Italy accuses London of blocking technology sharing on the 6th generation GCAP fighter jet, threatening industrial cooperation, defense budgets, and export competitiveness.

Summary

Italian Defense Minister Guido Crosetto accuses the United Kingdom of refusing to share key technologies within the tri-national GCAP program, conducted with Italy and Japan to deliver a 6th generation fighter by 2035. He describes this withholding of information as “madness” and “a great gift to the Russians and Chinese,” arguing that a program of this magnitude only makes sense if the partners have real access to the technological building blocks they are co-financing. At the same time, Italy’s design and development bill has risen from €6 billion to €18.6 billion in five years, making GCAP the most expensive military program in Rome’s recent history, ahead of the F-35. This tension over technology transfer comes at a time when the three main manufacturers—BAE Systems, Leonardo, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries—have created the Edgewing joint venture to carry out the aircraft’s design, and engine manufacturers Rolls-Royce, Avio Aero, and IHI have already begun joint work. Beyond the political dispute, the issue is strategic: overly restrictive sharing could weaken the cohesion of the alliance, increase costs, complicate sovereign maintenance, and reduce the export appeal of the future GCAP fighter compared to American competitors or potential European rivals.

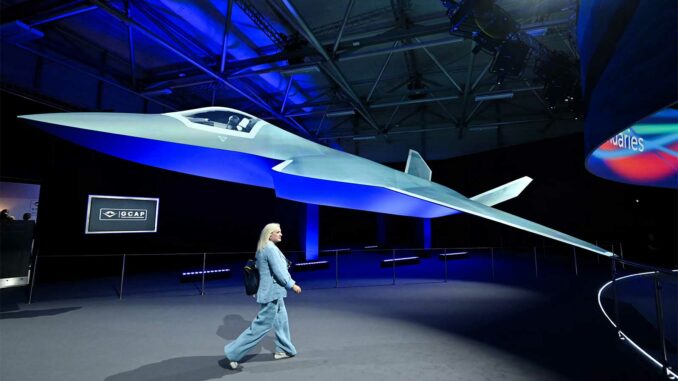

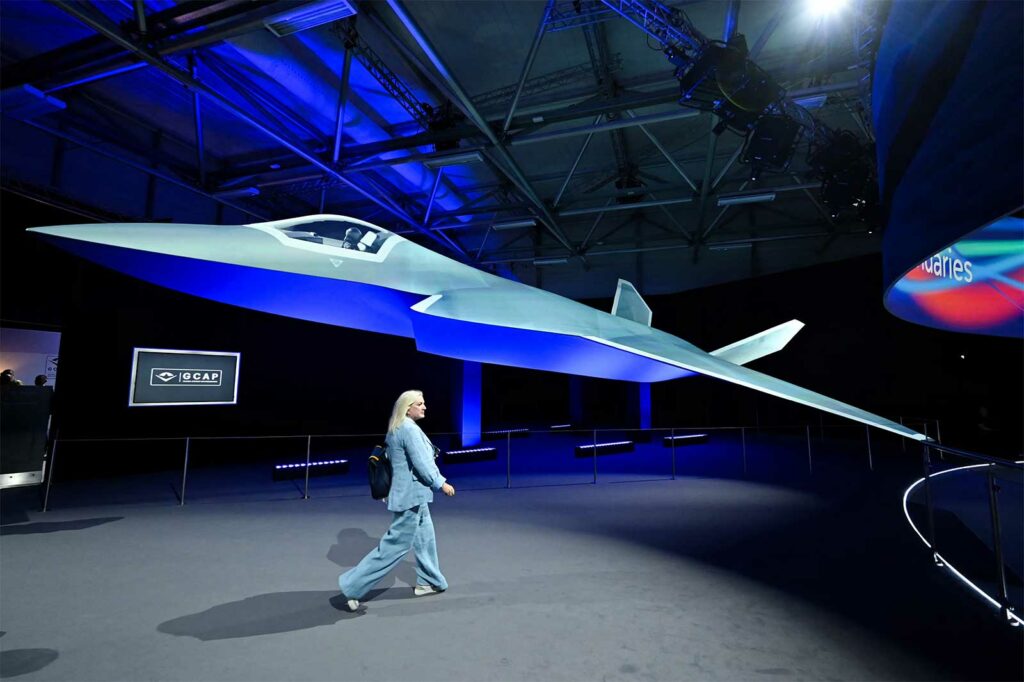

A reminder of the GCAP program and its ambitions

The Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) aims to develop a 6th generation fighter to replace the British and Italian Eurofighter Typhoons and the Japanese Mitsubishi F-2s from 2035 onwards. The project was officially launched in 2022, as an extension of the British Tempest concept, but structured from the outset as an “equal” partnership between London, Rome, and Tokyo.

