the Soviet invasion was to support the communist government in Afghanistan, led by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The PDPA came to power in April 1978 after a coup known as the Saur Revolution, overthrowing President Mohammed Daoud Khan. The new regime initiated radical reforms, including land redistribution, women’s rights, and secular education, which triggered strong opposition from rural tribes, Islamic clerics, and traditional power structures.

By late 1979, the situation in Afghanistan had become unstable. Internal divisions within the PDPA leadership and a growing Islamist insurgency created concerns for the Soviet Union, which considered Afghanistan a strategic buffer zone on its southern border. Soviet leaders feared the collapse of a friendly government and the spread of Islamic extremism into Soviet Central Asia.

Another key factor was geopolitical competition. The Soviet Union wanted to maintain its influence in South and Central Asia, particularly in light of the growing US-Pakistani ties and the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which had altered the balance of power in the region. Afghanistan was viewed as a potential client state, and Moscow wanted to secure a stable pro-Soviet regime.

The Soviet Union also feared the fragmentation of the PDPA, especially under the leadership of Hafizullah Amin, whose rule was increasingly seen as erratic and unreliable. Intelligence reports indicated Amin might open dialogue with the United States, which alarmed Soviet policymakers.

On December 24, 1979, the Soviet Army crossed into Afghanistan, assassinated Amin, and installed Babrak Karmal, a pro-Moscow PDPA figure. The official narrative was that the Soviet Union had responded to a request for military assistance, but the operation was pre-planned and strategically motivated.

Who was involved in the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)

