A detailed analysis of the First Intifada (1987–1993): causes, participants, leaders, clashes, turning points, and consequences.

The First Intifada began in December 1987 and lasted until the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. It was a large-scale uprising by Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip against Israeli military occupation. The movement was primarily driven by youth protests, civil disobedience, and grassroots mobilization, but later evolved into organized resistance by factions like Hamas and the PLO. The Israeli response involved military crackdowns, curfews, and administrative detentions. Over 1,000 Palestinians and around 200 Israelis were killed. It altered international perception of the conflict and led to the recognition of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) as a negotiating entity, setting the stage for the 1993 Oslo Accords.

What were the reasons for the First Intifada (1987–1993)

The causes of the First Intifada were rooted in two decades of Israeli military occupation following the 1967 Six-Day War, which left the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip under Israeli control. Palestinians lived under martial law, with restricted movement, land expropriations, home demolitions, and frequent arrests.

The demographic situation had also shifted. By 1987, over 1.5 million Palestinians lived in the occupied territories. The Israeli settler population had grown to more than 60,000 in the West Bank and Gaza, creating tension and resentment among locals.

Economically, Palestinians faced high unemployment, poor infrastructure, and limited access to resources, especially in agriculture and water. Many worked as day laborers in Israel under precarious conditions, with little job security.

A triggering event occurred on December 8, 1987, when an Israeli military vehicle collided with a car carrying four Palestinians in Gaza, killing them. Widespread belief spread that the collision was intentional, fueling riots.

Additionally, political marginalization and the lack of a sovereign Palestinian institution intensified anger. The PLO operated from exile, and local representation was limited. The influence of regional events, such as the Iran-Iraq War and the Lebanese Civil War, distracted international and Arab attention.

Grassroots organizations like student unions, local charities, and neighborhood committees had formed informal political infrastructure. These groups played a key role in organizing protests and disseminating information.

Religious factions also gained influence. The Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) was established in December 1987, as a spin-off from the Muslim Brotherhood. It criticized the secular PLO and called for armed resistance.

Thus, the Intifada emerged from accumulated social, economic, and political grievances, catalyzed by a specific incident, and organized through a mixture of secular and religious networks.

Who was involved in the First Intifada (1987–1993)

The First Intifada saw participation from multiple Palestinian groups, Israeli forces, and foreign actors. On the Palestinian side, youths, students, workers, women, and community organizations drove the early momentum.

The Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU) coordinated activities. This body comprised local representatives from major PLO factions: Fatah, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), and the Palestine Communist Party. The UNLU issued communiqués, organized strikes, and coordinated actions such as stone-throwing, boycotts, and demonstrations.

Another key group was Hamas, founded during the early weeks of the uprising. Hamas rejected cooperation with the PLO and called for Islamic liberation of all historic Palestine. It gained support through social welfare programs and religious messaging.

