Discover and undestand the Ogaden War (1977–1978) between Ethiopia and Somalia: causes, key players, battles, and consequences.

The Ogaden War (1977–1978): Military conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia over territorial control

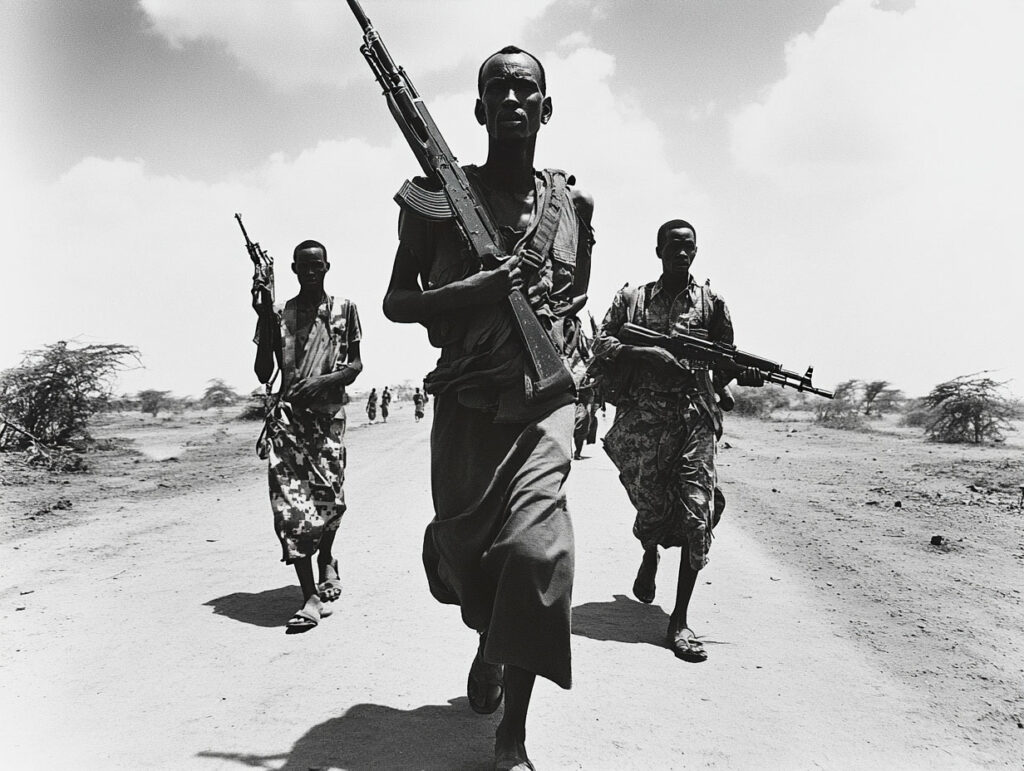

The Ogaden War (1977–1978) was a military conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia over the Ogaden region, a territory in eastern Ethiopia populated primarily by ethnic Somalis. Somalia, under President Siad Barre, aimed to annex the Ogaden region and integrate it into a Greater Somalia. Ethiopia, led by the Derg military regime, resisted the incursion. The war began in July 1977 when Somali forces launched a full-scale offensive. Initially, Somalia gained ground, but a shift occurred in early 1978 when Ethiopia, heavily backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba, launched a counteroffensive. The Somali troops were eventually pushed out by March 1978. The conflict caused heavy casualties, displacement, and long-term political and military consequences in the Horn of Africa.

What were the reasons for the Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The Ogaden War stemmed from territorial, ethnic, and ideological tensions in the Horn of Africa. At the heart of the conflict was the Ogaden region, a territory of about 200,000 square kilometers within Ethiopia, home to a majority ethnic Somali population. Somalia viewed this territory as part of a pan-Somali nationalist project aimed at uniting all ethnic Somalis under one national flag.

Somalia’s objective was the realization of Greater Somalia, a vision supported by earlier Somali governments and codified in Article 1 of the 1960 Somali Constitution. The Ogaden region, along with parts of Kenya and Djibouti, was included in this expansionist aim. This nationalist ideology had existed since independence in 1960 and was further amplified under the rule of Siad Barre, who believed that Ethiopia’s internal instability could allow a swift territorial gain.