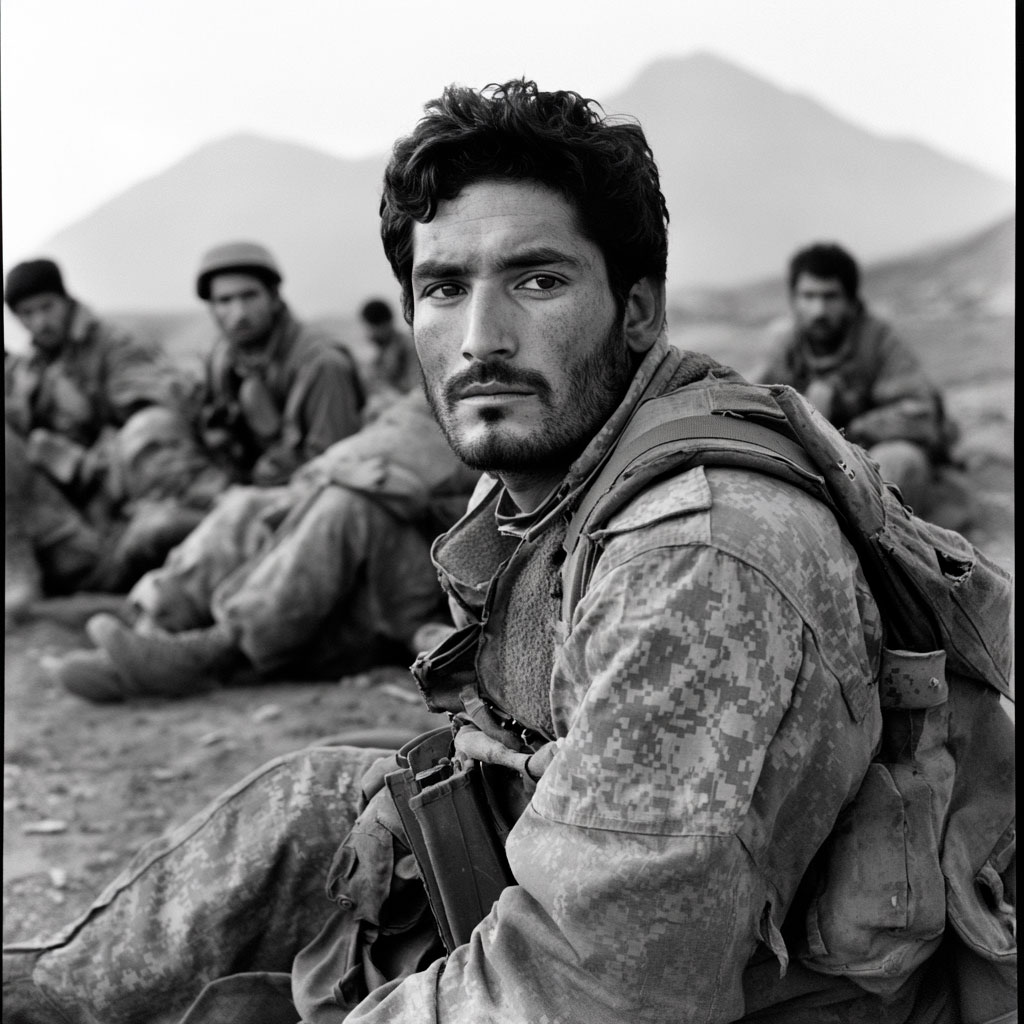

The war involved multiple actors both directly and indirectly. On one side stood the Soviet Union, with over 620,000 troops deployed in total over the decade. The bulk of the forces came from the 40th Army, under Soviet Ground Forces Command. Support units included airborne troops, special forces (Spetsnaz), air force squadrons, and logistical divisions.

On the Afghan side, the pro-Soviet government forces were the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan Army (DRA). Despite Soviet training and equipment, the DRA faced serious issues: low morale, frequent defections, and weak leadership limited its effectiveness. At its peak, the DRA had about 170,000 troops, though most were undertrained and poorly equipped.