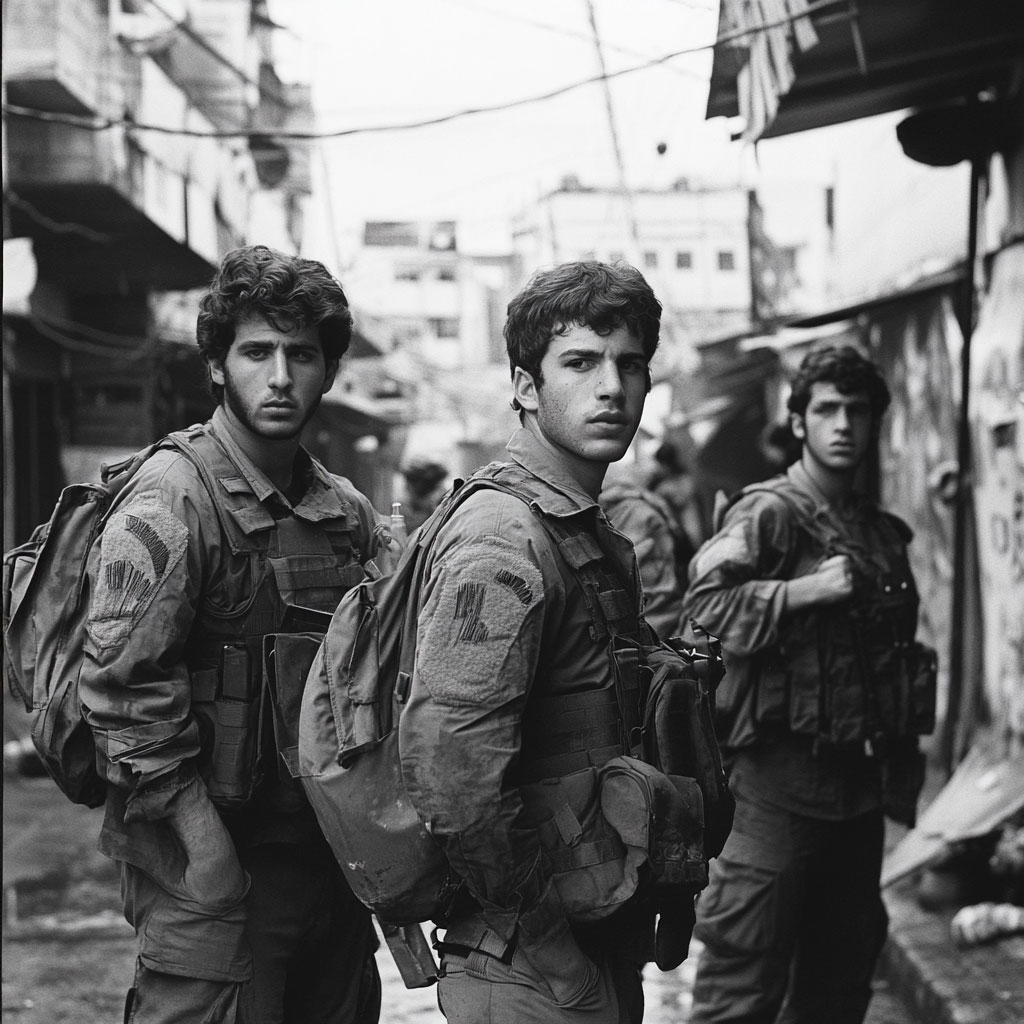

Israel deployed units from the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), Border Police, and Shin Bet (internal security). Their tactics included live ammunition, plastic bullets, tear gas, night raids, curfews, and administrative detention. Israel’s strategy was to suppress protests through overwhelming force and to detain suspected organizers.

Civil society actors were active on both sides. In Palestinian territories, local NGOs, hospitals, and religious institutions supported injured demonstrators and families of detainees. Israeli civil society also responded, with groups like B’Tselem documenting human rights violations and Yesh Gvul supporting soldiers who refused to serve in the territories.

The international community played a secondary role during the early stages. The United States, under Reagan and later Bush Sr., supported Israel diplomatically but pushed for moderation. The United Nations passed resolutions condemning violence and supporting Palestinian rights but lacked enforcement mechanisms.

The leaders of the First Intifada (1987–1993)

The Intifada did not have a single figurehead. It was decentralized, especially in its early stages. However, several key leaders influenced the direction and development of the uprising.

On the Palestinian side, the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU) provided strategic direction. Leaders in this group often remained anonymous to avoid Israeli arrest. Nevertheless, prominent figures within PLO factions guided policy and messaging from exile, notably Yasser Arafat, leader of Fatah and head of the PLO Executive Committee. While not physically present, Arafat used his position to influence tactics and negotiate with foreign entities.

Khalil al-Wazir (Abu Jihad), deputy to Arafat, played a significant role in coordinating with West Bank operatives. His assassination by Israeli commandos in Tunis in April 1988 dealt a blow to the organizational capability of the uprising.

Mahmoud Abbas, a senior PLO official, focused on diplomatic efforts and dialogue with foreign powers. His involvement laid groundwork for future negotiations.

On the Islamist side, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, founder of Hamas, emerged as the most influential religious leader. From Gaza, he articulated Hamas’s stance through sermons and pamphlets, emphasizing armed resistance and Islamic values. Yassin’s arrest in 1989 did not prevent Hamas from expanding its influence.