Ethiopia, meanwhile, had entered a period of internal crisis after the 1974 overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie by the Derg, a Marxist-Leninist military junta. The country was affected by civil war, peasant revolts, and ethnic insurgencies, particularly in Eritrea and Tigray. This internal fragmentation made the country appear militarily weak.

From a geopolitical standpoint, both Ethiopia and Somalia were competing for influence during the Cold War. Initially, both countries had close ties with the Soviet Union. Somalia was receiving Soviet military aid since the early 1970s, and Ethiopia followed suit after 1974. However, the Soviet Union switched sides during the war, abandoning Somalia in favor of Ethiopia, which promised stronger adherence to a Marxist-Leninist model.

The final catalyst for the conflict was cross-border infiltration by the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), a Somali-backed guerrilla movement operating inside Ogaden. The WSLF had been active since early 1970s, escalating tensions. In July 1977, Somalia launched a full military invasion, converting the proxy conflict into a full-scale war.

Who was involved in the Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The Ogaden War involved two primary state actors, Somalia and Ethiopia, but was significantly influenced by external state and non-state actors, making it a complex regional conflict with global Cold War implications.

Somalia committed nearly 35,000 regular troops, supported by approximately 15,000 WSLF insurgents. The Somali National Army (SNA) was equipped with T-54 and T-55 tanks, BM-21 Grad rocket launchers, BTR-60 armored personnel carriers, and MiG-21 and MiG-17 fighter aircraft. These were primarily supplied by the Soviet Union before the war.

Ethiopia, despite initial weaknesses, mobilized approximately 100,000 troops by late 1977. The Ethiopian Army had suffered organizational decay after the revolution, but retained large numbers of Soviet-supplied tanks, artillery, and aircraft, including MiG-21s and SU-7 bombers.

During the course of the war, the Soviet Union shifted its support to Ethiopia, delivering $1 billion in military aid, including heavy armor and air support. This was accompanied by the deployment of up to 17,000 Cuban combat troops and around 1,500 Soviet military advisors. Cuba contributed elite infantry, artillery units, and air support, tipping the balance of power.

The United States, which had previously supported Ethiopia during the Haile Selassie era, remained largely passive during the early stages of the war. However, it began re-engaging with Somalia diplomatically and militarily after the Soviets defected to Ethiopia.

The conflict also involved East German and South Yemeni advisors on the Ethiopian side and minor involvement from Libya and North Korea on the Somali side. The Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), although a non-state actor, was a critical tool of Somali policy in the region.

The geopolitical alignment shift during the war, with the Soviet-Cuban axis supporting Ethiopia and Somalia leaning towards Western powers, turned a regional conflict into a Cold War battleground.

The leaders of the Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The Ogaden War was shaped by the political and military decisions of key figures in both Ethiopia and Somalia.

Siad Barre, President of Somalia from 1969 to 1991, was the principal decision-maker behind the invasion of Ogaden. A former army commander, Barre had seized power in a 1969 military coup and imposed a scientific socialism model inspired by Marxism-Leninism. His pursuit of Greater Somalia was a central part of his regime’s ideology. He believed the weakening of Ethiopia post-1974 provided a strategic window to annex Ogaden. Barre authorized full mobilization of the Somali army and coordinated operations alongside the Western Somali Liberation Front.

Mengistu Haile Mariam, a military officer and de facto head of state of Ethiopia after 1977, emerged as the primary Ethiopian figure. Mengistu had assumed control after purging rival officers during the Red Terror campaign. He strengthened the Derg’s ideological alignment with the Soviet Union and coordinated the integration of foreign assistance, particularly Cuban and Soviet forces, into the Ethiopian military structure.

Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba, played a decisive role by sending combat troops and advisors to Ethiopia. Castro saw Ethiopia as a strategic ally in Africa and justified intervention under the banner of defending revolutionary socialism.

Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, facilitated the realignment of Soviet foreign policy towards Ethiopia. The Kremlin prioritized Ethiopia’s strategic location on the Red Sea and sought to expand influence through ideological partnership.

General Samora Machel of Mozambique and South Yemeni leader Abdul Fattah Ismail were indirectly involved by supporting Ethiopia’s Marxist bloc. Conversely, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi of Libya and North Korean leader Kim Il Sung expressed rhetorical and material support for Somalia.

Leadership decisions—both domestic and international—were central in prolonging and escalating the war. The military coordination between Mengistu, Soviet advisors, and Cuban commanders proved more sustainable than the initially superior Somali strategy.

