Airbus Defence considers it “good” to have two fighter jets for the SCAF/FCAS. Analysis of the obstacles, costs, industrial roles, and risks of two medium-sized aircraft.

In summary

The head of Airbus Defense & Space, Michael Schöllhorn, is now embracing an option that has long been considered taboo: the SCAF/FCAS architecture could survive with two separate combat aircraft, rather than a single common fighter. The idea is simple. If Paris and Berlin cannot agree on the piloted “core,” it is better to decouple the problem, with each developing its own aircraft while retaining some of the common components. This recommendation comes after months of deadlock on governance, work sharing, and intellectual property, while the states are already financing a demonstration phase. On paper, two aircraft can “unblock” a stalled political program. In reality, the price to pay is high: duplication of testing, industrial lines, and development, leading to increased costs and the risk of delays. The European dilemma can be summed up as follows: preserve the unity of the program at the risk of getting bogged down, or accept a partial divorce at the risk of ending up with two less efficient solutions.

The context of a way out of the crisis that looks like an admission of failure

Airbus’s proposal did not come out of the blue. Since 2022, the three partner states have been financing a demonstration phase aimed at finalizing the architecture, maturing the technologies, and preparing the flight demonstrators. This stage is already governed by a public contract and an organization based on industrial “pillars.” But the most political pillar remains that of the piloted fighter, the NGF. This is where the tensions are the oldest and most paralyzing.

Europe has already experienced this scenario. When cooperation breaks down at the heart of a system, the program protects itself by saving what can be saved. This may seem like a technical solution, but it is primarily a governance solution.

Structural obstacles that have been undermining the program for years

The leadership dispute over the piloted aircraft

The sticking point is well known: who “designs” the fighter jet, who arbitrates, who decides when there is a conflict between military requirements and industrial constraints. Dassault Aviation defends a clear prime contractor approach to the aircraft, with the responsibilities and risks that go with it. Airbus, on the German and Spanish side, refuses to be reduced to the status of a subcontractor and is demanding a significant share of the design work.

The conflict is not a matter of ego. In a 20-year program, whoever controls the architecture controls exports, maintenance, upgrades, and part of the future modernization market.

The crux of intellectual property and transfers

The issue of technology transfers is the real fuel for the disagreement. Berlin wants to avoid a scenario where one company and one country capture the critical building blocks, while the others then “buy” their own sovereignty. Paris, for its part, wants to avoid the opposite scenario: having to share sensitive know-how to the point of losing its lead in architecture, stealth, or mission integration.

In short, European cooperation is facing a brutal reality: the more we talk about “European sovereignty,” the more national sovereignties reappear when it comes time to sign.

The timeline that makes each concession more costly

The demonstration phase is not an academic exercise. The partners have an operational objective around 2040 to replace the Rafale and Eurofighter. Every year lost today increases the cost of extending the current fleets, the MCO burden, and dependence on transitional solutions. Manufacturers know this. Military leaders know this. And yet, the political deadlock remains.

The figures that frame the debate and explain the nervousness

The contract for the current phase is often summarized as a Phase 1B budget of €3.2–3.85 billion, depending on the scope and public presentations, awarded “on behalf” of the three governments, with the DGA as the contracting authority.

This phase is expected to last approximately three and a half years and prepare the demonstrators.

Above that, public estimates of the complete program vary, but the most common reference in political and media discussions remains a total cost of €80-100 billion, sometimes more depending on whether industrialization, fleet acquisition, and associated systems are included. These amounts are not just “big numbers.” They dictate budgetary sustainability, and therefore the ability to maintain cooperation.

When Airbus mentions two aircraft, there is an immediate consequence: the cost of the piloted aircraft pillar increases, as economies of scale in development and industrialization are lost.

