Arc wants to drop military equipment from orbit in less than an hour. Promise, real uses, physical limitations, and cost.

Summary

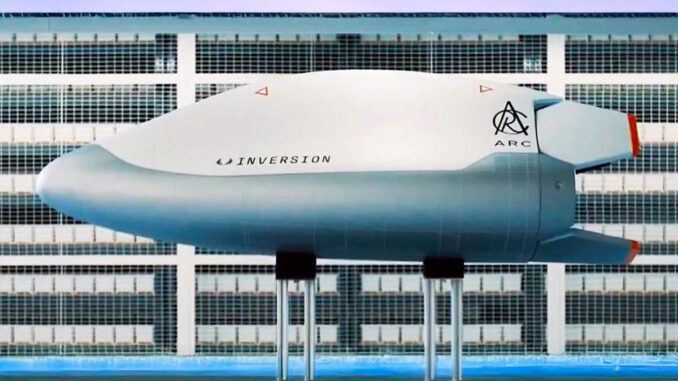

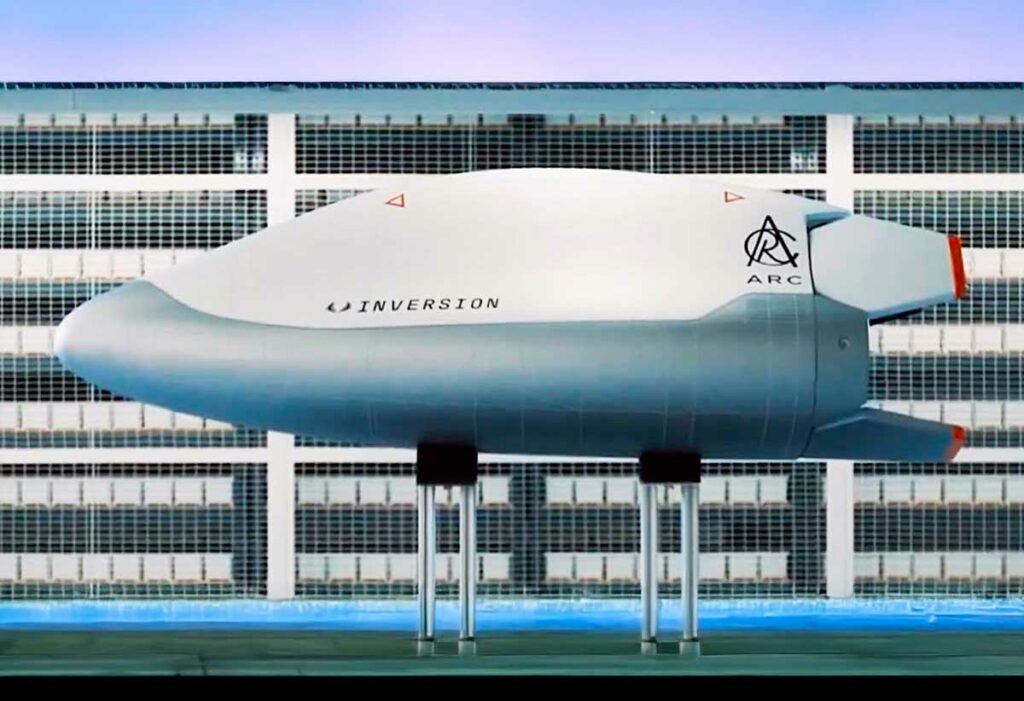

Arc, developed by Inversion Space, has a goal that is simple to state but difficult to achieve: to deliver military supplies on demand, from orbit, to almost anywhere on Earth in less than an hour. The concept is based on small vehicles, preloaded and stored in low orbit, capable of deorbiting on command, crossing the atmosphere, and then landing with precision on a variety of surfaces. On paper, it is a response to the logistical challenges in contested areas: delays, denied access, anti-aircraft threats, weather, and road sabotage. In reality, the technical feasibility exists, but the operational value will depend on the cost per mission, the final precision, the recovery capacity, and above all, the “right” type of payload: compact, critical, and immediately usable. Arc could complement, not replace, conventional tactical transport.

