In 2025, the US Air Force operates the oldest fleet in its history. Aging, maintenance costs, and reduced availability are weakening US air power.

Summary

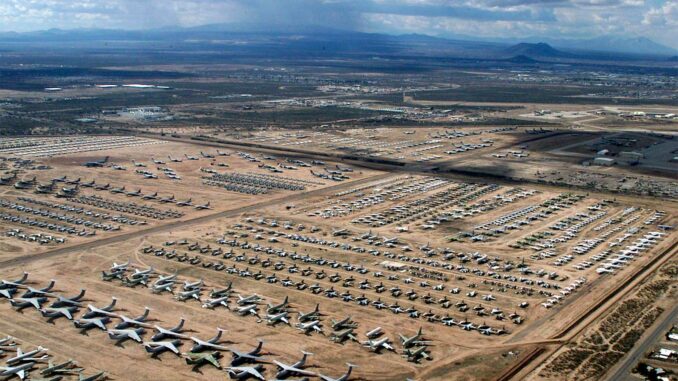

In 2025, the US Air Force faces a reality that is rarely acknowledged so clearly: its fleet is the oldest and smallest it has been in 78 years. The average age of its aircraft is now approaching 32 years, a critical threshold for an air force based on technological superiority and global projection capabilities. Strategic bombers, tankers, tactical fighters, and intelligence aircraft share the same problem: they were designed for a different strategic context and for much shorter lifespans. This situation fuels a maintenance spiral where budgets are absorbed by keeping aging aircraft airworthy, to the detriment of capacity renewal. The consequences are manifold: reduced availability, increased pressure on crews, weakened power projection, and increasingly constrained financial trade-offs. The US Air Force remains dominant, but this dominance now rests on a fleet that is aging faster than the solutions intended to replace it.

The reality of a historically aging fleet

Since its creation in 1947, the US Air Force has never reached such a level of aging. In the 1960s and 1970s, the average age of aircraft ranged from 10 to 15 years. Even after the end of the Cold War, it remained below 25 years. In 2025, the 32-year threshold marks a turning point.

This evolution can be explained by several converging factors. The reduction in size after the collapse of the Soviet bloc led to existing aircraft being kept in service for longer. Prolonged conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Middle East have led to accelerated wear and tear on airframes, far beyond initial assumptions. Finally, the dramatic increase in the unit cost of modern aircraft has limited the pace of acquisitions.

The fleet is therefore smaller, but above all more heavily used, which automatically accelerates its aging.

Strategic bombers, the old pillars of deterrence

The B-52, a symbol of extreme longevity

The B-52 Stratofortress epitomizes the current situation. Commissioned in the early 1950s, it has an operational life that will soon exceed 80 years. Its airframe was designed for approximately 20,000 flight hours, but some aircraft are now approaching or exceeding this threshold thanks to successive structural reinforcement programs.

However, its engines, structure, and some of its systems remain rooted in an outdated architecture. Each major maintenance operation requires rare skills and parts that are sometimes produced in very small quantities. The cost per flight hour is automatically increasing, even though the aircraft remains effective for certain missions.

The B-1B and the weight of structural fatigue

The B-1B Lancer, which entered service in the 1980s, suffers from another problem: intensive use at low altitude in the 1990s and 2000s accelerated the fatigue of its airframe. As a result, availability rates have sometimes fallen below 50%, forcing the US Air Force to ground several aircraft for lengthy and costly repairs.

Refueling aircraft, the Achilles heel of American projection

The United States’ global projection capability relies on in-flight refueling. However, this segment is one of the oldest in the fleet. The KC-135 Stratotanker entered service in the late 1950s. Its average age now exceeds 60 years.

Each inspection reveals new cracks, corrosion problems, or obsolete systems. The modernization of the avionics has extended its service life, but the structure remains a major constraint.

The KC-46 is supposed to take over, but its entry into service has been slowed by technical difficulties, particularly with the refueling and vision systems.

This situation creates a systemic vulnerability: an unavailable tanker immobilizes several fighters or bombers.

Tactical fighters under constant pressure

F-15s and F-16s beyond their initial horizon

The F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon still make up a significant part of the combat fleet. Many were delivered in the 1980s. They were designed for approximately 4,000 to 6,000 flight hours. Today, some exceed 8,000 hours.

Each extension requires thorough inspections and the replacement of stringers, frames, and structural panels. These operations are costly and immobilize the aircraft for long periods of time. This has a direct impact on operational availability.

An incomplete transition to new-generation aircraft

Replacement with newer aircraft is progressing, but at a pace that is insufficient to compensate for retirements. Older fleets therefore remain essential to maintain overall strength, even if they are no longer optimal when facing adversaries equipped with modern systems.

The maintenance spiral, a central mechanism of the crisis

The aging of the fleet leads to an exponential increase in maintenance costs. Parts are no longer mass-produced. Industrial lines must be restarted on an ad hoc basis. Downtime is increasing.

This maintenance spiral acts as a budgetary trap. The older the aircraft, the more resources they consume. These resources cannot then be invested in the development or purchase of new aircraft. The past cannibalizes the future.

For some fleets, support costs are increasing by several percentage points per year, regardless of general inflation.

Direct effects on operational availability

The most visible consequence is reduced availability. For several types of aircraft, operational rates struggle to exceed 60%. This means that nearly four out of ten aircraft are not immediately usable.

For units, this translates into more rigid planning, accelerated rotations of available aircraft, and increased pressure on crews. Room for maneuver is reduced, particularly in a high-intensity conflict scenario.

The impact on projection and deterrence capabilities

The projection of American power relies on a precise sequence: takeoff, transit, refueling, strike or patrol, return. Each link depends on the availability of the others. An aging fleet undermines this balance.

In a context of increased strategic competition, this situation raises a central question: the ability to sustain prolonged operations in multiple theaters simultaneously. The answer depends on logistical resilience and the ability to absorb failures, two areas directly affected by the age of the aircraft.

Budgetary constraints and trade-offs

The US Air Force has to work with large but not unlimited budgets. Every dollar spent on maintaining an old aircraft is a dollar that is not invested in a future program. Trade-offs are becoming increasingly difficult: extend, modernize, or retire.

Retiring too quickly reduces the overall fleet size. Extending too long increases costs and technical risks. Accelerating replacement programs involves massive investments and industrial risks.

Human and industrial consequences

The aging fleet also weighs on personnel. Mechanics must maintain systems that are sometimes outdated, with fragmentary documentation and rare parts. Training becomes longer and more specialized.

On the industrial front, maintaining old production lines ties up resources that could be devoted to emerging technologies. This inertia slows down the adaptation of air assets to new forms of conflict.

Air superiority under structural pressure

It would be wrong to predict an immediate decline of the US Air Force. It retains unparalleled power. But this power increasingly relies on aircraft designed for a world that no longer exists.

The central issue is therefore not current capacity, but medium- and long-term sustainability. If the pace of renewal does not accelerate, there is a risk of gradual erosion, which may be difficult to perceive in the short term but could have serious strategic consequences.

Sources

US Air Force Aircraft Inventory Reports

Congressional Budget Office – Military Aircraft Aging

US Department of Defense Sustainment Assessments

USAF Readiness and Availability Briefings

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.