South Korea has unveiled an ambitious space roadmap with one goal: to build a base on the Moon and reach Mars by 2045.

South Korea has formalized a long-term space strategy that places the Moon at the heart of its ambitions. On July 17, 2025, during a public hearing in Daejeon, the Korea Aerospace Agency (KASA) presented a program structured around five priority areas, including low Earth orbit, microgravity missions, lunar exploration, and solar research. The goal is to develop an operational lunar base by 2045, following a series of intermediate steps: a robotic lander by 2032, followed by an advanced model by 2040. The agency is focusing on the development of clean technologies for descent, mobility, and in situ resource exploitation, particularly water ice. This plan is part of a global race to establish a presence on the Moon, with South Korea joining the United States, China, Russia, and India.

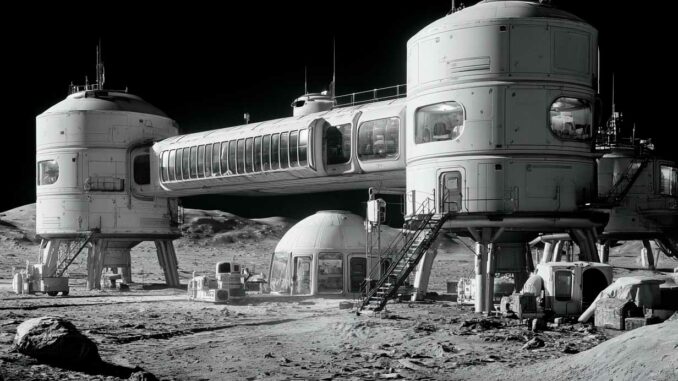

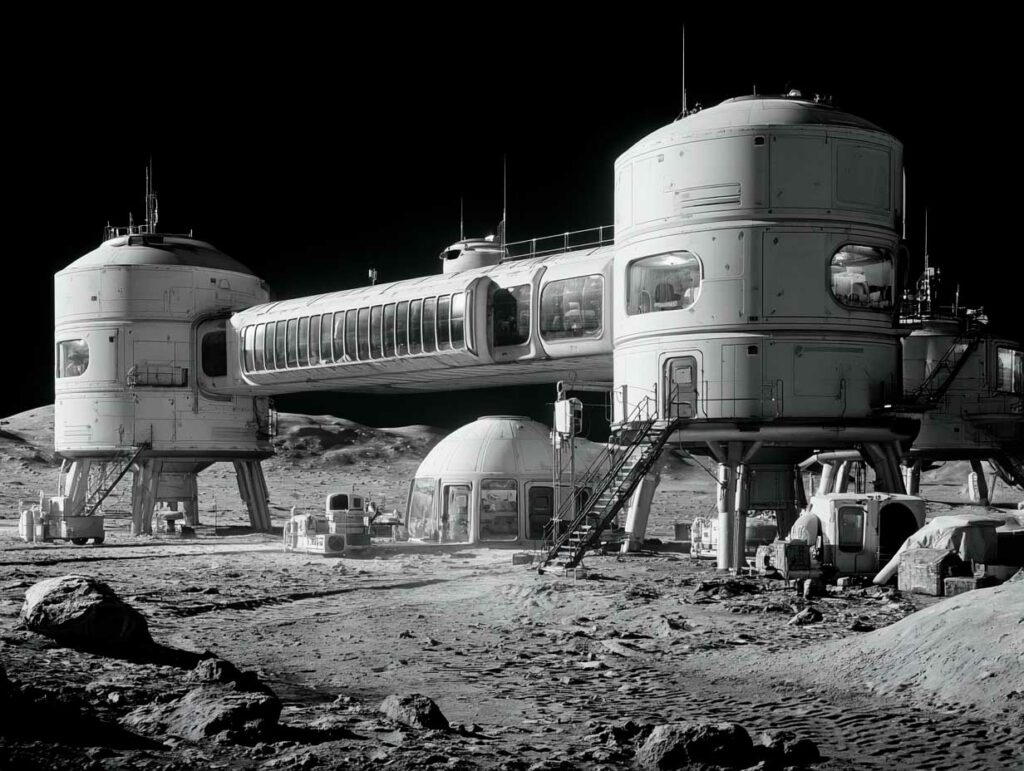

An ambitious roadmap to establish a sustainable presence on the Moon

The strategy unveiled by the Korea AeroSpace Administration (KASA) marks a major turning point for South Korea, which wants to move from emerging power to autonomous space player. The lunar base by 2045 project is structured in clearly defined technical, scientific, and industrial stages.

