A full technical analysis of the US Invasion of Panama in 1989: motivations, actors, operations, consequences, and tactical outcomes.

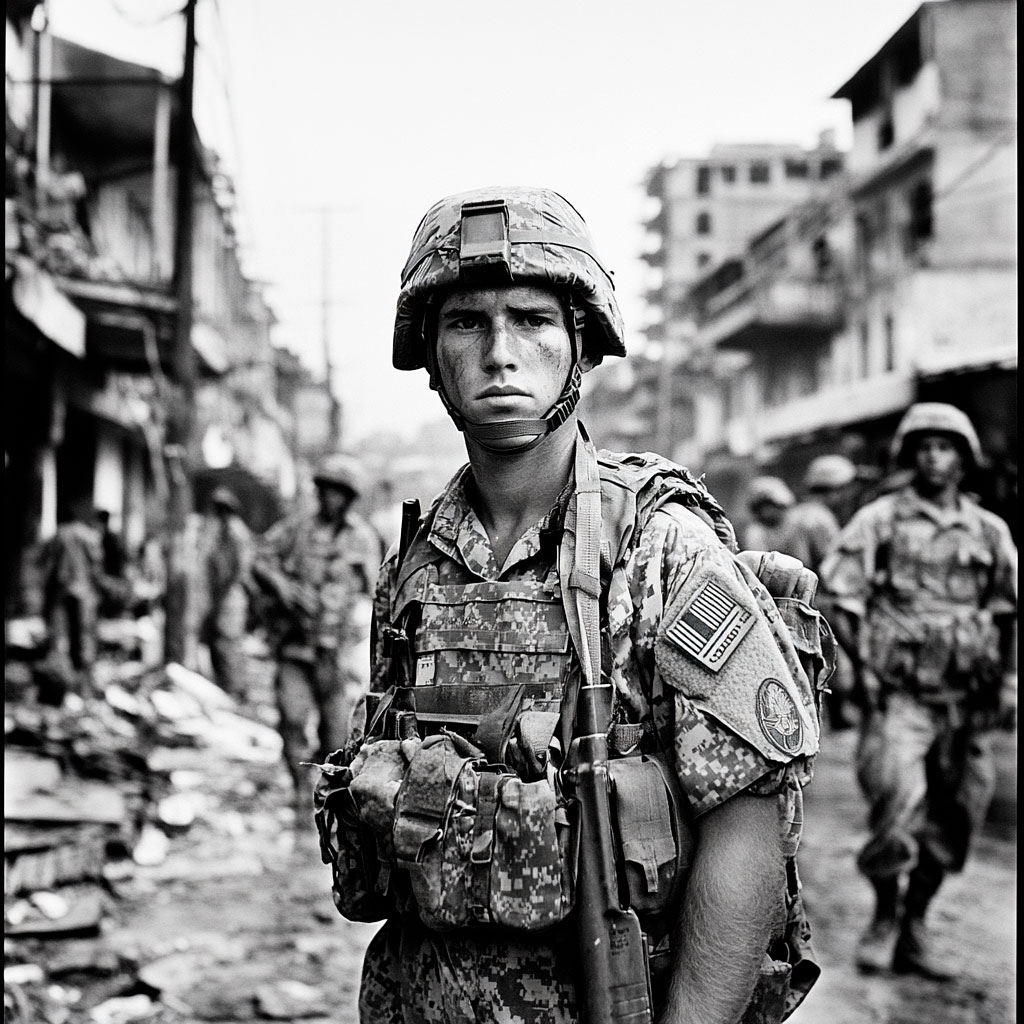

The US Invasion of Panama, known as Operation Just Cause, began on 20 December 1989. It aimed to remove General Manuel Noriega from power and secure US strategic interests in the Panama Canal Zone. The operation involved more than 27,000 US troops and over 300 aircraft, facing around 16,000 Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF). The invasion was executed with overwhelming military superiority. Within days, Noriega had taken refuge in the Vatican Embassy, and by 3 January 1990, he surrendered to US forces. The invasion caused hundreds of deaths, significant infrastructure damage, and widespread political consequences. It ended Noriega’s rule and led to a new Panamanian government aligned with US policy. The operation also prompted legal and political debates over US military interventions and set a model for rapid deployment warfare that influenced subsequent conflicts.