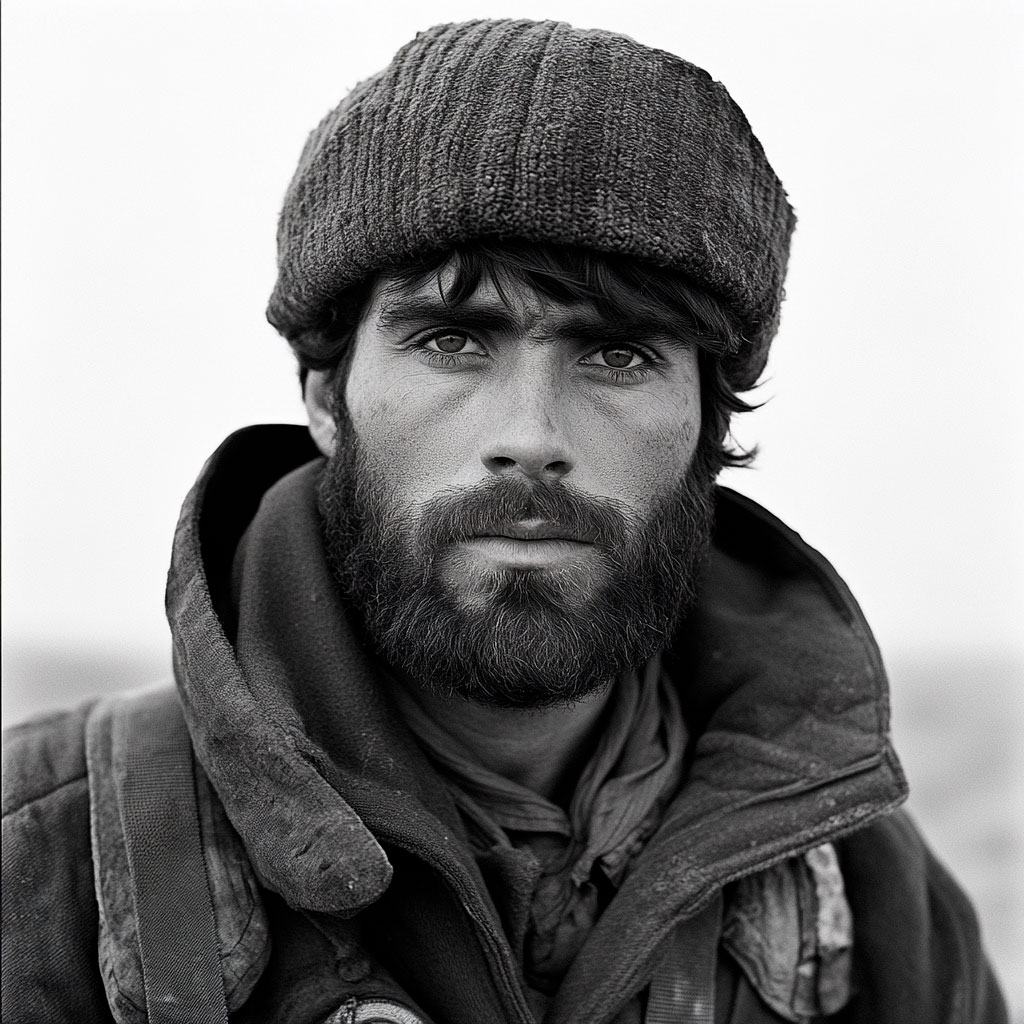

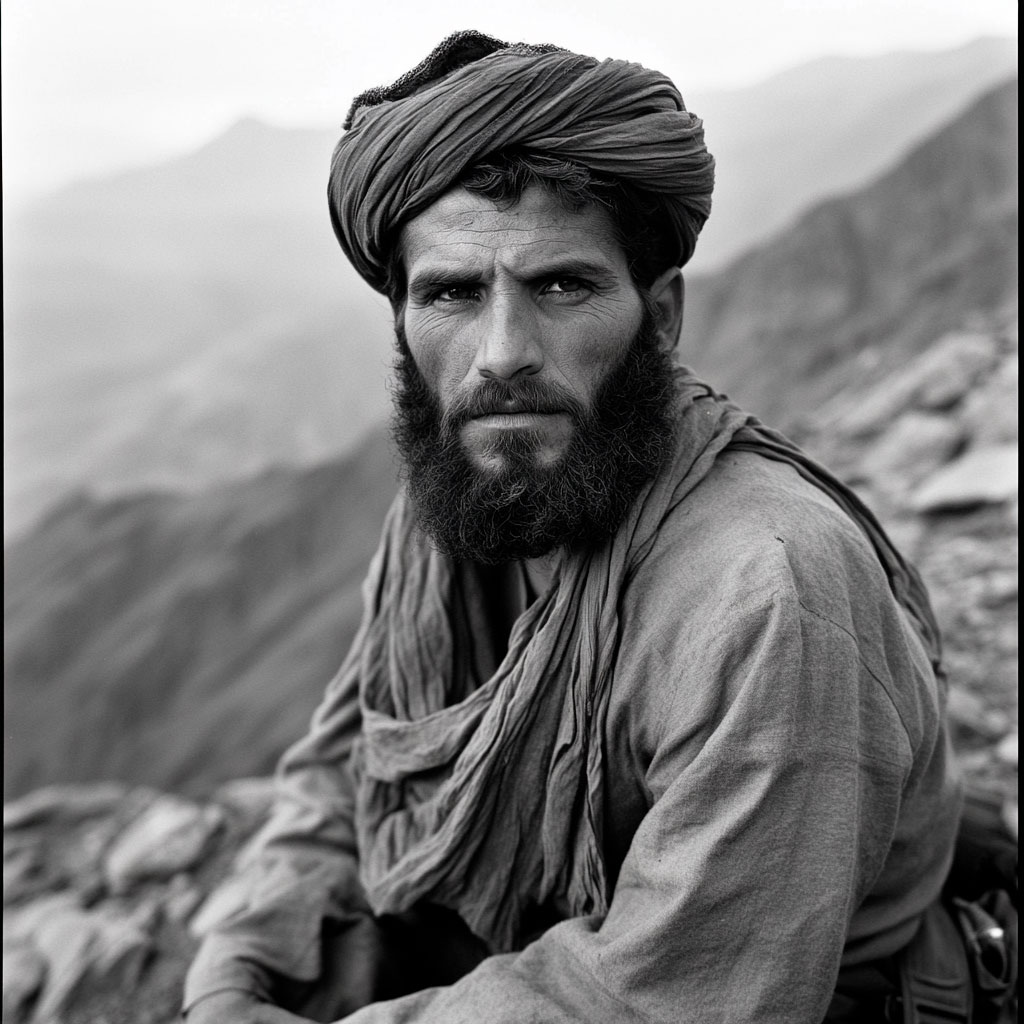

Opposing them was the Mujahideen, a fragmented but highly motivated force composed of various ethnic groups: Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras. These guerrilla fighters were organized under several factions, including Hezb-e Islami (Gulbuddin Hekmatyar), Jamiat-e Islami (Burhanuddin Rabbani), and Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami. These groups operated independently, often along tribal or ideological lines.

Foreign involvement was significant. The United States, through the CIA’s Operation Cyclone, provided billions of dollars in weapons, training, and logistical support to the Mujahideen. Most of this aid was funneled through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), which had substantial control over which groups received support.

Pakistan played a dual role: it offered sanctuary to Mujahideen fighters and training camps on its territory. Over 5 million Afghan refugees crossed into Pakistan during the war. Saudi Arabia matched US funding and promoted the Salafist ideology among fighters. China supplied arms and light weaponry, motivated by its own tensions with the Soviet Union.

Other regional players, like Iran, supported Shia factions, although its involvement remained limited compared to that of the Sunni-aligned countries.

The conflict became a proxy war under the larger umbrella of the Cold War, drawing in diverse international actors with competing strategic interests.

The leaders of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)

The war involved several key political and military leaders on both sides. In the Soviet Union, leadership changed over time, affecting policy and strategy. Leonid Brezhnev, the General Secretary at the start of the war, authorized the intervention in 1979. He died in 1982, and was followed by Yuri Andropov (1982–1984), then Konstantin Chernenko (1984–1985), and finally Mikhail Gorbachev (1985–1991), who initiated the withdrawal.

Gorbachev called the war a “bleeding wound”, and under his leadership, the Soviet Union sought a way out through diplomacy and disengagement.

