At the December summit, Paris, Berlin, and Madrid unblocked the SCAF: financing for the next phase, industrial sharing, and a commitment to a demonstrator in 2027.

In summary

After months of deadlock between Dassault Aviation and Airbus, French, German, and Spanish leaders took advantage of the European Council meeting on December 17-18, 2025, to reach a political compromise on SCAF, the “system of systems” program intended to replace Rafale and Eurofighter around 2040. The agreement seeks to secure the transition to the next phase by framing the governance, division of tasks, and principle of multi-year financing in order to preserve the objective of a demonstrator flight. The amounts remain to be finalized in budgets and contracts, but the order of magnitude is in the billions, following a phase 1B that is already underway. The test now begins: sticking to a tight schedule, dealing with an engine that is still maturing, and avoiding a return to disputes over intellectual property, exports, and technical leadership. This breakthrough reduces the risk of a shift to the British-Italian-Japanese competitor, without erasing the differences between partners.

The context of a program that has become a test of sovereignty

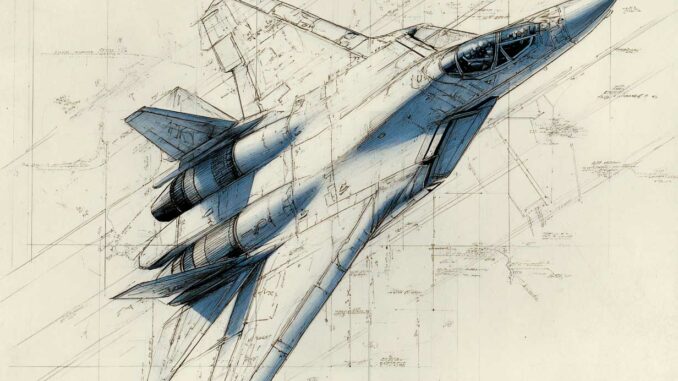

The SCAF, or Future Air Combat System, is often mistakenly summarized as “the future aircraft.” In reality, the ambition is broader: an interconnected system in which a new-generation fighter pilot and cooperates with drones, while relying on data networks, distributed sensors, and electronic warfare capabilities. It is a “system of systems,” and therefore a program in which the difficulty lies in interfaces, cybersecurity, software architectures, and the distribution of responsibilities.

This sprawling nature explains the repeated crises. Manufacturers are fighting less over a piece of metal than over decision-making power on critical components: mission software, data fusion, secure links, flight controls, stealth, and above all, access to know-how. Behind the press releases, the stakes are clear: who gets to hold the architect’s pen, and who ends up as a mere subcontractor.

In 2025, the deadlock has hardened. Several leaks and public statements have revealed a degree of mistrust that is rare for a program supposed to carry Europe’s defense. The European summit in mid-December did not “resolve” these antagonisms. Above all, it prevented immediate collapse by imposing a political framework where industrial negotiations were going round in circles.

The political agreement reached at the summit and what it really locks in

The heart of the compromise, as reported in government exchanges and commented on by the specialist press, is based on a simple logic: putting the state back at the center to force continuity. In concrete terms, the agreement seeks to protect phase 2 (the continuation of the demonstration work) by establishing a principle of shared financing, dated milestones, and a method of arbitration in the event of conflict.

The nuance is important. We are talking less about industrial reconciliation than about a political “safety net.” The aim is to make any further deadlock politically and financially costly. The three capitals have an immediate interest in this: to avoid the failure of a program estimated to cost around €100 billion by 2040, at a time when Europe’s credibility in defense matters is under scrutiny.

What the summit can really decide on are principles. For example: who is the prime contractor for a given pillar, what are the rules for sharing tasks, and what program governance is needed to prevent an intellectual property dispute from paralyzing the chain. What a summit cannot do is build trust between design offices. That is earned over years, through design reviews, tests, and accepted compromises.

Financing: solid orders of magnitude, but still fragile mechanics

Talking about a “financing agreement” requires precision. Some of the figures are already known, because they correspond to previous contractual phases.