What Were the Reasons for the US Invasion of Panama (1989)

The US invasion of Panama was triggered by a combination of strategic, political, and operational concerns. The official justification emphasized the protection of US nationals, defense of democracy, combating drug trafficking, and securing the Panama Canal Zone.

The Panama Canal Treaty, signed in 1977, planned for the full transfer of the canal to Panama by 31 December 1999. US officials feared instability under Noriega could compromise the canal’s neutrality and security. Approximately 35,000 US citizens lived in Panama, many in the Canal Zone, and rising tensions raised concerns for their safety.

Another reason was the escalation of Noriega’s anti-American rhetoric and his control of the Panamanian Defense Forces. He had annulled democratic elections in May 1989, where opposition candidate Guillermo Endara had won. This move triggered domestic unrest and international condemnation.

Noriega was also under indictment in the United States on charges of drug trafficking and money laundering since February 1988. He had maintained close ties with the Medellín cartel, facilitating cocaine shipments through Panama. Although he had cooperated with US intelligence in the past, his relationship with Washington had deteriorated severely by 1989.

In December 1989, Noriega’s forces shot and killed a US Marine, Lt. Robert Paz, in Panama City and temporarily detained other American personnel. This incident, described as an attack on US service members, accelerated Washington’s decision to intervene militarily.

President George H. W. Bush authorized the invasion on 20 December 1989. The operation aimed to remove Noriega, disband the Panamanian Defense Forces, and install the legitimate government led by Endara. These objectives were tied directly to broader US policy in Latin America, particularly the war on drugs and maintaining influence in the region.

Who Was Involved in the US Invasion of Panama (1989)

The conflict involved US military forces, the Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF), and the newly elected civilian leadership of Panama.

On the US side, more than 27,000 troops were deployed, supported by 300 aircraft from multiple branches: Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps. This included Rangers, 82nd Airborne Division, SEAL Teams, and Delta Force units. Operation Just Cause was a joint combat operation, requiring coordination between Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM).

Major US units included:

- 82nd Airborne Division (paratroopers)

- 7th Infantry Division (Light)

- 75th Ranger Regiment

- US Navy SEALs

- Delta Force (1st SFOD-D)

- 160th SOAR (Night Stalkers)

Support units included:

- Military Police

- Psychological Operations units

- Civil Affairs teams

The Panamanian side consisted of the Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF), a military and paramilitary force of around 16,000 personnel, including:

- Infantry battalions

- Special forces

- Police units

- Dignity Battalions (irregular civilian militias loyal to Noriega)

The PDF was poorly equipped and fragmented. Its command structure was under Noriega’s tight control, with key units based in Panama City, Fort Amador, and Rio Hato.

In the political sphere, Guillermo Endara, elected president in May 1989, had been forced into hiding after Noriega nullified the election. The US installed Endara as president shortly after the invasion began.

International reaction was mixed. The United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion as a violation of international law. Most Latin American governments criticized the action, while a few US allies remained silent or offered cautious support.

The operation was conducted without regional military support, though US forces cooperated with US diplomatic missions and intelligence assets on the ground in Panama prior to and during the invasion.

The Leaders of the US Invasion of Panama (1989)

On the US side, the key political and military figures were President George H. W. Bush, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Colin Powell, and General Maxwell Thurman, commander of US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM).

- George H. W. Bush authorized the invasion on the grounds of protecting US citizens, arresting Noriega, and restoring democracy in Panama.

- Dick Cheney managed the civilian-military coordination, ensured legal support, and maintained White House alignment with the Pentagon.

- General Colin Powell, applying the emerging Powell Doctrine, emphasized the use of overwhelming force and clear objectives.

- General Maxwell Thurman led the operational planning and execution of Just Cause. He had extensive experience in Latin America and directed detailed intelligence gathering months before the invasion.

In the field, command was exercised through the Joint Task Force South, reporting to SOUTHCOM. Lt. Gen. Carl W. Stiner directed tactical operations, including special forces coordination and ground combat units.

On the Panamanian side, Manuel Noriega, former head of military intelligence and Commander of the PDF, was the de facto head of state. Although technically not president, Noriega exercised executive control through military power.

Noriega controlled:

- PDF Chief of Staff Colonel Marcos Justines

- Chief of National Police Lieutenant Colonel Luis Córdoba

- A network of loyalists in intelligence, media, and Dignity Battalions

Noriega operated from heavily fortified positions, including La Comandancia and later the Vatican Embassy, where he claimed sanctuary under international law.