On the industrial side, the program’s architecture is based on three national pillars: BAE Systems for the United Kingdom, Leonardo for Italy, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for Japan. In 2024, these three players formed the Edgewing joint venture, responsible for the complete design, production, and support of the future aircraft throughout its life cycle. At the same time, an engine consortium bringing together Rolls-Royce, Avio Aero, and IHI was formed to develop a new-generation engine, with work already underway on advanced combustion chambers.

The stated political objective is twofold: to ensure the long-term air sovereignty of the three partner countries and to create a platform that is sufficiently modular to conquer export markets in a “globally competitive environment.” With this in mind, governments are insisting that “exportability” is at the heart of the program, with potential customers increasingly asking to be partners rather than mere buyers.

Crosetto’s attack on “British secrecy”

Guido Crosetto’s statements are part of a standoff that has been going on since at least 2025. In April of that year, the Italian minister denounced the UK’s “barriers of selfishness” and accused it of not fully sharing certain technologies with Italy and Japan. He emphasized that, in his view, Italy had “completely” removed these barriers, Japan had “almost completely” removed them, while London remained reluctant to share expertise deemed sensitive.

In January 2026, when questioned in Rome, Crosetto insisted that nothing had changed, stating that the British “did not want” to share and describing this attitude as “madness” at a time when cohesion between allies was strategic. He went further, saying that such behavior was a “huge gift to the Russians and the Chinese,” suggesting that the lack of technological integration between Western partners was weakening the entire defense ecosystem.

In an attempt to gain the moral high ground, the minister said he had instructed Leonardo to share its own technologies within the GCAP, implicitly inviting London and Tokyo to do the same. For its part, the British Ministry of Defense defends the program as an “excellent example” of cutting-edge international cooperation, while remaining discreet about the precise nature of the technologies involved in the tensions.

The heart of the problem: technology transfer between allies

At the heart of this confrontation lies the perennial issue of technology transfer in multinational weapons programs. In concrete terms, this covers access to combat system source codes, data fusion algorithms, sensor architectures, “aircraft system” software layers, and the industrial processes required for heavy maintenance.

For non-lead partners—in this case Italy and, to a certain extent, Japan—the challenge is to avoid becoming entirely dependent on London for modernizing, repairing, or adapting their fleets, particularly in the event of a crisis or political differences. Without sufficient access to critical components, a country may pay its share of the program while remaining captive to the industry and administration of the lead nation.

For the United Kingdom, which developed the Tempest concept and has major assets in the fields of radar, electronic warfare, mission software, and engines, there is a strong temptation to protect certain “crown jewels.” Sharing technologies considered strategic involves risks in terms of export controls, proliferation, or potential leaks to other powers, especially if new partners such as Saudi Arabia join the venture.

This tension between technological sovereignty, proliferation control, and the requirement for reciprocity is at the heart of the dispute. Crosetto makes it a matter of principle: in his view, a country cannot be asked to finance a program worth tens of billions of euros without being given full access to the technical details of the aircraft it will receive.

Italian budgetary pressure and internal debate

Italian criticism can also be explained by budgetary dynamics. Between 2021 and 2026, Rome’s projected expenditure for the design and development of the GCAP has more than tripled, from €6 billion to €18.6 billion. This increase makes the GCAP the most expensive program in the recent history of the Italian armed forces, ahead of the €18 billion spent on the acquisition of 90 F-35s.

This estimated cost overrun is fueling political controversy, particularly from the Five Star Movement, which denounces the project as “prohibitive” in a country facing other social and economic priorities. In this context, Crosetto’s argument – “if we pay, we must receive the technology” – also becomes a tool for justification in the eyes of Italian public opinion.

The minister is playing the transparency and industrial return card: Italy is betting that investments in GCAP will support skilled employment and national expertise in electronics, aerodynamics, and mission systems, and will open up export markets for Leonardo and its subcontractors. Without technology transfers commensurate with the financial effort, the political equation becomes difficult to defend in Rome.

The impact on industrial architecture and value chains

The dispute over technology sharing could have profound consequences for the industrial architecture of GCAP. The partners have so far shown a willingness to break away from the more rigid model of the FCAS program, which has been undermined by disputes over task sharing between Dassault and Airbus. GCAP, on the other hand, was intended to be a laboratory for integrated cooperation, with mixed teams and a balanced sharing of responsibilities.

In reality, each country is keen to preserve critical capabilities on its own territory, particularly final assembly lines and heavy maintenance centers, which guarantee operational autonomy and a visible industrial return. It is already envisaged that each nation will have its own assembly line, similar to the Cameri site for the F-35 in Italy, which has become a major maintenance hub for other European users.