The promise of logistics that no longer negotiates access

In modern conflict, transport is often more decisive than weaponry. An isolated detachment does not “lose” because it lacks doctrine. It loses because it lacks batteries, parts, blood, sensors, antennas, filters, medicines, micro-drones, or electronic components that cannot be found locally.

Arc is based on this idea: if air access is blocked, if the roads are mined, if the port is closed, then the orbital trajectory becomes a bypass route. The argument is appealing because it bypasses the usual bottlenecks: diplomatic authorizations, weather windows, helicopter resupply within range of MANPADS, convoys under attack, etc.

But let’s be clear: “less than an hour” does not mean “instantaneous.” It means that the package is already in space, at the right time, and that a vehicle is in the right orbital position to trigger a re-entry compatible with the target area. Without this pre-positioning, the promise falls apart. Orbit is fast, but it is not magic.

The Arc principle and the reality of the announced figures

Arc is presented as a reusable orbital resupply capsule, of the “lifting body” type, i.e., a shape that generates lift during reentry to maneuver and target a landing zone, rather than falling like a simple ballistic heat shield.

The most widely cited public figures place Arc’s payload at around 225 kg (500 lb). This is small compared to a cargo plane, but huge for certain needs: batches of batteries, medical kits, drone components, critical parts, sensors, optics, radios, electronic warfare consumables, or specialized tools.

Another key point is the announced storage time: the idea is to leave loaded capsules in orbit for years, then trigger the descent “on command.” Here too, it is technically credible, but restrictive: some materials age poorly (batteries, medicines, polymers, adhesives, lubricants), and the space environment requires precautions (radiation, thermal cycles). For robust equipment, it is simpler. For sensitive biomedical equipment, it is another matter entirely.

Advanced precision is around 15 m (50 ft). On a map, that’s excellent. In the field, it’s not “I’m landing in your backyard.” It’s “I’m landing in a compatible area,” with safety margins and risk management if civilians are nearby.

Operational advantages and scenarios where Arc makes sense

The value of Arc is not to deliver “a lot.” It is to deliver “vital” when nothing else will.

The answer to isolated units and denied access

In areas where the adversary deploys ground-to-air defenses, jamming, and threats on the axes, a conventional logistics flow quickly becomes fragile. An orbital delivery, on the other hand, bypasses most local tactical threats… but not all: the recovery zone can be attacked, monitored, or booby-trapped.

Support for special forces and covert operations

For a team operating deep behind enemy lines, 225 kg can make all the difference: batteries, sensors, radio relays, small reconnaissance drones, repair kits, cutting charges, or critical consumables. In this case, Arc becomes a tool for “operational continuity,” not a space truck.

Logistical resilience in the face of setbacks

Modern logistics relies on hubs. Destroy one hub, and everything slows down. The idea of pre-positioned space logistics adds an option for continuity: not massive, but available when everything else is slow or impossible.

Real feasibility in the face of physical and tactical constraints

Saying “we can” is not enough. We need to look at what’s getting in the way.

The orbital constraint that dictates availability

To deliver in less than an hour, the orbit must “pass” close to the area, or a vehicle must have enough energy to adjust its trajectory. But maneuvers cost fuel. And fuel costs mass. And mass reduces payload. The slogan “anywhere on Earth within an hour” is therefore a vision of a constellation, not a guaranteed capability with a single vehicle.

Re-entry constraints and weather constraints

A controlled re-entry is a violent sequence: heating, plasma, structural loads, then the terminal phase. Ground weather conditions matter (wind, sea, visibility), especially if the objective is recovery by a small team. Delivery by sea may seem practical, but it requires naval recovery and carries a risk of loss.

