A crash involving an aircraft from the 432nd Wing near Area 51 led to a Temporary Flight Restriction and a joint investigation with the FBI. Technical analysis and issues at stake.

Summary

A US Air Force aircraft attached to the 432nd Wing at Creech AFB crashed on September 23, 2025, in the Nevada desert, about 20 kilometers from the edge of Area 51. The airspace was closed by Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR) up to an altitude of 4,572 m (15,000 ft). A curious fact: an “alteration” of the site after the debris was recovered was noted, prompting the USAF to refer the matter to the OSI and the FBI. The 432nd operates MQ-9 Reapers as well as stealth RQ-170 Sentinels via specialized squadrons. No confirmation of the exact type has been given. The coordinates of the TFR, close to the restricted areas of the Nevada Test and Training Range and the sector known as The Box, have fueled speculation. Beyond the sensationalism, the episode highlights three concrete issues: the security of sensitive tests, the protection of sensor/link technologies, and the robustness of procedures for guarding crash sites outside the base.

The established facts and their parameters: a crash under a “national security” TFR

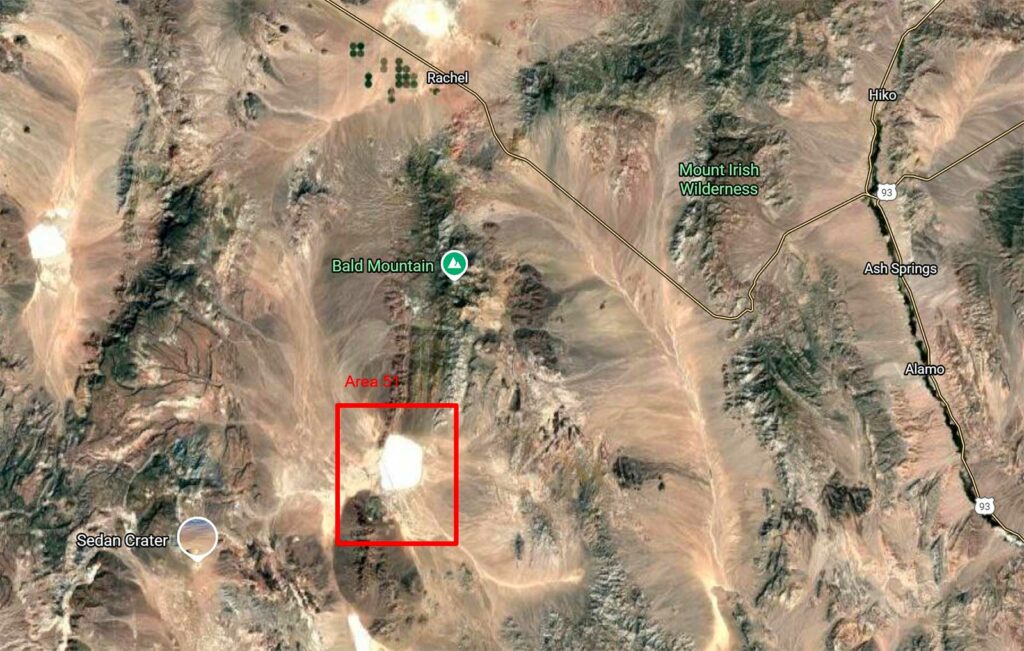

On September 23, 2025, an aircraft “assigned to the 432nd Wing” crashed without any casualties or damage to third parties. Air traffic is frozen for an hour: the Federal Aviation Administration issues a Temporary Flight Restriction with a radius of 5 NM (≈ 9.3 km) and a ceiling of 15,000 ft MSL (≈ 4,572 m), centered near Alamo, approximately 92 km north-northeast of Las Vegas and 91 km northeast of Creech AFB. The area is also located approximately 19 km east of the security perimeter of Area 51 and nearly 39 km from the Groom Lake facilities. The only public justification for the TFR is “national security.” The implementation of a TFR is standard after a military crash, but the “national security” motive combined with the proximity of the Nevada Test and Training Range has sparked the interest of spotters and the specialized media.

From a technical standpoint, a TFR at 15,000 ft is sufficient to cover the round trips of recovery helicopters, photo aircraft, and inspection drones. The 5 NM radius limits accidental overflights by general aviation and prevents unauthorized high-resolution image capture. The exemptions granted (Nellis ATC contacts) are explained by the density of activity above the NTTR. At this stage, the USAF only confirms that the aircraft belongs to the 432nd Wing, announces that there are no injuries, and then closes the recovery operation on September 27. The geometry of the TFR and the timeline (four days of active security, cleanup completed) reflect a rapid and controlled response: critical debris secured, possible decontamination, evacuation to a protected site for examination.

The unit and possible vectors: from the MQ-9 Reaper to the RQ-170 Sentinel

The 432nd Wing is the USAF’s first major combat drone unit. Based at Creech AFB, it fields MQ-9 Reapers (ISR/attack) and, within the 30th and 44th Reconnaissance Squadrons, the stealthy RQ-170 Sentinels. The MQ-9s are well known, numerous, and their incidents have been documented for years: their crash, in itself, does not justify an unusual level of secrecy, except in the case of sensitive configurations (undeclassified sensors, specific payloads). Conversely, a stealth drone such as the RQ-170 Sentinel carries low-signature technologies (airframe, air intakes, RAM processing), high-end sensors, and protected links. The post-crash preservation of these elements is strategic: any fragment of RAM skin, antenna, onboard processing, or recorder could be of interest to an adversary.