The program structure that makes the “two aircraft” conceivable

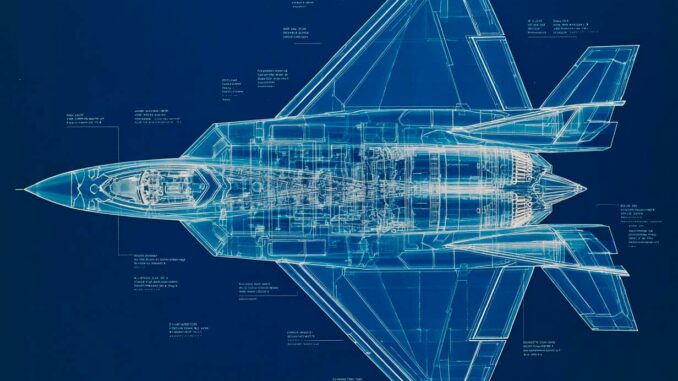

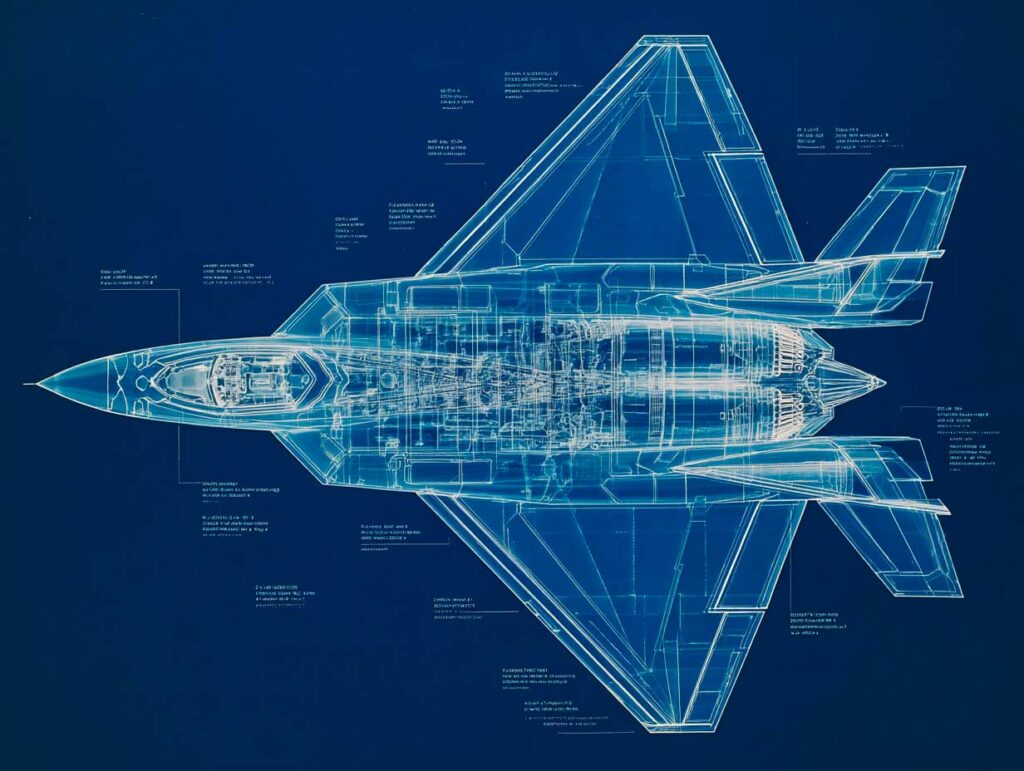

The SCAF is not just an aircraft. It is a “system of systems” built around technological and operational building blocks. The logic is to combine a piloted fighter, accompanying drones, and a combat data network.

The pillars officially described by public and industrial players provide a useful image: a piloted aircraft pillar, an engine pillar, a drone pillar, a cloud pillar, plus cross-cutting pillars (simulation, sensors, stealth). It is precisely because the program is modular that the “two fighter jets” option is not entirely absurd: common pillars could be retained and only the piloted aircraft separated.

But this is also where the pitfall lies: the more interfaces there are, the more difficult it becomes to maintain overall consistency when decision-making centers diverge.

The tactical reasons behind Airbus’ recommendation of this option

Separating the core conflict

The main objective is to break the industrial deadlock by isolating the point of friction. If cooperation on the fighter is impossible, Airbus wants to save the rest: drones, the cloud, certain sensors, simulation and integration environments.

This logic resembles a survival cure. It allows states to say, “the program continues.” Even if, in reality, the symbol of the “common European fighter jet” is fading.

The return to incompatible national needs

Behind the industrial dispute lie differences in requirements. France has a major constraint: a naval version compatible with a future aircraft carrier. This requirement imposes structural choices. It affects weight, structure, landing gear, resistance to landing, and often aerodynamic compromises.

Germany, on the other hand, does not have this constraint. It can focus on other priorities: range, payload, integration of national systems, collaborative combat doctrine, or NATO interoperability requirements. At some point, manufacturing a single aircraft that “does everything” can be more expensive and less satisfactory for everyone.

The implicit industrial argument

Airbus cannot afford, politically and industrially, to drop out of the game on the future European fighter. Offering two aircraft is also a way of preserving German national ambition and an industrial base, even if the initial cooperation fails.