Security and attribution constraints

A capsule arriving from the sky over a combat zone is a signature. Even if the trajectory is difficult to intercept, it is potentially detectable. And if it falls in the wrong place, it is a technological gift to the enemy. The tool must therefore incorporate anti-compromise measures (erasure, encryption, selective destruction), otherwise the military argument backfires.

The budget and economics of orbital delivery

The most “anti-marketing” point is also the most decisive: the price.

Inversion Space has announced that it has raised $44 million to push Arc towards orbital flight. This is consistent with developing a vehicle, but it is not the cost of a large-scale operational service.

The cost per mission will depend mainly on the launch. Putting 225 kg into orbit comes at a price. Even with low rideshare rates, the bill climbs as soon as you add the vehicle itself, operations, insurance, preparation, and recovery. On the other hand, a transport plane can deliver much more, but at the cost of safe air access, authorizations, and tactical risk.

Arc will therefore never be “cheaper” than conventional transport for volume. Its value must lie elsewhere: delivering when no one else can, and delivering items that are worth more than their transport (rare parts, critical batteries, vital medical kits, essential sensors). If Arc delivers 225 kg that prevent a mission failure or the loss of a position, then the calculation changes.

Links with military programs and the “Rocket Cargo” logic

Arc is entering an ecosystem where the Pentagon has been exploring rapid rocket transport for several years, notably via Rocket Cargo. There are two families that should not be confused:

- Delivery from orbit, Arc type: small payload, potentially pre-positioned, descent on demand.

- Suborbital point-to-point: very large payloads (up to tens of tons), but heavy infrastructure, landing sites, political risks, and a model closer to “strategic express cargo.”

Arc is positioned more as a complementary tactical precision tool. Point-to-point aims for strategic logistical impact.

The two concepts share a slogan (“in one hour”), but not the same industrial world or the same framework for use.

The concrete limitations and what will need to be proven in flight

A prototype that “looks plausible” is not enough. The milestones that matter are public and measurable.

Demonstration of a complete and recoverable reentry

A successful orbital flight, with controlled reentry, terminal guidance, and recovery of the vehicle in good condition, is the basis. Without actual reuse, the economics immediately deteriorate.

Demonstration of accuracy under realistic conditions

The announced accuracy must be validated with weather, winds, rough seas, and recovery scenarios. Landing “close” is one thing. Making the package usable quickly, without excessive exposure, is another.

Demonstration of an end-to-end logistics chain

The devil is in the integration: package preparation, long-term storage in orbit, triggering, communication, ground coordination, recovery, security, and return to service. Innovation is not only in re-entry. It is in the operational aspects.

Arc’s likely place in a real war

Arc seems like a simple idea, but it is based on a demanding logic: accepting to pay a high price to deliver a small amount, because that “small amount” changes the outcome of an action. It is a logic of high-intensity warfare and contested areas, not routine logistics.

If Arc delivers on its promises, it will not render aircraft obsolete. It will add an option: critical, fast delivery that is difficult to block, but costly and limited in mass. The real test will be the selection of payloads: those that are worth deorbiting. And if the announced constellation remains a distant prospect, its use could be concentrated on rare, highly targeted missions where the urgency and value outweigh the cost.

Sources

- Inversion Space — Arc product page

- Inversion Space — Newsroom (Ray, announcements)

- The War Zone (TWZ) — “Arc Orbital Supply Capsule…” (Nov. 6, 2025)

- Payload — “Inversion Space Unveils Arc Reentry Vehicle” (Oct. 2, 2025)

- TechCrunch — “Inversion Space gets reentry license…” (Oct. 15, 2024)

- U.S. Air Force — Rocket Cargo Vanguard (June 4, 2021)

- Space.com — article on Arc (Oct. 6, 2025)

- Gizmodo — summary of dimensions/payload (Oct. 4, 2025)

- AeroTime — “Inversion Space aims to deliver cargo…” (Oct. 9, 2025)

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.