Was there a decisive moment? (350 words)

A critical shift in the Ogaden War occurred between December 1977 and February 1978, when Ethiopian forces—now supported by Cuban troops and Soviet advisors—launched a large-scale counteroffensive that reversed earlier Somali gains.

Initially, Somalia had captured approximately 90% of the Ogaden region. Towns like Jijiga, Gode, Kebri Dahar, and Degehabur had fallen to Somali and WSLF forces. However, Somalia lacked sufficient logistical capacity to maintain deep advances and defend long supply lines across rough terrain. The Ethiopian command exploited this vulnerability with coordinated air-ground operations using Soviet-supplied equipment and Cuban infantry.

One of the decisive military operations occurred in January 1978, during the Battle of Jijiga, where Somali forces were pushed out by a combination of Ethiopian artillery barrages, Cuban tank units, and close air support. The involvement of 13,000 Cuban combat troops in multiple sectors provided Ethiopia with experienced ground fighters and technical superiority.

The introduction of advanced Soviet logistics, including Mi-24 helicopter gunships, mobile SAM units, and radar-guided artillery, allowed Ethiopia to target Somali supply convoys and rear positions with greater precision. These technological advantages were decisive in cutting off Somali units from resupply and reinforcements.

A political component also shaped the decisive moment. After recognizing the shift in Soviet support and facing growing internal dissent, Siad Barre withdrew Somali forces in March 1978. He declared the war unwinnable without Soviet backing and sought diplomatic solutions through the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), though without success.

The Ethiopian recapture of major towns and the collapse of the Somali offensive front marked the decisive phase. From this point, Somalia no longer had the strategic capacity to retake Ogaden. Ethiopia reestablished control over most of the contested territory, solidifying the reversal.

This period marks the clear transition from Somali initiative to Ethiopian dominance, driven primarily by foreign intervention and a shift in battlefield control. It did not end the Somali national objective, but it ended the conventional military phase of the Ogaden War.

Major battles of the Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The Ogaden War involved a series of high-intensity battles, many of which took place in strategic towns and logistical choke points in eastern Ethiopia. Below are the most significant engagements.

Battle of Gode (July–August 1977)

Gode, a key crossing on the Shabelle River, was one of the first targets of the Somali offensive. The Somali 60th Division, supported by WSLF units, overran Ethiopian positions by August 1977, capturing Gode after intense artillery exchanges. This gave Somalia access to supply routes in the interior and a bridgehead to launch further advances.

Battle of Jijiga (September 1977 – January 1978)

One of the largest confrontations occurred in Jijiga, the regional capital of the Ogaden. Somalia initially seized the town in September 1977, following coordinated infantry and armored attacks. The Ethiopian 3rd Division suffered major losses and withdrew. However, the Ethiopian-Cuban counteroffensive in January 1978 was decisive. Cuban Mi-8 helicopters, T-62 tanks, and elite infantry units led the assault. Ethiopia retook Jijiga after a multi-day battle, marking a turning point in the war.

Battle of Dire Dawa (August 1977)

Somalia attempted to capture Dire Dawa, a critical rail and air transport hub. A combined Somali-WSLF assault was launched with tanks, mortars, and air support. Ethiopian forces defended the city using MiG-21s and ground-based artillery. The assault failed, making Dire Dawa one of the few major Ethiopian cities to resist occupation. The failure prevented Somalia from disrupting Addis Ababa’s supply corridor.

Battle of Harar (December 1977 – February 1978)

Harar was another strategic target, controlling the route between central Ethiopia and the Ogaden. Somali forces encircled the city and launched continuous assaults, but were unable to break Ethiopian defenses. Cuban artillery and air support played a decisive role. The Ethiopian-Cuban counteroffensive in February 1978 repelled Somali units and stabilized the front.

Counteroffensive in the Ogaden (January–March 1978)

From January 1978, Ethiopia launched a full counteroffensive across multiple fronts. Reinforced with Cuban brigades, the Ethiopian Army retook Gode, Kebri Dahar, Degehabur, and Warder. The campaign featured combined arms operations—air strikes, armored pushes, and infantry envelopments. Somali resistance collapsed under pressure, and by March 1978, nearly all captured territories were retaken.