However, if London locks down certain components—such as electronic warfare or data fusion modules—the Italian and Japanese sites could find themselves confined to “surface” assembly, without complete control over the critical layers. This would weaken the local value chain, limit technological spin-offs, and complicate the creation of regional champions capable of exporting derivative subsystems.

Conversely, more generous sharing would allow Leonardo, Avio Aero, or Japanese manufacturers to develop variants, upgrades, and derivative products, strengthening the GCAP ecosystem and the collective capacity to evolve the aircraft over several decades.

The consequences for the global fighter market

The future GCAP fighter will enter an extremely competitive market currently dominated by the American F-35 and, in the long term, by other 6th generation projects such as the American NGAD or a possible European solution resulting from the FCAS. In this context, technology transfer and the ability to offer a genuine industrial partnership have become decisive commercial arguments.

Feedback from the F-35 program shows that “tier 2” partners—such as Italy and the Netherlands—have obtained significant industrial benefits and partial access to technologies, but remain dependent on American decisions for major developments. GCAP, on the other hand, aims to offer a formula whereby non-US countries can shape the aircraft, its sensors, and its combat cloud, with greater leeway on exports.

If the current disputes are not resolved, the program’s image could be damaged among potential customers, particularly in the Middle East and Asia, who are looking for both a high-performance system and a local development or assembly partnership. Saudi Arabia, which has expressed interest in joining GCAP from 2023, is closely watching how London manages the balance between protecting its technological base and opening up to partners.

The risk is that British rigidity on secrecy will push some states to favor either the F-35, despite its constraints, or alternative solutions—including outside the Western camp—that accept more transfers, particularly in the field of combat drones or command systems.

The effect on the schedule, costs, and strategic credibility

For the time being, the authorities insist that the GCAP program remains on track for entry into service around 2035, even though Japan has raised questions about the ability to meet this schedule. Any delays would not be solely related to disputes over technology transfer, but the latter could complicate the ramp-up of joint teams and system architecture decisions.

Friction could result in duplication of effort, with each country seeking to develop its own modules to avoid being held hostage by the other, which would increase costs and complicate integration. Ultimately, this could undermine the initial promise of GCAP: to pool investments in order to contain the overall cost of an extremely complex and connected combat system.

Strategically, the controversy also provides ammunition to those in Europe who advocate for more strictly national or bilateral programs, believing that large projects involving three or four countries are doomed to political deadlock. The contrast with the difficulties of the FCAS – where the issue of workload sharing between Dassault and Airbus threatens the very future of the program – is a constant feature of analyses of Europe’s position in defense.

If GCAP were to falter in turn, Europe would see two of its sixth-generation platforms weakened, at a time when the United States and other players are advancing their own solutions, with vastly superior research and development budgets.

Cooperation put to the test rather than buried

There is no indication at this stage that the tensions surrounding “British secrecy” are likely to immediately derail GCAP, but they do reveal deep divisions. Recent meetings between Giorgia Meloni and Japanese Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae have welcomed the progress of the program, a sign that Tokyo is seeking to bide its time and stay the course.

What happens next will depend on the ability of the three capitals to devise governance and technology protection mechanisms that reassure London without marginalizing Rome and Tokyo. This will likely involve defining differentiated confidentiality circles, conditional access rights, and guarantees on industrial benefits, rather than pitting total openness against absolute secrecy.

The debate launched by Crosetto, abrupt but deliberate, challenges Europe and its Asian allies to prove that they can build a sixth-generation fighter jet without repeating the deadlocks and rivalries of the past. If GCAP manages to turn this crisis into clarification, the program could emerge stronger, with a clearer balance between national sovereignty, risk sharing, and technological cooperation.

Sources

Defense News, “Madness: Italy’s Crosetto slams British secrecy on GCAP fighter jet,” January 30, 2026.

EurAsian Times, “British 6th-Gen GCAP Fighter Jet Faces Italian Fury!,” January 31, 2026.

Zona Militar, “Italy accuses the United Kingdom of not sharing key technologies for GCAP,” April 20, 2025.

FW‑MAG, “GCAP: some industrial details emerge for production and work sharing,” January 8, 2025.

Defcros News, “Italy’s Crosetto Criticizes British Secrecy Regarding GCAP,” January 29, 2026.

FlightGlobal, “How partners will stay in formation as GCAP workshare discussions advance.”

South China Morning Post, “‘Selfish’ UK rebuked for not fully sharing fighter jet project tech with Italy, Japan,” April 15, 2025.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.