A key milestone is the notification of a €3.2 billion contract for phase 1B, announced at the end of 2022 by manufacturers and governments. This phase covers research, technological maturation, and the overall design of the demonstrators. It does not finance the “final aircraft.” It finances risk reduction and the alignment of the pillars.

Subsequently, several previous public sources refer to a cumulative effort exceeding €8 billion to cover the trajectory up to the first flight of a demonstrator in 2027, adding up stages and work phases. But this is precisely where reality has become complicated: schedule slippages and governance conflicts have made these trajectories less credible and, above all, less legally “binding.”

For the next phase, the discussion generally revolves around a package worth several billion euros. Some analyses suggest a budget of around €5 billion for a more extensive demonstration phase, with flight tests, system integrations, and drone prototypes. The summit may agree on a principle: “let’s go ahead” and “let’s share.” The next step is to translate this principle into national budget lines, which are voted on and then signed into contracts. This is where the promise becomes vulnerable: a political crisis, budgetary arbitration, or industrial protests could still slow down the process.

In other words, the summit may open the door, but the program’s funding will depend on parliaments, programming laws, and the ability of manufacturers to deliver verifiable milestones.

Industrial distribution and the winners of the compromise

The central conflict remains the industrial distribution of the manned aircraft pillar, often referred to as NGF (New Generation Fighter). Dassault Aviation claims strong leadership in the name of integration, flight safety, and a specific French need (nuclear deterrence, aircraft carrier constraints). Airbus advocates for more balanced governance and more symmetrical access to technologies, in the name of sharing and “co-sovereignty.”

In a political compromise, “who wins” depends on what is written in black and white.

If the agreement confirms Dassault as the architect of the fighter jet, the French company will consolidate its position as the center of gravity. This is not just a question of industrial ego. It is the ability to define interfaces, and therefore to decide what is “open” or “closed” in terms of know-how. Conversely, if Airbus obtains strong guarantees on key sub-assemblies (structures, systems, integration of certain functions), Germany secures a tangible and politically marketable industrial return.

Spain, often underestimated in this tug-of-war, has a clear interest: to lock in its position on pillars such as sensors and connectivity architectures via Indra. In a system of systems, the cloud and sensors carry a lot of weight, both in terms of budget and power. If Madrid obtains consolidated co-responsibility for these building blocks, it will be a structural gain, even if the fighter jet remains the media symbol.

Incidentally, other players are benefiting from the fact that the program is continuing. The engine remains a highly sensitive duopoly (Safran and MTU). Missiles and effectors (MBDA) and electronics players (e.g., Thales, depending on the architectures chosen) need a stable schedule in order to invest. A program that “survives” is already a program that distributes workloads and retains skills in Europe.

The construction of the demonstrator and what “2027” really implies

A schedule promising a demonstrator flight in 2027 is an industrial gamble. A distinction must be made between what this demonstrator would be and what it would not be.

A credible NGF demonstrator is not an operational aircraft. It is a test platform. Its purpose is to validate flight control laws, aerodynamic architecture, stealth effects, basic sensor integration, thermal constraints, and the compatibility of certain real-time software. It can fly with “provisional” systems, test sensors, and safety standards specific to prototypes.

The sticking point, which is often underestimated, is the engine. French parliamentary proceedings have already highlighted a possible gap between the availability of the new demonstration engine and the aircraft demonstrator schedule, with the assumption of an interim engine derived (and improved) from an existing base while awaiting the final engine. This type of solution allows for earlier flight testing, but it reduces representativeness: thrust, fuel consumption, thermal integration, and infrared signature do not reflect the final aircraft.

Then there is the reality of industrializing a stealth prototype. Stealth is not a “magic coating.” It is a discipline of tolerances, joints, composite materials, panel alignment, and radar echo control. The slightest deviation from the chain results in rework. For a demonstrator, more imperfections are sometimes accepted. But we cannot afford to tinker: a prototype that flies poorly or breaks invalidates the entire political discourse.

Finally, there is software integration. The promises of “collaborative combat” rely on software and networks. However, these building blocks are the most frightening in terms of intellectual property and sovereignty. A summit compromise may impose a sharing method. It cannot magically accelerate the writing, qualification, and cybersecurity of complex architectures.