The plan includes:

- The development of a lunar lander by 2032, designed entirely in Korea,

- A more powerful version by 2040, capable of extended missions,

- The establishment of a life support system to accommodate equipment and, in the longer term, crews,

- The exploitation of lunar resources, particularly water ice, as a source of logistics and energy.

The extraction of water ice is a strategic point: once separated, it provides oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for propellants, enabling a circular economy on site. The Moon thus becomes a logistical relay point for distant missions, such as Mars.

The South Korean space program stands out for its progressive schedule, based on realistic milestones, some of which are already underway. In 2022, the Danuri (KPLO) satellite was successfully placed in lunar orbit. This satellite continues to collect data useful for mapping and characterizing landing sites.

With this roadmap, South Korea intends to break free from external dependencies by creating its own means of propulsion, autonomous navigation, and robotic operations. This autonomy is a matter of technological sovereignty, but also of strategic positioning in future lunar partnerships.

A young space agency supported by a thriving ecosystem

Created in 2023, the Korean Space Agency (KASA) inherits the expertise already present in institutions such as the Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) and the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM). This new structure centralizes exploration programs while strengthening coordination between research and industry.

The KIGAM, for example, recently conducted tests of prototype lunar vehicles in an abandoned mine, simulating low light conditions and difficult terrain. This type of experimentation paves the way for lunar mining operations and robotic exploration. Technology transfer is gradual, based on constrained terrestrial environments to refine sensors, robot autonomy, and software interfaces.

On the industrial front, South Korean companies such as Hanwha Aerospace, KAI (Korea Aerospace Industries), and Doosan Robotics are ramping up to supply critical subsystems, including cryogenic propulsion, mechatronics, and survival modules.

The government has allocated a space budget of nearly €650 million for 2025, with projected annual growth of 10%. This momentum places Korea in the top three in Asia, behind China and Japan, but with a strong emphasis on technological autonomy and the ability to export space solutions.

KASA also plans to create a national spaceport by 2030, probably on Jeju Island, in order to launch missions without relying on SpaceX or other foreign launch vehicles.

A lunar base as an economic, technological, and diplomatic lever

The lunar economic base by 2045 project is not solely aimed at scientific objectives. It is also an industrial and diplomatic gamble, aligned with the global strategies of the major space powers.

This base could be used to:

- Test construction technologies in extreme environments (3D regolith printing, inflatable structures, autonomous systems),

- Extract and transform lunar resources into consumables or semi-finished products (water, oxygen, aluminum),

- Ensure a permanent robotic or even human presence for maintenance and astronomical observation operations,

- Host biological experiments or laboratories protected from terrestrial disturbances.

From an economic standpoint, the Moon could become an energy production site, particularly through the transport of helium-3 or orbital solar stations. Although these hypotheses remain speculative, they are already attracting private investment funds.

On the diplomatic front, South Korea is seeking to negotiate its place in space consortiums. It has signed the Artemis Accords with the United States, but maintains a stance of independence, particularly in the face of Sino-Russian initiatives. This duality allows it to align itself with the rules of space law while developing a capacity for bilateral or regional action.

Finally, this lunar ambition is also a technological showcase for exports. Space is becoming a lever of soft power, on a par with energy infrastructure and telecommunications. A base on the Moon could eventually establish South Korea’s position as a supplier of components for international missions.

A lunar project linked to a long-term ambition for Mars

South Korea’s roadmap does not stop at the Moon. KASA aims to land on Mars by 2045. This project, still in its preliminary stages, requires a rapid upgrade of technologies such as orbital architecture, interplanetary propulsion, and heat shields.

This Martian ambition is not isolated: it is part of a global strategy to expand the national space reach, with several intermediate stages:

- Orbital missions to the Moon, then to asteroids,

- Development of highly efficient propulsion systems (plasma or electric),

- Mastery of precise landing on extraterrestrial soil,

- Creation of closed ecosystems for long-term survival.

The Mars project relies on the synergy between onboard sensors, advanced robotics, and onboard artificial intelligence algorithms. It also draws on a 20-year vision for the industrial fabric: nanomaterials, electronic reliability, and thermal endurance.

Mars exploration will also be a test of the political ability to maintain a technological course over several decades in an unstable geopolitical environment. South Korea will face competition from the United States, China, Europe, and new entrants such as the United Arab Emirates.

By linking its lunar program to interplanetary ambitions, KASA is seeking to build a complete exploration chain, from low orbit to the red planet. This strategy, although risky, could permanently reposition South Korea as a key player on the global space scene.

War Wings Daily is an independant magazine.