Does this mean we can conclude that it was an RQ-170? No: the USAF has not confirmed anything. However, we do know that RQ-170s regularly operate in and around the NTTR, including during exercises at Nellis. The proximity of The Box (sector R-4808A) and the NTTR sub-ranges increases the likelihood of discreet profile, sensor, or link testing. It should be noted that a crash “far” from Groom could also involve a transit vector, a sensor test flight, or “other” aircraft temporarily housed at Creech. The diversity of platforms (including transitory ones) and the porosity between units in the region (Nellis/Creech/Tonopah) make attribution difficult. One factual point remains: the aircraft is “assigned to the 432nd Wing.” This rules out foreign transit and reduces the likelihood of a non-USAF test aircraft.

The “pollution” of the site and the FBI: a signal of technological protection

On October 3, during a follow-up visit to the site, “traces of tampering” were discovered: the presence of an inert training bomb and an aircraft panel of “unknown origin” placed there after the incident. This simple detail justified a joint OSI/FBI investigation. Why? Because tampering with a military crash site can serve several purposes: 1) to conceal clandestine sampling; 2) to sow confusion about the nature of the aircraft; 3) to test security protocols for sensitive sites; 4) to influence the public narrative. The placement of an inert bomb casing can be interpreted as a message: to make people believe the aircraft was armed, to confuse the timelines, to occupy the investigation team with worthless artifacts.

Procedurally, the site was guarded until September 27. Once recovery was complete, the area was no longer under permanent “bubble” protection. In the open desert, the likelihood of local curiosity or intrusion by collectors is not zero. But the public announcement of an FBI investigation sends a signal: zero tolerance. For the USAF, the stakes go beyond this event. The aim is to prevent a chain of “curiosity → resale” from feeding private networks or, worse, opportunistic collections that could be exploited by foreign services. From a technical standpoint, even a small fragment of treated composite skin, a leading edge tile, a piece of embedded antenna, or a recording module can provide clues (dielectric constants, mesh, bonding processes, frequency signatures). The strong reaction protects these industrial secrets, if necessary through legal action.

The NTTR and The Box context: a very high-density ecosystem

The crash site is located on the edge of a puzzle of restricted areas managed from Nellis. The Nevada Test and Training Range aggregates sub-sectors (R-4807, R-4808, R-4809, etc.) where fighters, bombers, test aircraft, and drones train. At its heart, Area 51—The Box R-4808A—is the most restricted area, with specific coordination procedures and strict compartmentalization. This setting does not imply that an aircraft has violated “The Box” or left it. It means that any unusual activity within a radius of a few dozen kilometers is part of an environment where the Air Force tests, validates, and qualifies advanced technologies: sensors, links, signatures, C2 procedures.

For the USAF, the proximity of a crash to these areas increases the risk of “observation permitted by the accident.” Hence the use of a tight but sufficient Temporary Flight Restriction and minimal communication: confirmation of the connection (to cut short civilian rumors), zero precision of type (to avoid fueling speculation), announcement of the FBI investigation (to discourage unauthorized recovery). In terms of “test safety,” this type of incident typically triggers a review of test transport checklists, transit routes outside The Box, and post-recovery guard times. A predictable adjustment: extend the discreet surveillance window by 24–48 hours after lifting the TFR, and mark land access more precisely with mobile patrols and discreet optical means.

The capability implications: lessons for the fleet and the adversary

For the fleet, if the aircraft is an MQ-9 Reaper, the operational impact is limited: the support chain is well-established, accident documentation is abundant, and the fleet is large. If the aircraft is an RQ-170 Sentinel or an undisclosed stealth drone carrier, the impact is more significant: potential immobilization of a rare airframe, analysis of causes under secrecy constraints, and, above all, management of technical compromise risks. The unofficial rule is clear: a stealth aircraft lost outside a base requires meticulous tracking of fragments, down to the smallest debris. The cost is not insignificant, but it is less than the risk of replicating a surface process or exposing an antenna topology.

For the adversary, the episode confirms two realities. First, the United States makes intensive use of NTTR zones for training and testing, including with low-signature platforms; open observation of their “failures” is rare and valuable. Second, the responsiveness (immediate TFR, cleanup within 96 hours, FBI involvement) shows that technological protection is taken seriously even in the post-event phase. For state competitors, the learning curve is limited: no official photos of the wreckage, no confirmed clues as to the type. For curious locals, the red line has been drawn: a “prank” involving the placement of a dummy bomb at a sensitive site can result in police custody and prosecution.

In the medium term, it is in the USAF’s interest to standardize “crash site” kits for desert regions: anti-collection nets, captive camera drones, lightweight perimeter radars, and sheriff/county alert procedures. The cost is marginal compared to the value of a stealth “tile.” Finally, in terms of narrative, refusing to sensationalize is the right strategy: as long as we don’t know, we don’t know. The concrete figures (9.3 km radius, 4,572 m ceiling, 19/39 km distances) are sufficient to frame the event, without fantasies, and to remind us that a sparsely populated desert is not a free hunting ground.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.