These battles illustrate the shift from Somali offensive dominance to Ethiopian-Cuban counteroffensive supremacy, underlining the importance of logistics, foreign support, and sustained ground coordination.

Was there a turning point?

The turning point of the Ogaden War occurred between December 1977 and February 1978, when the Ethiopian government, bolstered by Soviet logistics and Cuban combat support, managed to regain operational control and shift the momentum of the war.

Until late 1977, Somali forces had gained control over most of the Ogaden region, occupying key towns such as Jijiga, Gode, and Degehabur. Ethiopia’s army was still recovering from internal purges and reorganization following the 1974 revolution, which had weakened command structures and unit cohesion. However, the injection of Soviet-supplied weapons systems, including T-62 tanks, SA-6 surface-to-air missile systems, and Mi-24 helicopters, began to change the battlefield dynamics.

Cuba’s military involvement, consisting of more than 13,000 soldiers, provided the Ethiopian army with experienced infantry and logistical expertise. These forces were deployed strategically to frontlines near Harar and Jijiga, allowing for the reorganization of the Ethiopian military structure into a more effective fighting force.

One of the key factors that marked the turning point was the retaking of Jijiga in January 1978. The Ethiopian-Cuban operation involved coordinated armor assaults, air cover, and artillery bombardments, forcing Somali units to retreat. This success disrupted Somalia’s eastern defense lines and forced a general withdrawal.

At the same time, Somalia began experiencing domestic pressures. The war was becoming unpopular within Somalia due to high casualty numbers, logistical strains, and the abandonment by the Soviet Union, which had been Somalia’s main weapons supplier. With no comparable Western support to replace Soviet aid, the Somali offensive lost sustainability.

Another critical aspect was the Ethiopian military’s reassertion of aerial superiority. Using Soviet aircraft and radar-guided systems, they were able to neutralize Somali air strikes and target supply routes in the rear, creating tactical isolation for Somali forward units.

By March 1978, most Somali forces had withdrawn or been expelled from Ogaden. The period between late 1977 and early 1978 was thus the turning point, driven by external military aid, improved Ethiopian coordination, and the Somali regime’s strategic overstretch.

Consequences of the Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The Ogaden War left deep military, political, and geopolitical consequences across the Horn of Africa and beyond.

For Somalia, the war was a major strategic failure. Despite initial territorial gains, the loss of Soviet support, combined with the failure to secure Western military aid of equivalent scale, severely weakened its army. Tens of thousands of Somali troops were lost, and the war consumed vast resources. The defeat undermined Siad Barre’s internal legitimacy, leading to growing opposition movements such as the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) and eventually contributing to the Somali Civil War (1991–present).

Domestically, Somalia experienced political fragmentation. Clan-based factions gained influence, and by the mid-1980s, Somalia had entered a prolonged period of instability. The defeat also ended any viable military option to pursue the Greater Somalia project.

For Ethiopia, the war was a military recovery milestone. It allowed the Derg regime under Mengistu Haile Mariam to consolidate power, enhance Soviet relations, and reassert national sovereignty. The Soviet-Cuban alliance expanded influence in Ethiopia, making it a regional proxy for Soviet interests during the Cold War. However, Ethiopia’s internal issues persisted. While the Ogaden War was a short-term success, it diverted attention and resources from insurgencies in Eritrea, Tigray, and Oromo regions, which would later escalate.

The war also had significant human costs. Estimates suggest up to 30,000 soldiers killed, with tens of thousands more wounded. Civilian displacement was widespread—hundreds of thousands of Ogaden residents became refugees, fleeing to Somalia, Djibouti, and Kenya. Infrastructure in Ogaden was damaged or destroyed, and access to food and medical care deteriorated.

Geopolitically, the war realigned regional alliances. The Soviet Union shifted focus from Somalia to Ethiopia, causing Somalia to move closer to the United States, receiving limited arms support from 1979 onward. The Cold War rivalry in Africa intensified, with both superpowers competing through proxy regimes.

The Western Somali Liberation Front, which had initially supported Somalia’s goals, remained active but increasingly marginalized. The conflict created long-term distrust between Somali and Ethiopian states, affecting border security and regional diplomacy for decades.

In sum, the Ogaden War reshaped the political landscape of East Africa, contributing to state fragmentation, enduring military instability, and a shift in superpower influence in the region.

Back to the Wars section