Guillermo Endara, the rightful president based on the May 1989 elections, was sworn in on 20 December 1989, in a US military base. He became the post-invasion political figurehead, although his authority was initially backed entirely by US troops and administrative support.

These leadership structures determined the rapid unfolding of the conflict, with Noriega’s isolation, US command efficiency, and tight operational control playing central roles in the outcome of the invasion.

Was There a Decisive Moment ?

The decisive moment of the US invasion came in the first 48 hours. The simultaneous airborne and special forces assaults disrupted the core of Noriega’s command structure, leaving his forces disorganized and demoralized.

The early morning of 20 December 1989, at 0100 local time, began with targeted strikes on key PDF facilities, including:

- La Comandancia (PDF headquarters)

- Torrijos-Tocumen International Airport

- Fort Amador

- Rio Hato Airfield

At Rio Hato, over 1,000 US Rangers parachuted in under heavy fire to secure the airfield and neutralize the PDF battalion there. At Fort Amador, Navy SEALs attempted to capture PDF boats and disable Noriega’s escape routes. One of the most intense firefights occurred around La Comandancia, where Noriega’s headquarters was nearly leveled.

In parallel, psychological operations included radio broadcasts and leaflet drops urging surrender. The Dignity Battalions, despite calls to resist, mostly disbanded or retreated.

By 22 December, Noriega’s capacity to command had collapsed. Remaining PDF units had surrendered or melted away. Noriega took refuge in the Apostolic Nunciature (Vatican Embassy).

During this time, US special forces surrounded the embassy and began a strategy of psychological pressure, including 24-hour loudspeaker broadcasts of rock music to break Noriega’s morale. The operation, known as “Operation Nifty Package”, aimed to force his surrender without violating diplomatic protocols.

Noriega surrendered on 3 January 1990, after almost two weeks of sanctuary. He was taken to Miami, where he faced charges of drug trafficking and racketeering.

This sequence — from initial strikes to Noriega’s capture — constituted the operation’s decisive phase. The rapid neutralization of command centers and airfields, combined with the failure of PDF units to regroup, meant that organized resistance ended within 72 hours. Noriega’s isolation and final surrender confirmed the total collapse of his regime.

Major Battles of the US Invasion of Panama (1989)

Several key battles defined the rapid execution of Operation Just Cause. Each engagement focused on disabling critical nodes of the Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF) and securing strategic infrastructure. The most significant battles took place in Panama City, Rio Hato, Fort Amador, Tocumen International Airport, and La Comandancia.

1. La Comandancia – Panama City

The PDF headquarters, known as La Comandancia, was one of the most heavily defended sites. US forces launched a coordinated air and ground attack during the opening hours of the invasion. The 82nd Airborne and Rangers faced intense small arms and RPG fire. The building was partially destroyed by AC-130 gunship support, which created firestorms that spread to adjacent neighborhoods. Civilian casualties were concentrated in this battle due to the urban density around the headquarters.

2. Rio Hato Airfield

This was the largest airborne operation of the conflict. Over 1,000 US Army Rangers conducted a low-altitude night parachute drop onto Rio Hato to capture the airfield and neutralize the 6th and 7th PDF Infantry Companies. Despite the element of surprise, the Rangers came under heavy resistance, with PDF troops using bunkers and surrounding buildings for defense. The airfield was secured after several hours of combat, with two US soldiers killed and over 30 PDF troops neutralized.

3. Fort Amador

Located at the Pacific entrance of the canal, Fort Amador housed PDF Marine units. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 4 attempted a night infiltration by boat to disable Noriega’s patrol craft and prevent his escape. The SEALs encountered stiff resistance, and four SEALs were killed. Despite casualties, they succeeded in destroying the boats, ensuring Noriega had no naval exit.

4. Torrijos–Tocumen International Airport

The 82nd Airborne Division deployed to secure the main international airport, critical for logistics and evacuation. The airfield was taken swiftly after limited resistance. Holding the airport allowed rapid insertion of additional troops and served as a forward logistics hub. PDF forces there offered minimal resistance and quickly surrendered.

5. Balboa and Colon

Operations in Balboa and Colon targeted PDF supply depots and communications centers. These areas saw sporadic firefights, but US forces used overwhelming strength to minimize prolonged engagements. PDF command and control in these regions collapsed within 24 hours.