On the military side, several Soviet generals commanded the 40th Army, including General Boris Gromov, who led the final withdrawal in February 1989. Other figures included General Ivan Pavlovsky, Marshal Sergei Sokolov, and General Valentin Varennikov. These officers had to adapt to mountain warfare, guerrilla ambushes, and supply line threats, which were unfamiliar to a conventionally trained army.

In Afghanistan, the PDPA leadership changed hands several times. Hafizullah Amin, who came to power in 1979, was killed during the Soviet invasion. He was replaced by Babrak Karmal, a Moscow ally. Karmal held power from 1979 to 1986, but failed to gain popular support. In 1986, he was replaced by Mohammad Najibullah, head of the secret police (KHAD). Najibullah launched a “national reconciliation policy”, which included amnesties, tribal outreach, and attempts at negotiated settlements.

On the Mujahideen side, leadership was fragmented. Notable figures included Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, known for his hardline stance and ISI ties; Ahmad Shah Massoud, who led the Northern Alliance and became one of the most tactically effective commanders; and Burhanuddin Rabbani, a political and religious leader. Their influence often depended more on tribal loyalty and foreign support than on centralized coordination.

The war’s leadership was marked by frequent transitions, internal factionalism, and limited coordination among resistance forces, which complicated efforts on both sides.

Was there a decisive moment?

There was no single decisive moment in the Soviet-Afghan War, but several key developments significantly shaped the outcome. One major turning point was the introduction of US-supplied FIM-92 Stinger missiles in 1986. These shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles radically altered the balance of power by allowing the Mujahideen to shoot down Soviet Mi-24 Hind helicopters and Su-25 ground attack aircraft, which had previously dominated the battlefield.

Before the Stingers, Soviet air superiority had been critical in supporting ground operations and disrupting Mujahideen logistics. The sudden vulnerability of aircraft forced changes in Soviet tactics, reduced air coverage, and increased operational costs.