Inside the territories, local leaders such as Hanan Ashrawi, an academic and spokesperson, became internationally recognized voices. She acted as a bridge between Palestinian civil society and the global media. Faisal Husseini, based in East Jerusalem, was another key public figure engaged in diplomatic outreach and coordination with grassroots organizers.

On the Israeli side, Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin initially adopted a hardline policy aimed at suppressing the uprising through “force, might, and beatings.” Later, as Prime Minister, he shifted toward negotiation.

Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir maintained a security-first approach and resisted PLO recognition. Intelligence figures like Ami Ayalon (Shin Bet) and military commanders in the occupied territories had direct operational control.

Leadership during the Intifada operated through a mix of underground coordination, external political command, and visible public figures, reflecting the fragmented and multi-tiered nature of the uprising.

Was there a decisive moment?

The First Intifada lacked a single decisive battlefield event. Instead, its course was marked by strategic shifts, key assassinations, and political developments.

One of the most significant events was the assassination of Khalil al-Wazir (Abu Jihad) in April 1988. As the PLO’s military strategist, his killing disrupted coordination between external leadership and local cells.

Another moment was the King Hussein of Jordan’s decision in July 1988 to sever administrative ties with the West Bank, effectively recognizing the PLO as the political representative of Palestinians. This ended decades of Jordanian claims and gave new legitimacy to Palestinian nationalism.

In 1989, the Israeli government arrested hundreds of suspected organizers, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin and members of the UNLU. While these arrests disrupted momentum, they also elevated the status of imprisoned leaders.

A diplomatic shift occurred in November 1988, when the PLO formally recognized Israel’s right to exist and declared an independent Palestinian state. This changed international calculations and eventually opened dialogue with the United States.

In Israel, public opinion began to shift by 1991, especially after the Gulf War. Many Israelis questioned the sustainability of controlling millions of Palestinians under occupation.

The Madrid Conference in October 1991 was a diplomatic landmark. It brought Israeli, Palestinian, and other Arab representatives to the table under international sponsorship. Although inconclusive, it was the first formal peace conference.

While none of these were military victories, together they shaped the outcome. The combination of local resistance, international pressure, and internal Israeli debate gradually created space for political negotiations. These culminated in the Oslo backchannel talks in Norway, leading to the 1993 accords.

Thus, the decisive moments were cumulative shifts in diplomacy, regional politics, and public sentiment rather than a single turning point in combat.

Major battles of the First Intifada (1987–1993)

The First Intifada was not characterized by conventional battles but by continuous, decentralized clashes, often in urban environments. The intensity varied by region and period, with several key flashpoints.

In Gaza, Jabalia refugee camp became a focal point from the start. It was here on December 9, 1987, that the first mass protests erupted following the Gaza traffic incident. Over the next months, Israeli forces conducted daily raids and imposed long curfews, with demonstrators hurling stones and Molotov cocktails, and soldiers responding with live fire and arrests.

The West Bank city of Nablus witnessed some of the fiercest confrontations. Casbah neighborhoods, with their narrow alleys, enabled quick dispersal and regrouping of protestors. Israeli operations involved house-to-house searches, beatings, and detentions. The city became a center for UNLU operations.

In Hebron, settlers from Kiryat Arba were often involved in direct confrontations with Palestinian residents. The military frequently intervened to separate groups, but this created a constant cycle of protest and retaliation. The killing of Palestinian activist Hatem al-Silawi in 1988 triggered weeks of demonstrations.

East Jerusalem became an administrative and symbolic battleground. Clashes around the Damascus Gate and Salah al-Din Street occurred regularly. Israeli forces cracked down on demonstrations, fearing international attention due to Jerusalem’s contested status.

Ramallah, a major political hub, also saw extensive unrest. Students from Birzeit University played a key role. In January 1988, a major student-led march was violently dispersed, resulting in dozens injured and arrested.

In Bethlehem, street battles often erupted near the Church of the Nativity. The religious significance of the site increased international scrutiny, leading Israeli forces to employ more restraint.