6. Pacora River Bridge

SEAL Team 6 conducted an ambush at Pacora River Bridge to intercept a convoy of PDF reinforcements moving toward Panama City. The ambush destroyed several vehicles and led to the capture of a senior PDF officer, further accelerating PDF disintegration.

Overall, the tactical tempo, surprise, and air superiority of US forces overwhelmed PDF units. Combat lasted between four and ten days in various pockets, but no prolonged engagement occurred beyond 28 December 1989. US forces achieved control over major objectives quickly, allowing for political stabilization and the swearing-in of Guillermo Endara’s government. The brief duration and rapid sequencing of the major battles prevented PDF forces from regrouping or mounting effective counterattacks.

Was There a Turning Point ?

The turning point of the invasion occurred between 20 and 22 December 1989, when US forces neutralized the Panamanian Defense Forces’ ability to communicate, coordinate, and resist.

The destruction of La Comandancia removed the central command post. Simultaneously, the capture of Rio Hato Airfield prevented reinforcements from being mobilized from the southern provinces. The PDF’s strategic flexibility was broken by the loss of these two positions.

The surrender of Colonel Marcos Justines, Noriega’s Chief of Staff, on 22 December, further weakened morale and chain of command. Most PDF garrisons, facing isolation, began surrendering without coordinated resistance. US psychological operations, such as leaflet drops and controlled media broadcasts, encouraged surrender and demobilization.

The non-resistance of the population and collapse of the Dignity Battalions also shifted momentum irreversibly in favor of the US. Despite propaganda efforts, there was no significant civilian militia mobilization. Several units simply dissolved, and many of their members were later arrested or went into hiding.

A significant psychological shift also took place with Noriega’s flight to the Vatican Embassy on 24 December. It was interpreted domestically and internationally as an admission of defeat. Once Noriega was no longer issuing orders or communicating with his commanders, the PDF effectively ceased to function.

US control of Tocumen Airport and major roadways, along with round-the-clock air dominance, made it impossible for PDF units to move, resupply, or regroup. The short duration of the main combat phase ensured that no broader insurgency or long-term resistance emerged.

The turning point, therefore, was not a single battle but a synchronized breakdown of military infrastructure and leadership within the first 72 hours. From that point, the remainder of the operation shifted from combat to security stabilization and preparation for post-conflict governance under Endara’s administration.

Consequences of the US Invasion of Panama (1989)

The US invasion of Panama had immediate, mid-term, and long-term consequences for both countries. Militarily, it was seen as a successful application of rapid deployment doctrine, influencing future US interventions in Somalia, Iraq, and Kosovo. Politically, it led to criticism from international institutions and damaged US credibility in Latin America.

On the ground, the operation resulted in significant human and material losses. According to US sources, 23 American soldiers were killed and 324 wounded. Panamanian military casualties were estimated at around 200, while civilian deaths ranged from 200 to over 1,000, depending on the source. Human rights organizations reported extensive use of force in densely populated urban areas, particularly around El Chorrillo, where many civilian homes were destroyed during the assault on La Comandancia.

The Panamanian Defense Forces were dismantled by early January 1990. The US oversaw the establishment of a new national police force and disarmed all former military personnel. The Panamanian constitution was revised to ban any future standing army.

Guillermo Endara’s presidency began with full US support but faced legitimacy issues due to his installation under military occupation. Over time, he managed to consolidate control with assistance from US advisors. However, his term was marked by economic instability and social unrest, driven by inflation, high unemployment, and damage to national infrastructure.

Internationally, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion on 29 December 1989, calling it a violation of international law. The Organization of American States also issued a similar condemnation. Critics accused the US of violating Panamanian sovereignty and pursuing unilateral action without regional consultation.

Legally, Manuel Noriega was extradited to the United States, where he was tried and convicted on eight counts of drug trafficking, racketeering, and money laundering. He was sentenced to 40 years in prison, eventually serving terms in France and Panama until his death in 2017.

The invasion also contributed to debates over the Powell Doctrine and US military policy. It reinforced the preference for short, high-intensity interventions with limited long-term commitments. However, critics highlighted the civilian cost, the lack of international approval, and the strategic risks of acting without allied support or multilateral backing.

Operation Just Cause remains one of the few post-Vietnam military operations where objectives were met quickly, but the aftermath raised lasting questions about the use of force in US foreign policy.

Back to the Wars section