Another important event was Gorbachev’s rise to power in 1985. He immediately questioned the war’s viability and pushed for diplomatic solutions, viewing the war as politically and economically unsustainable. In 1986, he publicly declared that the war must end soon, setting the stage for negotiations.

The Geneva Accords of April 1988, signed by Afghanistan, Pakistan, the US, and the Soviet Union, established the legal basis for withdrawal. Although the Mujahideen were not part of the negotiations, the agreement led to a timetable for Soviet troop exit, beginning in May 1988.

On the battlefield, Soviet offensives such as Operation Magistral (1987) attempted to break Mujahideen strongholds and demonstrate control, but these operations yielded limited long-term effects. The Soviets could secure areas temporarily, but failed to hold territory once they withdrew.

In summary, the Stinger missile deployment, Gorbachev’s policy shift, and the Geneva Accords represent the most impactful moments in the conflict. However, the war remained a slow attritional struggle, where small gains were constantly undermined by losses in morale, rising costs, and political pressure.

Major battles of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)

The Soviet-Afghan War was marked by numerous battles, many of which were not conventional engagements but prolonged counterinsurgency operations in mountainous terrain. Most Soviet missions aimed at clearing areas, destroying Mujahideen infrastructure, and securing supply routes. The following are the most significant military operations during the war.

Battle of Kabul (1979–1989)

The capital city Kabul remained under Soviet control throughout the war, but it was constantly attacked by Mujahideen rocket fire, sabotage, and infiltration. Urban insurgency forced the Soviets and the DRA to fortify the city heavily, using armored units, checkpoints, and militia patrols. The protracted defense of Kabul drained manpower and equipment, and civilian casualties were substantial.

Operation Storm-333 (December 27, 1979)

This was the initial assault by Soviet special forces to eliminate President Hafizullah Amin and seize the Tajbeg Palace. Alpha Group and Vympel units conducted a coordinated raid supported by regular infantry and airborne units. The operation was successful in assassinating Amin and installing Babrak Karmal, marking the start of direct Soviet intervention.

Panjshir Valley Campaigns (1980–1985)

The Panjshir Valley, under the control of Ahmad Shah Massoud, was a repeated target. The Soviets launched nine major offensives to dislodge Massoud. These included Operation Panjshir I to IX, with the largest being Operation Panjshir V (1982), involving over 12,000 Soviet and DRA troops. Despite airpower and artillery, the Soviets failed to maintain control. Massoud’s hit-and-run tactics, local intelligence networks, and tunnel systems gave him strategic advantage.

Battle of Khost (1987–1988)

The city of Khost, near the Pakistan border, was under a long Mujahideen siege. In Operation Magistral (1987), Soviet forces conducted a massive effort to break the blockade, deploying over 15,000 troops, tanks, and air support. The road to Gardez-Khost was reopened temporarily. The operation involved brutal mountain fighting, helicopter assaults, and heavy casualties. Once the Soviets left, the Mujahideen quickly reimposed pressure on Khost.

Operation Trap (1983)

In Herat Province, a Spetsnaz operation targeted Mujahideen supply routes and weapons caches along the Iranian border. The Soviets deployed airborne regiments and reconnaissance teams, but were ambushed during withdrawal, suffering high losses. The terrain favored the insurgents, and Soviet forces struggled to maintain long-range missions in such areas.

Operation Typhoon (1986)

This lesser-known campaign in Kunar Province targeted Mujahideen camps and aimed to disrupt cross-border movement from Pakistan. It involved coordinated air strikes and artillery bombardments, but Mujahideen tactics of rapid dispersal and infiltration nullified the impact. Soviet units withdrew after temporary success, unable to secure permanent control.

Throughout these battles, logistics, terrain, and guerrilla tactics played larger roles than firepower. Soviet control was temporary in most areas, and Mujahideen forces reoccupied zones as soon as troops left. The high cost of attrition warfare without clear territorial gains weakened the overall strategic objectives of the Soviet Union.

Was there a turning point?