Tactics evolved. Protestors began using burning tires, barricades, and coordinated general strikes. Israeli forces introduced plastic bullets, tear gas canisters, and collective punishments such as demolition of protestors’ homes.

By 1990, armed cells became more active, particularly Hamas-affiliated groups. Shootings of Israeli soldiers and settlers increased, prompting targeted killings and raids by Israeli units.

The death toll was uneven: by the end of the Intifada, over 1,000 Palestinians had been killed, compared to around 200 Israelis. Thousands more were injured or imprisoned.

There were no defined frontlines, but the daily confrontations in refugee camps, cities, and checkpoints constituted a prolonged urban conflict. The First Intifada introduced a new model of low-intensity conflict driven by civil resistance, urban warfare tactics, and psychological pressure on occupation forces.

Was there a turning point?

Yes. A major turning point occurred between 1990 and 1991, when both internal and external conditions shifted.

Internationally, the end of the Cold War and the Gulf War of 1991 redefined regional alignments. The PLO’s support for Saddam Hussein weakened its standing with Gulf states and the West. In contrast, Israel gained strategic value for the U.S. as a stabilizing partner.

Inside Israel, there was growing recognition that military suppression alone would not end the uprising. The human and economic costs, along with increasing criticism from global media and NGOs, created pressure for a new approach.

In 1991, the Madrid Peace Conference marked a clear break. For the first time, Palestinian representatives from the occupied territories negotiated openly with Israeli counterparts, under international observation. Although these delegates were not officially PLO members, they coordinated with the leadership in Tunis.

On the ground, the intensity of protests declined by 1992. Israeli security forces had detained or incapacitated hundreds of key organizers. Moreover, the rise of Hamas created intra-Palestinian tensions, leading to competing agendas.

A critical development was the opening of secret backchannel talks in Oslo, Norway, in early 1993. These negotiations involved senior PLO and Israeli officials. Unlike Madrid, they were informal and shielded from media attention.

By August 1993, a draft agreement had been reached. It was publicly announced on September 13, 1993, when Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat shook hands on the White House lawn. This marked the formal end of the First Intifada.

Thus, the turning point was not a single event but a series of political and military shifts that made continued confrontation less sustainable and negotiations more feasible. The Oslo process represented a strategic change rather than a tactical victory.

Consequences of the First Intifada (1987–1993)

The First Intifada had wide-reaching consequences for both Palestinians and Israelis, as well as for regional and global politics.

On the Palestinian side, the uprising revitalized national identity and created de facto political structures in the occupied territories. Committees formed during the Intifada became the nucleus for future self-governance.

The most significant outcome was the Oslo Accords of 1993, which led to the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA). The PA assumed partial administrative control over parts of the West Bank and Gaza. This was the first formal recognition of Palestinian political presence on the ground.

However, the accords also deepened internal divisions. Many viewed them as a compromise that failed to secure full sovereignty or resolve core issues such as settlements, Jerusalem, and the right of return.

For Israel, the Intifada exposed the limits of military control. The economic cost of occupation increased, with additional defense spending and a decline in tourism and foreign investment.

Public opinion within Israel shifted. While the right demanded tougher security measures, a growing segment of the center-left supported negotiation. This realignment helped bring Yitzhak Rabin back to power in 1992.

Internationally, the uprising reshaped perceptions of the conflict. Media coverage of child protestors, civilian casualties, and disproportionate force changed public discourse in Europe and the United States.

The Intifada also led to greater involvement from the United States, which played a central role in brokering the Oslo negotiations. The PLO, long seen as a terrorist organization, gained diplomatic recognition.

New players emerged. Hamas, born during the Intifada, became a permanent political and militant actor. Its refusal to accept Oslo created a dual power structure that still shapes Palestinian politics.

In education, civil society, and security, the legacy of the Intifada was institutionalized. Schools, youth centers, and municipal services formed part of the PA’s governance base.

The First Intifada did not resolve the conflict, but it transformed its framework. It shifted the Palestinian struggle from external exile movements to domestic political agency, and it forced Israel and international actors to recognize the conflict as a political issue requiring negotiated outcomes.

Back to the Wars section