The practical implications of a two-fighter SCAF

Duplication of the most expensive components

Developing two aircraft does not mean doubling “one design.” It often means doubling military certification, structural testing, flight test campaigns, weapons integration, industrialization, and tooling.

Unit costs also rise if each national fleet becomes smaller.

In practice, “two aircraft” could become “two programs,” with divergent schedules and multiplied risks.

The complexity of interoperability in a system of systems

Even if a common cloud, common drones, and a common doctrine are maintained, two different aircraft introduce differences in architecture, mission software, human-machine interfaces, and data standards. This is offset by layers of integration. But these layers are expensive, and they sometimes break the initial promise: simplicity and speed of decision-making in a network.

The risk of delaying the operational core

If France develops one aircraft and Germany another, it will be necessary to decide who flies when, who finances which demonstrations, and which system is “authoritative” for overall integration. Without an indisputable architectural authority, the whole thing can turn into a compromise factory.

The question of “who will do what” if we start with two aircraft

At this stage, there is no detailed, finalized public plan. But a coherent scenario is mechanically emerging.

On the French side, Dassault Aviation would take on the role of prime contractor for the national fighter, with its usual partners for integration, stealth, and systems. Naval constraints would reinforce this logic: France would not want a naval aircraft decided elsewhere.

On the German and Spanish side, Airbus Defence & Space would become the linchpin of a “continental” fighter, with a greater role for German and Spanish industry. Spain, via Indra, already has a structuring role in certain areas, particularly sensors, in the current organization.

The crucial question would then be: which components would remain common? Could the engine remain a shared effort around the existing joint venture? Would drones remain under Airbus leadership? Would the cloud remain tripartite with Thales and Indra? The more we keep in common, the more governance is needed. And it is precisely governance that has broken down.

Budgets and the question of “who will pay” in a two-aircraft scenario

Today, the logic is that the partner states jointly finance a demonstration phase, then move on to a development phase. Funding is provided through coordinated national budgets, with a contracting authority (on the French side) acting on behalf of the partners.

In a “two aircraft” scenario, two budgetary dynamics emerge.

The first, optimistic one is a distribution: each country finances “its” aircraft, while continuing to co-finance the common pillars. This reduces the battles over the workshare on the aircraft, but maintains the common bill for the rest.

The second, more realistic, is a scissor effect: each state agrees to finance more so as not to lose face, but economies of scale evaporate and the overall cost increases. At this level, the debate is no longer just industrial. It becomes parliamentary, and therefore fragile.

The controversial qualitative comparison: one better aircraft, or two lesser aircraft?

The honest answer is uncomfortable: it all depends on ambition and political realism.

Two aircraft can be “better” if each is optimized for its needs. A French naval aircraft, designed from the outset, may be more coherent than a single aircraft to which aircraft carrier requirements are added at a late stage. A German-Spanish aircraft, free from this constraint, may be lighter, simpler, and less expensive.

But the major risk lies elsewhere: if budgets do not increase in line with duplication, then each program will be forced to scale back its ambitions.

The result will be two “fairly good” aircraft, but neither will have the technological ambition of a single, concentrated effort. Europe will be left with two solutions, delays, and a bill that has grown.

This is where Airbus’s proposal should be seen as a political choice, not a technical optimization: we agree to pay more so as not to remain stuck.

The most likely outcome if nothing is clarified quickly

The political risk is now clear: save the “system” pillars (cloud, drones, sensors) and abandon the idea of a common fighter. German officials have already publicly suggested that a reduced FCAS could exist without a common aircraft, or with an aircraft developed separately. This is a way of avoiding the collapse of an emblematic program while acknowledging a reality: cooperation does not work when no one is willing to be number two.

The paradox is that this “downgraded” option can still produce useful building blocks. An interoperable combat cloud, collaborative drones, and data standards could benefit existing fleets before 2040. But this changes the initial promise: it is no longer “the European fighter of the future.” It is a patchwork of advanced modernization.

The final stretch that will decide whether Europe chooses efficiency or narrative

The “two aircraft” option is a last resort. It does not make the program more elegant. It simply makes it executable if trust is broken. The real debate is political: do governments still want a common symbol, or do they prefer to preserve their industrial bases, even if it means paying for duplication?

If Europe chooses two aircraft, it is not just choosing an architecture. It is admitting that industrial sovereignty remains national, and that “European” integration will be achieved through networks, drones, and data rather than through a single fighter jet. It is a coherent direction, but it is not the one that has been sold since 2017. And that is exactly why Airbus’s statement is more than just a comment: it is a sign of a break.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.