The war experienced a slow shift in momentum rather than a single sharp turning point. However, the mid-1980s saw a strategic decline in Soviet effectiveness and a rise in Mujahideen capabilities.

The arrival of the Stinger missile in 1986 was a critical operational development. Soviet air power, previously unchallenged, became less effective and more vulnerable. The loss rates for Mi-24 helicopters and transport aircraft increased. This impacted troop mobility, aerial reconnaissance, and supply missions.

At the same time, Ahmad Shah Massoud’s forces began to consolidate control in northern Afghanistan, setting up civil administration, local courts, and supply logistics. His structure allowed greater resilience and coordination, in contrast to other Mujahideen factions. This shift from fragmented insurgency to organized territorial resistance made Soviet gains increasingly temporary.

Internally, the Soviet Union’s political leadership shifted under Gorbachev. He publicly acknowledged the war’s costliness and its negative impact on economic performance and international image. Soviet casualties had passed 15,000 dead, and tens of thousands wounded. The domestic population became increasingly hostile to the conflict, as did segments of the Communist Party.

International pressure increased. The United Nations General Assembly passed repeated resolutions calling for Soviet withdrawal. Media coverage and diplomatic isolation grew. Meanwhile, US and Saudi funding for the Mujahideen rose, delivering not only weapons but training via ISI and CIA programs in Pakistan.

By 1987, the Soviets began planning a structured withdrawal, signaled by a de-escalation of offensive operations and a shift toward fortified defense positions near major cities. The Geneva Accords (1988) confirmed this trend.

Although not a single moment, this series of military, political, and international changes between 1985–1988 marked a clear deterioration of Soviet position, and a transition toward disengagement.

Consequences of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)

The Soviet-Afghan War produced extensive long-term consequences, both for Afghanistan and for the Soviet Union. These effects were political, economic, military, and social.

Impact on Afghanistan

The war left Afghanistan devastated. More than 1 million civilians were killed, and over 5 million Afghans fled as refugees, primarily to Pakistan and Iran. Another 2 million people were internally displaced. Entire villages were destroyed, agricultural infrastructure was ruined, and the economy collapsed. Key sectors, including irrigation, livestock, and trade, suffered severe losses.

The use of landmines and aerial bombardments caused widespread contamination of farmland. As of 1989, millions of unexploded ordnances remained across the countryside, causing injuries long after combat ended.

Socially, the war fragmented tribal and ethnic cohesion, contributing to power vacuums later filled by warlords and militias. The PDPA regime, kept in power by Soviet support, was unable to survive after the Soviet withdrawal. By 1992, it collapsed, and Afghanistan entered a period of civil war, eventually leading to the rise of the Taliban by 1996.

Impact on the Soviet Union

The war exposed the limits of Soviet military capabilities. The death toll of over 15,000 soldiers, over 35,000 wounded, and an estimated 300,000 casualties including psychological trauma, eroded public confidence. The cost of the war, estimated at 8.2 billion rubles annually, placed a significant burden on the Soviet economy, already struggling with stagnation.

The conflict contributed to a broader crisis of legitimacy for the Soviet regime. Discontent among military families, students, and veterans (Afghantsy) increased. The war’s unpopularity fueled reformist demands, weakening the Communist Party’s internal cohesion.

Military doctrine also changed. The war discredited large-scale conventional operations in asymmetric conflicts and highlighted the need for mobility, intelligence, and counter-insurgency tactics. These lessons influenced post-1991 Russian military thinking.

Internationally, the Soviet Union suffered diplomatic losses. The war damaged its image in the Non-Aligned Movement, gave momentum to US strategic influence in the region, and strengthened ties between the US, Pakistan, and China.

The Soviet withdrawal became a symbol of strategic failure, affecting foreign policy calculations in Eastern Europe and contributing indirectly to political change in the Warsaw Pact states. It was one of many factors that led to the dissolution of the USSR in 1991.

The war reshaped Afghanistan and weakened the Soviet system. Its aftershocks are still visible in global geopolitics today.

Back to the Wars section