If 2027 is met, it will probably be with a realistic definition: a demonstrator focused on aerodynamics, flight safety, basic functions, and a gradual ramp-up of sensors and connectivity.

Political and industrial risks remain on the table

The December compromise does not eliminate the causes of the crisis. It puts them on hold, with the promise of an arbitration mechanism.

The first risk is political. The program depends on three countries, and therefore on three electoral calendars, three doctrines, and three budget priorities. The SCAF is designed for 2040. That is a long way off. However, defense decisions are now being made at the pace of the war in Ukraine, ammunition stocks, ground-to-air defenses, and short-term emergencies. A long-term program must constantly prove that it is not a source of income.

The second risk is industrial. As soon as we enter a more concrete phase, disputes become more costly. They affect the supply chain, tooling investments, and recruitment. Trade unions and industrial regions enter the debate. At this stage, a deadlock does not just “delay” things. It can destroy skills that cannot be rebuilt in six months.

The third risk is doctrinal. France wants a fighter jet capable of performing specific missions. Germany and Spain have other priorities. As long as these requirements are not stabilized, the specifications will change, and each change will reignite the debate over “who pays” and “who decides.”

The truth is that the summit agreement is not an end in itself. It is proof of life. Stability will be judged over a period of twelve to eighteen months, when contracts are signed, interfaces are finalized, and design reviews do not degenerate into endless lawsuits.

Competition from the British-Italian-Japanese program and time pressure

The direct competitor, in the European imagination, is the GCAP, led by the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan. This competition is twofold.

At the political level, it offers an alternative. If the SCAF appears ungovernable, some may be tempted to “jump on the bandwagon” or to continue purchasing American interim solutions for longer. The risk is then a two-speed Europe, with scattered sectors.

At the industrial level, competition shapes future exports. A new-generation fighter jet cannot survive without exports. However, exports impose rules on technology sharing and diplomatic compromises. If the SCAF fails to agree on export controls, it will condemn itself to a domestic market that is insufficient to offset R&D costs.

By “saving” the program, the December summit also sought to send a signal: continental Europe wants to go its own way and is not resigned to a US/Asia duopoly in the combat aviation of the future.

The next steps that will determine whether the revival is real

The credibility of the compromise will be measured by simple, almost administrative actions.

First, the transformation of the compromise into contracts: review schedules, technical milestones, and arbitration clauses. Next, the budgetary translation in each country. A program can be “priority” in discourse and underfunded in practice.

Third test: the ability to quickly deliver architectural choices. The combat cloud and Remote Carriers drones are often presented as the heart of the system. They will also be the area where software sovereignty and data security will be most contested.

Fourth test: the management of the engine and on-board energy. Sensors, links, jammers, and on-board computing require electrical power and controlled cooling. If we want a serious demonstrator, these constraints must be validated early on.

Finally, there is a less visible but decisive test: mutual acceptance of limitations. For SCAF to move forward, each country must agree not to control everything, and each manufacturer must agree not to own all the value. Until this maturity is achieved, the program will remain suspended at “last chance” summits.

The December 2025 summit may have averted an immediate accident. It did not eliminate the slope. The SCAF will only be credible when it becomes boring, in the best sense of the word: milestones met, disputes arbitrated, prototypes that roll, then fly, and an industrial chain that moves forward without quarterly crisis press conferences.

Sources

- Reuters, December 12, 2025, persistent deadlock and postponement to the December 17-19 summit.

- Reuters, December 16, 2025, governance disagreements and pessimism on the industrial side.

- Airbus (joint press release), December 16, 2022, notification of €3.2 billion contract for phase 1B.

- Senate (report “2040, the SCAF odyssey”), technical details on the engine and schedule.

- Aviation Week, July 10, 2024, discussion of funding ramp-up and phase 2.

- FlightGlobal, June 18, 2025, industrial tensions over phase 2 and demonstrator schedule.

- ECFR, December 1, 2025, political analysis of the causes of the deadlock and sovereignty issues.

- Financial Times, 2025, breakaway scenarios and alternatives being considered in Germany.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.